Every new artiste wants to be known as an originator of their sound. In hindsight, this may veer towards eroding the history of those who may have pioneered the music genre known as Afrobeats.

By Emmanuel Okoro

As the world continues to witness the massive explosion of popular music from West Africa, known today as Afrobeats, there is a need to understand the nuances and contexts involved, especially with recent conversations bordering on the requisite fealty owed to the genre’s progenitors. This is even more pertinent today, given that some of the biggest names associated with the genre are now rejecting the ‘Afrobeats’ tag. Recently, one of Nigeria’s biggest musical exports, Wizkid, notably posted on his Instagram Story, sending shockwaves across social media: “I am not a f**king Afrobeats artiste! I am not Afro anything. And if you like Afrobeats, don’t download my album!”

Consequently, this has raised and reintroduced a myriad of issues associated with the term ‘Afrobeats’, its history, the appropriateness of this catch-all moniker, and the state of the West African music ecosystem today. Is the term ‘Afrobeats’ now a poisoned chalice for Nigeria’s music ecosystem?

What Really is Afrobeats?

In some quarters, the conversation about the genre and its origins can be traced to the early 2010s, when DJ Abrantee, in a bid to package West African music to the Western audience, used a catch-all phrase ‘Afrobeats’. Popular music at the time in regions like Nigeria and Ghana included Gyration, Kpangolo, Bakosó, Naija Hip-Hop, Galala, Bata, Konto, Ragga, Azonto, Apala, and Hip-Life, amongst others. Afrobeats, as it came to be, was launched into full effect, and was foisted on the popular music made. Over time, it has morphed into the major term for mainstream music in these parts.

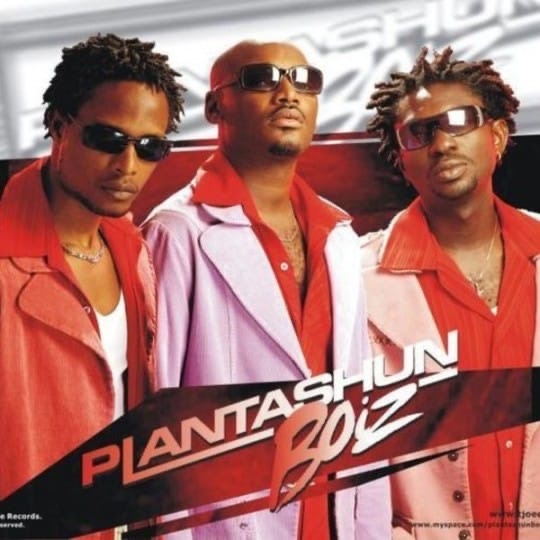

For proper educational and historical purposes, however, one may want to know how far back the origins of Afrobeats go. Can it be said that the music of the Lijadu Sisters, Onyeka Onwenu, and Chris Okotie carried tinges of what is now known as Afrobeats? A deep dive into the evolution of contemporary Nigerian popular music would show various eras marked by leading figures such as Junior and Pretty, The Remedies — comprised of Eedris Abdulkareem, Tony Tetuila, and Eddy Remedy — Plantashun Boiz which had 2Baba (formerly Tuface Idibia), Faze, and Black Face, are also known as pillars in the formation and evolution of Nigerian pop music known today as Afrobeats, as well as P-Square, D’banj, and Wande Coal. This generation led to the emergence of millennial pop stars in Wizkid, Davido, and Burna Boy, who undoubtedly gained fame within the period classified purely as Afrobeats.

Thus, does Afrobeats refer to the entire gamut of Nigerian pop music championed by the leading acts aforementioned and their various contemporaries? Does it take off from the DJ Abrantee 2010s era? These questions linger in the hearts of music and pop culture enthusiasts even as we try to grapple with the shenanigans of an ever-evolving industry and soundscape.

As will be seen going forward, today’s conversations hover around mainstream cultural proprietary claims, art form delineation, and the quest for honours due to industry veterans which largely stem from inadequate historical art structuring and documentation, and a culture of irreverence to process in general.

Given these extant conversations, this essay seeks to determine the necessity for this much-required structure and order, as well as an honour code to enshrine values of veneration for arguably Africa’s largest sonic industry and its veterans, for as the saying goes “He who does not regard where he comes from, will hardly go any far”. In other terms, does the subject of paving the way in Afrobeats matter as a collective when it doesn’t pointedly serve the individual interests of the artistes themselves as has been evidenced lately?

The State of Afrobeats Today

One of my cherished pastimes is mindlessly scrolling through Facebook and Instagram reels. Occasionally, I stumble upon distasteful red-pill content that disrupts my browsing, but more often than not, I discover captivating content creators whose work resonates with me. Just recently, while indulging in reels, I came across a surprising behind-the-scenes recording from superstar, Ayra Starr. It was a sneak peek into her preparation for a Honda Stage live performance. One statement from the video struck me, bringing my scrolling to a halt. “Growing up, I didn’t have an African, young, Black girl doing music at the same stage as other popstars making waves like this. I wanted to be that for people. This is my purpose; this is what I’m here to do.” While her statement looks profound at face level, it echoes sentiments from Nigeria’s younger generation of Afrobeats stars, which somewhat undermines or overlooks the contributions of those who paved the way for them.

Another noteworthy moment is Fireboy DML’s 2020 interview with Dazed, where he discussed his music’s departure from traditional labels like Afro-Pop or Afrobeats. He emphasised his focus on lyricism, stating, “My music focuses a lot on lyricism, and Afro music has not been popular for focusing on lyricism the way my music does.” The singer seemed to double down on his opinion, particularly in a recent BET interview, where he said, “The Afrobeats scene before I came in, it has always been beautiful. It was built on vibes and energy and percussion and instruments and everything. But I realised that there was something lacking, and that was pure soul and lyricism in our music. That was what I brought into the game. And I figured if you’re bringing something new to the table, it needs a name. That’s why I call it Afro-Life — it’s Afrobeats that has some depth to it.”

Interestingly, Fireboy’s stance isn’t isolated, as it somewhat draws a parallel to the African Giant himself, Burna Boy, who, during his interview last year with Apple Music’s Zane Lowe said, “90% of them [Nigerian artistes] have no real-life experiences, which is why most of [the] Nigerian music or African music or Afrobeats as people call it, is mostly about nothing, literally nothing. There is no substance to it — like, nobody is talking about anything in it. It is just a great time. It’s an amazing time.”

Fireboy is undoubtedly an incredible songwriter and lyricist; his albums, 2019’s Laughter, Tears & Goosebumps and 2020’s Apollo are undoubtedly critically acclaimed projects. However, his claims that Afrobeats lacked lyricism before his emergence in 2019 are misleading, as acts like Banky W, 2Baba, Sound Sultan, P-Square, Styl-Plus, and Wande Coal, are still revered today as legacy musicians because their music in the 2000s was bursting with layers of depth and complexities. For instance, 2Baba’s 2004 debut album, Face2Face, spurned gems like “Ole”, an ode of devotion and commitment; “Right Here” uniquely addresses reconciliation after a love gone sour, and of course, the evergreen “African Queen”, which needs no explanation. Wande Coal’s 2009 album, Mushin 2 Mo’Hits had tracks like “Taboo” and “Bananas” which treated the complexities of love. All of these tracks, amongst others, are laden with lyricism that rivals and, in some cases, thumps the music being made today.

Can it, however, be said that Fireboy is pointedly referring to the popular music made between 2011, when the Afrobeats tag was coined, down to his breakout in 2019? If that is the case, perhaps, there is a bit of merit to support his argument; some of the pop-driven music released during that era was barely intelligible or had no place for lyricism, or as Burna Boy puts it “has no substance”. Then again, what would we call artistes like 2Baba, Wande Coal, and Sound Sultan whose heydays predated that era?

Burna Boy’s music, for the most part, interpolates and samples works from Fela Anikulapo Kuti, who, as the pioneer of Afrobeat, is widely regarded as the forerunner of Afrobeats. Another argument can again be made particularly for his choice of ascribing his brand of music as Afro-Fusion. Around when the Afrobeats moniker was coined, Burna Boy, during an episode of The Juice, brandished his music as Afro-Fusion, and has notably maintained that stance ever since. So, while his comments on Afrobeats are incendiary, it would be a tad dishonest to conclude that the superstar is jumping on the bandwagon to branch off his music like the newer artistes do today. Afro-Fusion, as he has noted particularly during his appearance on The Daily Show With Trevor Noah, is a blend of Hip-Hop, R&B, Dancehall, and Soul, with the drums and percussions of Afrobeat at its base. And while talents before him such as Lagbaja, Shank, and Blackmagic can be said to have experimented with these fusions, Burna Boy is known to have properly tagged and popularised it.

For Ayra Starr’s claims, as much as the genre is a male-dominated sphere, there are a handful of women, throughout Nigerian music history, who have risen up to the ranks and operated at the summit of their careers. But the fact that there was (and still is) a handful of female superstars is indicative of the religious, moralistic, and conservative society which influences music consumption in these parts. The 2000s particularly had acts like Weird MC, Waje, and Muma Gee, who had their singles and features dominating the airwaves. However, some of these artistes were often subjected to intense scrutiny from the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), who were wont to ban any music or visuals projecting what was deemed indecent.

While the 2010s ushered superstars like Tiwa Savage, who is famously dubbed the Queen of Afrobeats, Yemi Alade, known as the New Mama Africa, and Goldie Harvey (of blessed memory) who broke the ceiling covering female artistic expressions, they were mostly pilloried by the NBC for “setting bad examples for girls”. Tiwa Savage, in particular, was public enemy number one after the release of the music video for her 2013 single, “Wanted”, as the visual portrayed her performing sensually-charged dance moves. The new wave of female Gen-Z artistes such as Ayra Starr, Bloody Civilian, Fave, Kold AF, and Qing Madi, who are choosing to not conform to societal norms through their music may, in a couple of years, introduce a generation of female artistes who will be inspired by them.

Perhaps, the reason for this deliberate (or indeliberate) erasure of older musicians is the unprecedented commercial success of the genre, fuelled by chart-topping achievements, sold-out global stages, collaboration with global superstars, cross-continental appeal, and the “Afrobeats to the World” movement. Never before has a West African genre been this massive, earmarked by the establishment of global music distribution companies in the region and joint ventures with local record labels. We must understand that Afrobeats has opened doors never thought possible before for our artistes, resulting in international success and establishing charts like the Billboard U.S Afrobeats Chart, and the Official Afrobeats Charts in the UK. Acts such as Burna Boy, who is Africa’s biggest superstar, have consistently sold out arenas, performed at the global stages, including the 2024 Grammys main event and UEFA Champions League final, and won a slew of international music awards. As a result, today’s artistes have reached levels of fame and fortune that their predecessors never realised.

However, this success now surprisingly comes at the cost of acknowledging and celebrating the foundations laid by those who came before, like 2Baba who was the first winner of the MTV EMA Best African Act Awards in 2005 and whose evergreen record “African Queen” was featured as a soundtrack on the 2006 American romcom, Phat Girlz; D’Banj featuring American rapper, Snoop Dogg on the remix of the 2011 single, “Mr Endowed” and, together with Don Jazzy, signed a record deal with Kanye West’s GOOD Music; P-Square teaming up Akon and Rick Ross for the chart-topping remixes of 2012’s “Chop My Money” and “Beautiful Onyinye” respectively; and 9ice whose 2008 hit record, “Gongo Aso”, gained so much popularity that the artiste performed it at Nelson Mandela’s 90th Birthday Tribute concert in London. All of these accomplishments, huge at the time, shouldn’t be eroded while spotlighting the rise of Afrobeats today.

Perhaps, another reason for this non-acknowledgement is an overinflated sense of self, and the inability to attribute parts of their sound, successes, or groundbreaking achievements to someone or a group of people. Every new artiste wants to be known as a pioneer and originator of their sound. In hindsight, this may veer towards eroding the history of those who may have pioneered the music genre now known as Afrobeats. Although musicians from these parts are under no obligation to brand their music as Afrobeats, especially if it doesn’t explicitly fall under its purview — one of the driving factors for this rationale being that foreign audiences, and in some cases, media, may be tempted to rope every music coming out of West Africa as Afrobeats. Thus, artistes, in a bid to distinguish themselves, may choose to raise their own banner. I am particularly worried that these individual actions might endanger and shunt the progress of the ‘Afrobeats to the World’ movement as a collective.

This trend of distancing one’s self from traditional Afrobeats labels extends to artistes like Rema and CKay, who tag their music as Afro-Rave and Emo-Afrobeats. As a result, this phenomenon of ascribing different tags to “Afro-” music has, over time, devolved to audiences hilariously stamping different genres, such as Afro-Cultism, Afro-Depression, Afro-Civil Servants, Afro-Incantations, Afro-Trenches, and Yahoo-Piano, to different musicians.

What Does Paving the Way mean?

Paving the way, especially within Afrobeats, is often viewed under the lens of older or established artistes and label executives signing and mentoring emerging talents who turn out to be successful. For example, a personality like Don Jazzy, who is often credited for being instrumental in the careers of stars like D’Banj, Rema, Ayra Starr, Wande Coal, Tiwa Savage, and Reekado Banks would be said to have paved the way for them. As such, artistes without mentors like Don Jazzy, Olamide, or Mr Eazi, may be sceptical of the notion of someone paving the way for them. Is this idea unfounded? Not so much. The Nigerian music industry, beyond platforms like Project Fame, The Voice Nigeria, and Nigerian Idol, isn’t properly structured for up-and-coming acts to “blow up”. Most of the superstars and sensations today have had to struggle from the ground up, with little to no support or backing from record labels. For instance, a recent TTYA Podcast revealed that Burna Boy’s mom used most of her finances to insure an American tour for the artiste because intended sponsors like Live Nation wouldn’t take the risk to do so, as he was relatively unknown. The stiff cost of commercial success and critical acclaim these artistes enjoy comes from personal sacrifices to write, record, produce, distribute, and push their music individually until the world began to listen. A notion, such as someone else paving the way for them, may be offensive to even admit out loud.

Paving the way can be also viewed through the lens of older artistes co-signing newer acts, known colloquially as “putting people on”. This can include collaborations during their early career stages, inviting them to perform at their headline concerts, and introducing them to their large fan bases, both online and offline. A prime example of this is Davido, who frequently promotes the importance of support with his favourite quote, “We rise by lifting others”, and has actively supported musicians signed or unsigned to his DMW label.

But importantly, paving the way should be viewed as embarking on strategic moves that will further, down the line, make it easier for others to succeed. Going by its literal definition, paving the way means facilitating the entrance for; leading the way for someone or something. Thus, it is safe to assume that in this case, an artiste (or group of artistes) “paving the way” is one whose successes create opportunities and solutions that previously did not exist.

Rema acknowledged this during his acceptance speech after winning the Best Afrobeats Award for his global hit record, “Calm Down” at the 2023 MTV VMAs. Despite branding his music as Afro-Rave, the singer delivered props to Afrobeats trailblazers, saying, “Shoutout to the people who opened the doors for me. Big shoutout to Fela who started Afrobeat in the first place. 2Baba, Don Jazzy, D’Banj, D Prince, Runtown, Timaya, Wizkid, Burna Boy, Davido. And I want to give a huge shoutout to the new generation of Afrobeats. We are here to take it to the rest of the world.”

It is crucial for the younger generation of Afrobeats talents to recognise the hard work, influence, and contributions of those who came before. Ignoring the contributions of older musicians would be disingenuous and detrimental to the future of Nigerian music – as more of these acts grant interviews to global platforms to advance their cause. Now, more than ever before, it is important to have proper documentation in place in order to give Afrobeats the branding or, in this case, the rebranding befitting of it. We cannot continue to allow our music, much like the name of our country, to be appellated and run on terms dictated by external factors, as this will, further down the line create the problems the industry is facing today.

It is also vital, too, for the music industry, in partnership with governmental agencies and boards like the National Council for Arts and Culture, and the Centre for Black and African Arts and Culture, to promote and properly establish platforms like the Afrobeats Hall of Fame (ABHF), where audiences and artistes themselves can learn about the trailblazers and industry stakeholders who have advanced its cause over the years.

Else, in twenty years, we may witness a new crop of artistes, who will completely disregard the giant strides of these current acts. But what do I know? I’m just a guy who mindlessly scrolls through Facebook and Instagram reels, and I’m Afro-tired.

Emmanuel ‘Waziri’ Okoro is a content writer and journo with an insatiable knack for music and pop culture. When he’s not writing, you will find him arguing why Arsenal FC is the best football club in the multiverse. Connect with him on X, Instagram, and Threads: @BughiLorde.