Unruly excels because it can find colour through sparkling production and honeyed vocalists, but it lags, expectedly, where these do not live up to the billing in certain songs.

By Patrick Ezema

As Nigerian rapper, Olamide, ramped up to the release of his new album, Unruly, he gave a preview via Twitter (now X) for what was in store. There, he warned in advance to expect “bo pata” music – a euphemism for sexually explicit content – so that those who are averse to sexual impropriety would stay away. But there was something about this term that offered more insight than its literal meaning, his use of the crude street slang, “bo pata,” coupled with the album’s chosen name, proffered a rough setting for Unruly. The album would be Olamide’s return to the slang-spitting music of his early career. But this is only in part, as he would also soak in the sexual, if not romantic, essence of his more recent materials. This new album looked to place somewhere between Olamide’s street classic project, the 2012 YBNL, and the lovestruck UY Scuti album from 2021. But as Unruly was released, we realise that the album is not so much an average of the artiste at the extremes of his discography, but an aggregation of it, including that of his 2020 AfroPop-coloured soundscape, Carpe Diem.

If this really is his last studio album as Olamide claims – even as we would be naive to hold artistes to their word on such matters – it makes excellent sense that his farewell can take in a little from every corner of his artistry. Fourteen years in mainstream music have seen him evolve, sometimes in slow turns, other times with sharp bends, to arrive at the man he is today. On Unruly, Olamide makes an effort to shake off the rust and return to the old days, but the muse for this musical style — starting life the hard way in the slums — is now nothing more than a bad memory for him, a remnant of a former life.

On some tracks, his rap deliveries feel like a poor recollection of his past. “Street Jam,” for example, begins with the line, “This is for the streets,” making no secret of his intention to roll back the years. This is an unneeded prologue in the song, with the monosyllabic response (yuh!) to every line, easily calling to mind his catchy street classics like the 2017 song, “Wo!!” But “Street Jam” possesses none of the jovial vibe or delivery variations across lines in “Wo!!” Even the chorus comes off as monotonous. “Hardcore,” another street-directed track, also suffers from this inflexibility; it seems Olamide forgets his most successful rap songs came from making songs for popular appeal rather than merely rapping to unflavoured low-tempo Hip-Hop beats.

(Read also – “Africa Unite” Review: Reggae Meets Afrobeats on Bob Marley’s Reimagined LP)

Thankfully, the monotony of these tracks is the exception and not the rule, so when the street-pop offerings come on Unruly, they are more likely to be accompanied by sonic elements that enhance their palatability. Olamide is adept at this, if not from his days in getting the Nigerian audience to dance to street music, then from his days guiding his YBNL-signed artiste, Asake, to achieve the same.

The album shines in its incorporation of various sounds and elements to spice it up, and even more, in how Olamide can achieve diversity across the album whilst still remaining cohesive. First, he achieves this by retaining a single producer across the bulk of the album, and Eskeez (the producer) takes on the challenge as he did producing UY Scuti. Eskeez produced “Street Jam” and “Hardcore,” but with the other songs he worked on, he is more generous with the sonic elements.

Playful keys highlight Olamide’s delivery across the album, contrasting and balancing his gruff vocals. “Jinja” flirts with Amapiano production while “New Religion” embraces it in totality. On “Gaza,” a crowd backup vocals accompany Olamide at each turn. It is a better version of call-and-response than “Street Jam.” In “No Worries,” the crowd joins Olamide to trustingly commit his future to God who has brought him thus far.

These sonic elements could easily be fixtures in Asake’s musicality, so while there are ongoing conversations about Olamide’s influence on the artistry of his protégé, Unruly should also spark discussions about how that relationship can go both ways,

although some of Olamide’s sonic experimentations are well beyond Asake’s purview. We see such in the similar-sounding tracks “Gaza” and “Doom” where Olamide not only flexes his range on two disparaging genres but also melds them so closely that a switch in both is not easily noticeable. The former is reminiscent of Olamide’s show-stealing verse on the street-pop singer, Portable’s “Zazoo Zehh.” On “Gaza,” Olamide recalls humbler times, “Before the money we stack/ Dem tell us ‘make we pack’/ Now, they all wanna come back.”

(Read also: The Sarz Academy Garners an “A” For Effort on Memories That Last Forever 2)

On “Doom,” Olamide sneaks in a message to his fair-weather friends who only hover in the time of plenty, “Pussy ass niggas tell me what’s up/ Don’t try to kill my vibe.” It may be a witty comment but his intentions here are chiefly carnal. He waxes his lyrics with both subtle and explicit lewd lines, none of which can be quoted here. Suffices to say his earlier warning was for good reason.

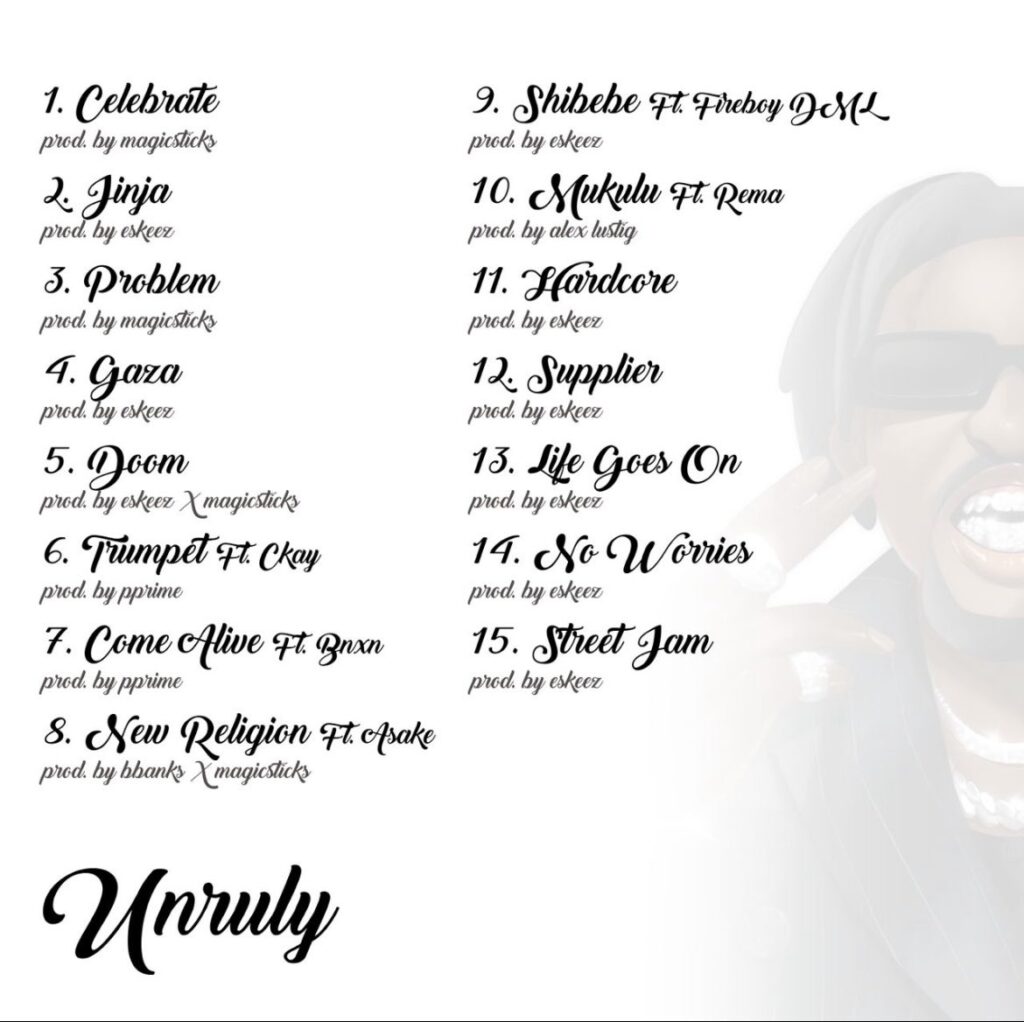

Unruly is demarcated into three equal parts; the first and last laps draw heavily from street music, but in the middle, where he crams in all his five features, is where he properly becomes a romantic. He recruits an enviable selection of Afro-Pop vocalists, a kind that can only be assembled by an artiste with enough high standing in the music industry. CKay, BNXN, Fireboy, and Rema sit side-by-side at the centre of the album, with Asake, sitting comfortably in their midst.

His guest artistes, however, do not symbolise consistency. BNXN’s chorus on “Come Alive” is monochromatic, even as this track is chock full of the cleverest sexual innuendoes in the album, with lines such as “E no be water wey fit to quench the fire wey dey burn inside her/ She thirsty.” Fireboy’s contribution to “Shibebe” has little redeeming quality. Olamide has spoken about the challenge both artistes experienced in trying to find sonic balance in the studio. “Shibebe” suffers as Fireboy is pulled too far out of his element that he cannot craft his characteristic brilliant melodies.

On these featured songs, Olamide lets the guest artistes set the pace with the chorus before settling into verses. By so doing, his performances are either limited or enhanced by these artistes. CKay and Rema fare better, especially the latter who crushes on “Mukulu.” “My baby no reach my baby, dey play,” he opens, before oohing and ahhing his way into the sexual essence of the track. Of course, no one shares a significant chemistry with Olamide than Asake, and it is telling as their track sits at the centre of the project. They usher in “New Religion” under their joint reign. Producer, Magicsticks, is brilliant behind the boards, providing log drums, a saxophone, and a violin in turn, as Asake and his mentor take turns underlining just how special they are —”I get the magic, abracadabra”

Magicsticks’ production elements also make an appearance on the album opener, “Celebrate,” one of three of the producer’s contributions to Unruly. Here, Olamide is grateful for the triumphs in his career, and the song showcases his intention to bring refinement to his street-pop essence. It is a sprinkle of glitter to the gritty feel of Olamide’s rapping.

Unruly excels because it can find colour through sparkling production and honeyed vocalists, but it lags, expectedly, where these do not live up to the billing in certain songs. Most of all, Olamide’s dynamism is the album’s guiding light, so although Unruly is his most street-focused album in recent years, it is a celebration of Olamide’s evolution, rather than a reversal of his legacy.

Lyricism – 1.6

Tracklisting – 1.3

Sound Engineering – 1.5

Vocalisation – 1.4

Listening Experience – 1.6

Rating 7.4/10

Patrick Ezema is a music and culture journalist. Send him links to your favourite Nigerian songs @EzemaPatrick.