The cultural identity that Bongo music wears makes it distinct and, indeed, delightful, but it may also be its greatest albatross in the march to international visibility…

By Chimezie Chika

A City and its Music

Owerri is the city of enjoyment, the city of sin, of passion and recklessness, the Las Vegas of the Igbo heartland, or at least that is what it seems to be in the general view. In the confines of the city, in its clustered streets and throbbing avenues, in its showiness, there is the determination to take the consummation of life to its most passionate extremities. As you drive or walk through its streets, its clubs, its many hotels, you hear — not surprisingly, for all such cities possess an inner music — a beat. It may seem rather too brazen at first, if you recognise it, but this is the free character of a city in possession of a heart. Some say its debauchery and the tendency to take life less seriously; others say it’s Bongo.

(Read also: Umu Obiligbo and the Igbo Music of Life)

Bongo is not a person, though, as you will find out. It is not a fashion trend or an invisible man-about-town catching the sensuous imagination of a city. Bongo is, simply put, the music of a people — the kind of music that has become the embodiment of a people’s values — and their own expression of their worldly outlook. “It is our music,” Chigozie Opara, a friend and Owerri native, tells me. “You won’t hear it anywhere else.” Bongo is to Owerri what Calypso is to the Caribbean islands or Jazz to New Orleans.

In an article on music and the modern city experience, published in Urban History, Markian Prokopovych projects music as an integral part of a city’s planning, development, and the acquisition of a distinct atmosphere or “feel.” He talks of the instances and future of “lifeless” cities where music and entertainment is absent. There are especially instances where whole images of entire cities are crafted out of musical history. The modern urban experience, he argues, is not only about infrastructure and economy but also about music which, in itself, also contributes to the infrastructure and economy of modern urban clusters.

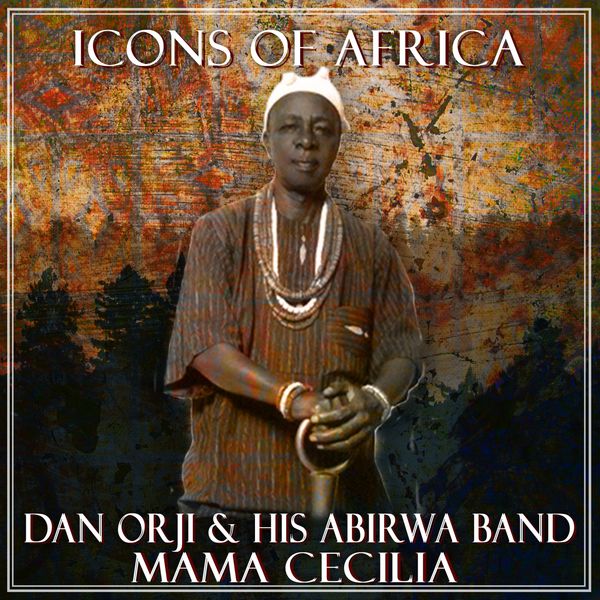

Owerri came into its own when Bongo music began to take root in the 1950s. Prior to that, Owerri had been a small town long beneath the shadow of its colonial past, under the autocratic rule of the early District Commissioner, H.M. Douglas, whose legend prevailed for many years. In the late 1950s, Nze Dan Orji started playing music in open streets while still in his teens. The Ghanaian Highlife of E.T. Mensah, and his cohorts, was still permeating the crannies of Nigeria, and musicians were taking creative liberties with the new sound. In Igboland, each tribe added their own cultural and tribal influence to the music. The result is the splintering of distinct sub-genres of Highlife.

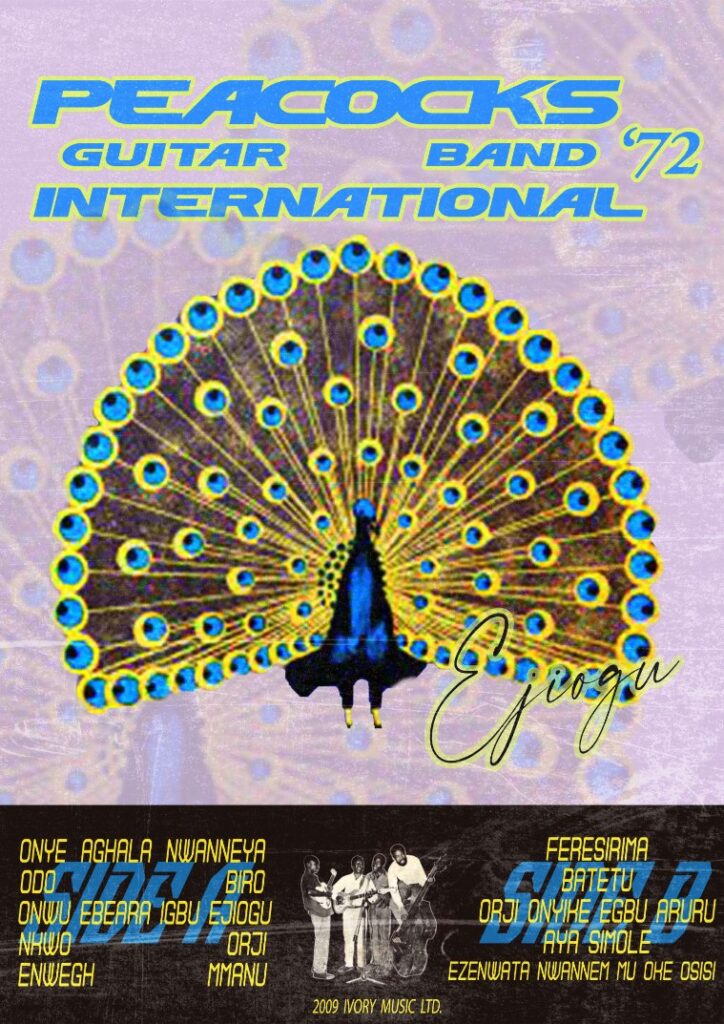

It is not very clear when the distinct drum-based form of Highlife being produced in Owerri acquired the name Bongo, but during the 1960s, when Nze Dan Orji started releasing singles, it was clear there was something different in his interpretation of typical Highlife sounds: he was expressing the language and the life of his own people. Highlife itself is a highly flexible hybrid sound — a malleable mix of influences across cultures — which appeared at just the right time, during an audacious movement for political autonomy across Africa. The Nigeria Civil War — as it did everything else in Igboland between the 1967 and 1970 — halted the further development of the music. In 1972, Nze Dan Orji, and Raphael Amarabem formed the Peacocks International Band. The band’s first single, “Sambola Mama,” was the first truly popular Bongo music. It would go on to sell 150,000 copies in Ghana, and more than double that amount in Nigeria. The 1970s and ‘80s marked the strongest periods in the trajectory of Bongo music. It was during this period that it seemed to exhibit truly global aspirations. Of course, during that selfsame period, Highlife music in West Africa – with the likes of Celestine Ukwu, Cardinal Rex Lawson, Victor Uwaifo, Ebenezer Obey, Osita Osadebey – was in its golden age.

(Read also: Celestine Ukwu’s Musical Philosophy: Is This the Sweet Spot of Highlife?)

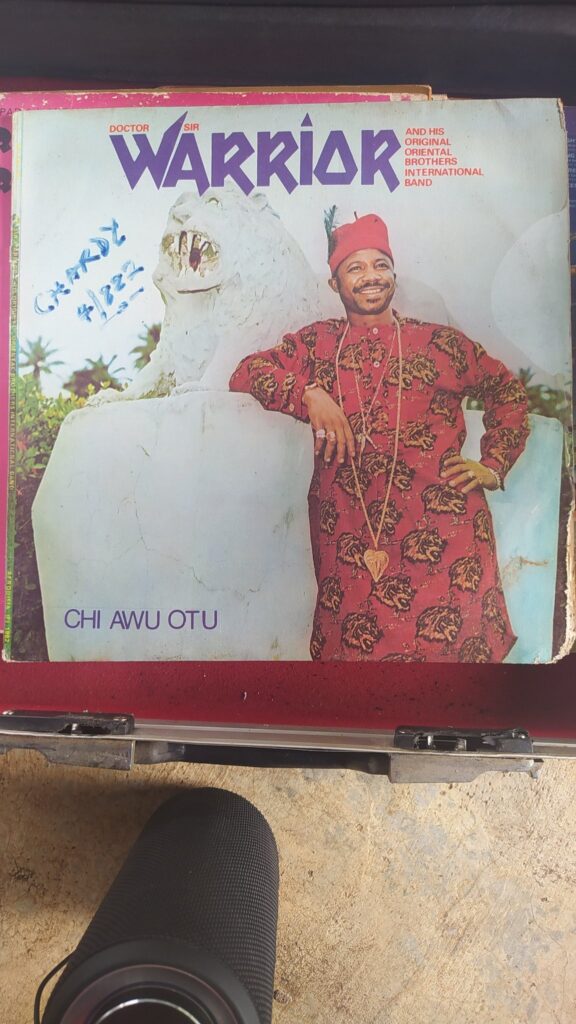

By far the group that popularised the Owerri brand of highlife were the Oriental Brothers International Band. Beginning in the late ‘70s, this is the group that truly changed the game. Centering the lead vocalist, Dr Sir Warrior, they took Bongo music to a level that has never been attained since. Oriental Brothers brought a more universal outlook to the music, with advanced guitar work (marked by the introduction of the pedal guitar), which is often the mark of the highly accomplished Highlife of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

“Oriental Brothers are the best ever,” Kenechukwu Ibedu, a music executive and filmmaker, tells me. “What they did is amazing.” Recently, Ibedu and his brother, at the behest of Palenque Records in Colombia, are helping to revive the Oriental Brothers Band, through its surviving members, Dan Satch Opara, and Aquila Opara.

Bongo and its Meta-musical Aspirations

My first encounter with Bongo music was in 2008. It was my first time in Owerri, and my uncle was taking us, my twin brother and I, to get registered at a catholic boarding school in the city for our first year senior secondary. We moved between markets and the school, buying things on the prospectus. Most times my uncle played Bongo music on the car stereo. “Do you know Bongo music?” he’d ask. “It’s the best thing about Owerri people.” I remember those times now with the tempo and sounds of the assured voice of Bogar Bongo singing “Give me my spoon that I may eat with others” in Owerre-Igbo. I was fascinated by the somewhat new turn of phrases that were markedly different from the type of Igbo I had known all my life up until that point.

Perhaps the greatest feature of Bongo music is its use of the Owerri dialect. Probably the most sonorous Igbo dialect, Owerre-Igbo has a slight comedic lilt to it and gives the music its most significant identity. Another is its emphasis on drums, especially wooden traditional drums. Unlike other subgenres of Igbo Highlife, its aspirations are simple: to exalt the good life and talk about its flattering and less flattering moments. In the Bongo philosophy, there is the concept of story, camaraderie, and hospitality, these being subsumed in the Owerre saying, “Ba’ama n’ime uyo. Uyo wu uyo mu a gi.” (Come into the house. The house is for me and you.)

On the streets, we often heard songs from twin duo band, Chimuanya and Chinedum. My memories of Owerri in the late 2000s are filled with the sounds and lyrics of their songs: “Onye Eze,” “Oge Chi,” and “Ayakata Bongo.” Other popular singers include Saro Wiwa, Chuks Mbata (Bogar Bongo), Ababanna, and Sunny Bobo, whose debut album, Sunny Bobo, has always been popular. ND Stanley Nnorom’s “Arabanko” has also continued to dominate Owerri and the rest of Igboland since its release in 2011.

Bongo music holds a certain romantic allure for Igbo speakers, not only in the sensuousness of the language but in the rhythm of its rendition. The music, perhaps more than any other external culture, has the unmistakable influence of Congolese Soukous music, notable in its flamboyant use of the conga (bongo) drum percussion. Its sounds are jaunty, fast, and danceable. The influence is notable for its political significance, since Eastern Nigeria and Southern Cameroons were once administered as one territory. Efik culture also has an input in the music.

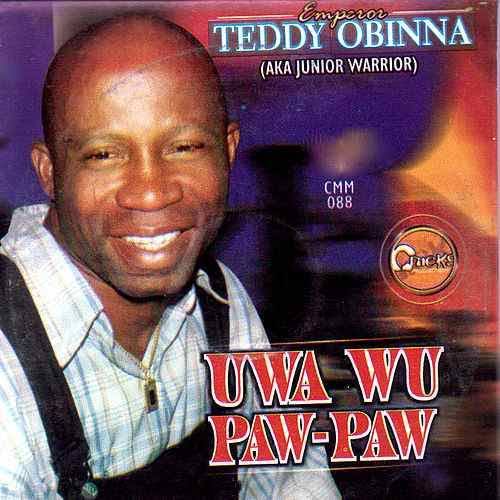

Bongo music expresses no temporal ideal. It is rooted in the moment, that is, in the holistic experience of the present. It exalts the way we live now, but like all Igbo music, it is also filled with proverbs, idioms, and nuggets, though not in a style-changing way. Bongo music is by no means brooding even when it talks of grave things. It has a tendency to use nonsensical bombast and vocal percussions to complement the rhythm of the music. The aliases of its musicians also exhibit this, sometimes bordering on the hyperbolic: “Chief Dr Sir Warrior,” “Bogar Bongo,” “Emperor Teddy,” “Sunny Bobo,” and others.

(Read also: Storyteller and Gentleman: What is the Measure of Mike Ejeagha’s Influence on Highlife Music in Nigeria?)

Bongo Music and the Issue of Identity

While other sub-genres of Igbo Highlife music are more democratic in their reach and active practice, Bongo is almost exclusively the preserve of Owerri people. This is mainly attributed to its inseparability from the Owerri dialect and the Owerri experience. The music projects a cultural singularity that is different from all other forms of the Igbo Highlife, not especially in its subject matter, but its character or, if you will, its identity.

Not many singers outside Owerri and its environs can even attempt to practise the music. The dialectic flair will always be absent if the singer is not privy to the Owerri experience as a bona fide native. Here, then, is the issue, the core of the problem stunting the globalisation of the music. The music seems to have attained its greatest moments in decades past, yet the new productions coming out are also persistently vibrant with new talents and voices. The cultural identity that Bongo music wears makes it distinct and, indeed, delightful, but it may also be its greatest albatross in the march to international visibility.

In 2014, Emperor Teddy Obinna released his very popular album, Uwa wu Paw Paw, somewhat in the tradition of Sir Warrior, with greater dominance of guitar work than drums. Perhaps this is an indication of things to come, yet one wonders if his style truly reflects the “Bongo Spirit” since it is a little more subdued. I do not particularly believe that music must shed its most significant influence in order to appeal to a global audience. What any given genre of music needs is to find its moment in history and take it. Such a moment might occur during major political or social overhauls. On that note, the coming years will be even more telling for the future of the genre. And until then, we will continue to luxuriate in the joy of Bongo music.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1