Empathy is the mark of great artistes and Lawson’s artistry was not lacking in this. It was present in the adroit instrumentals of his best songs, and in the raw emotions audible in his vocals.

By Chimezie Chika

Erekosima or He Who Shall Not Be Named

The story goes that in Buguma, within the thousand rivers of the Niger Delta, a father named his son “Erekosima”, which translates to “he who shall not be named”— a name that cleverly circumvents the very art of naming. The father believed that this particular son could possibly not stay long in this world, because he had previously lost three sons in infancy. Perhaps on the basis of the son’s untimely death at 32 along the Warri-Sapele road on 16 January 1971, who is to say he did not prove his father right?

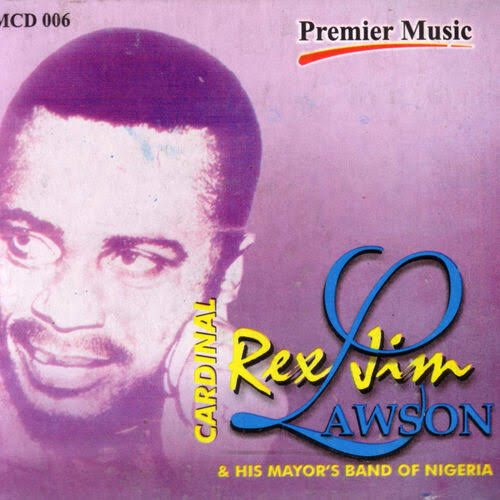

The son we speak of here is none other than Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson (“Rex”, being a clipping of “Erekosima”), one of Nigeria’s legendary Highlife musicians. Whatever his father’s fears had been when he cried his way out into the world on March 4, 1938, as a soft bundle of flesh and umbilicus, Lawson’s name has blazed through the generations, like a lighthouse on a rocky promontory. So much for he who shall not be named.

(Read also – An Ode to Classics: Unearthing the Treasures of Old Nigerian Music)

Good Fortune

If Lawson’s good fortune was to not die in infancy, he made exceptional use of his short-lived life. As a restless young man growing up between his father’s Kalabari people in Buguma, Rivers State, and his mother’s Igbo people in Owerri, Imo State, Lawson went into music as an adolescent member of a church band in his paternal hometown. He was also involved in the Christ Army School band, Buguma, where he learnt to play the trumpet and met his friend and music partner, Sunny Brown, whose skilled trumpeting accompanied much of Lawson’s music in later years. By his late teens, he was working with Sammy Obot (of the Broadway Dance Band fame) in Lagos. The older musician helped him master the trumpet — an instrument that will become a distinct signature of his musical style.

Lawson spoke six languages, including Efik, Izon, Kalabari, Igbo, and Akan. His knowledge of some Ghanaian Akan languages came during the period when he toured the country with Obot and other Nigerian trumpeters who were highly coveted in the Highlife scene in Ghana at the time. The real foundations of his linguistic inclinations could be traced back to him being a product of inter-ethnic marriage: Kalabari and Igbo. Perhaps that, too, is a stroke of good fortune, for it enriched his musical range in a way no other musician was able to replicate at this peak period for Highlife music.

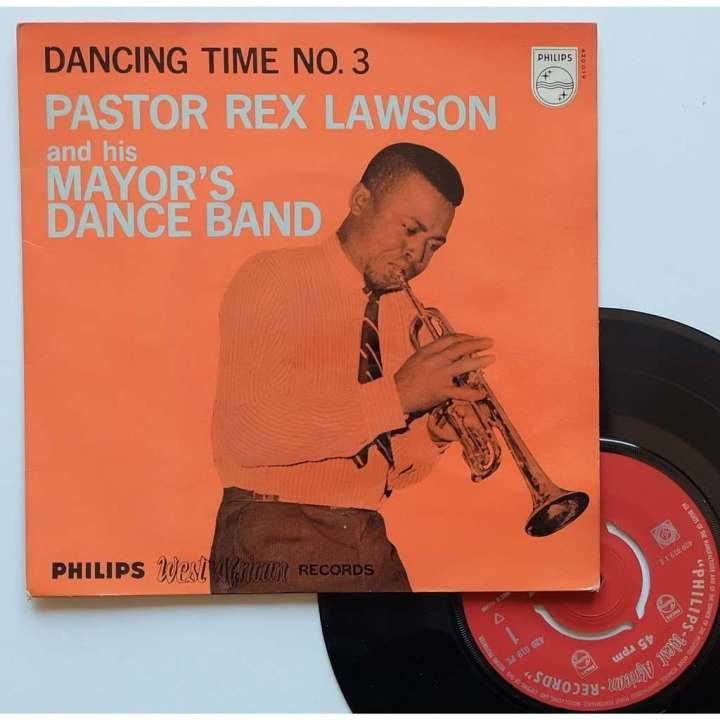

Between 1958 and early 1960, Lawson spent time in the bands of Bobby Benson, Chris Ajilo, and Victor Olaiya — these being the most prominent Highlife musicians of the 50s and early 60s. He began to release his own music in 1961 when he formed his own band, the Mayor’s Band of Nigeria. The members of the band included Sunny Brown, trumpeter; Tony Odili, who played the conga; and Ralph Amarabem (later of the Peacocks Guitar Band International), who played the guitar.

In the period between 1961 and 1967, he released over a hundred songs, making him the most prolific Highlife musician in the 1960s. As his popularity grew, Lawson became highly sought-after in events and social circles all over Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon and Chad. Radio stations played his music, and his songs were constantly on the airwaves. On many occasions, he was invited to perform live in the studios of Radio Lagos. In this whirlwind period, there was no rest for Lawson. He was always on the road and seemed to only have time for music and music-related activities. Yet he loved it: the adrenaline of being on stage, and the passionate involvement that each song drew from him. Known to be of an exceptionally gregarious temperament, he made friends effortlessly wherever he went — a quality which, again, can be ascribed to the ease with which he learnt new languages. As he sang in “Ibi Na Bo”, it was all part of his good fortune from the Creator.

Jolly Papa, and Lawson’s Emotive Musicality

“Jolly Papa”, one of Lawson’s earliest songs, is a classic slow-burning track with an enduring message of goodwill and friendship. Its inspiration is said to have been the ship, SS Apapa, which used to sail regularly between Lagos, Accra, and England in the early twentieth century. Partly rendered in a Ghanaian Akan dialect, it is also claimed in some quarters that the song is a remix of an earlier song by Ghanaian musician, K Gyasi. “Jolly Papa” is the song that most captures Lawson’s convivial attitude to life. His singing here has a poignant effect, the searing passion of a man who paid attention to the world around him.

Lawson’s life was music and he saw no other way to live; he is known to shed tears during performances. According to Sir Maliki Showman, a legendary saxophonist, Lawson chose music over money whenever the choice presented itself — a testament to the depth of value he placed on music. For Lawson, his music came to him from the heavens (as he revealed in “Nume Inye”) and so it was impossible to exist without it. Halfway through Lawson’s discography, one notices a tendency towards the ecclesiastical. Again and again, he calls to God, to the heavens, and to Ijaw deities. In a private interview on Voice of America (VOA), he revealed that his sobriquet, “Cardinal”, came from his fans who thought it fitted the religious overtones of his music.

Shadowing the religious mood that permeates Lawson’s music is a philosophical focus on the reality of survival in a troubled world. This aspect of his music is extraordinarily world-wise and rich in Kalabari and Ijaw idioms. Repeatedly, through his music, he ties this existential peril to the timely intervention of a higher power (in the form of God, deities, or influential individuals). Each song expresses a variation of this theme. In the melancholy “So Bo Ibibi Na”, he calls out to powerful beings and people for help, revealing that “a troublesome person ought not to fight in his hometown”. It should be said that the mood of the music in this mode is usually melancholy. In “Bere Bote”, a beautiful folk song rendered in the Nembe-Ijaw and Kalabari languages, the voice beckons on the community to listen, for there is trouble. And on it goes on.

(Read also: What is Bongo’s True Identity?)

Other parts of Lawson’s music evoke the jauntiness and jollity of urban social life in ‘60s Nigeria, or the impetuousness of virile youth. The exceptionally lively and talkative Lawson comes to life in tracks like “Yellow Sisi”, “Love Mu Adure”, and “Sawale”. In these songs, the polyglot Lawson is at his most linguistically versatile and lewd. The tender love song, “Love Mu Adure”, which he sang in Igbo with distinct Bongo rhythms, talks about admiration for an Owerri woman named Adure; “Yellow Sisi” and “Sawale” are romantic ditties with Congolese influences in their rhythms. While no Highlife musician touches King Sunny Ade (and of course the Victor Olaiya of “Mo Fe Mu Yan”) in riding a euphoria of sexual innuendo and risqué banter, Lawson’s crooning about love, heartbreak, and sex is by no means inferior in that regard.

“Tom Kiri Site”, unarguably the most fully realised song of Lawson’s career, is a masterclass in beat and rhythm. At its centre is a virtuosic groove of instrumentals — the heady call-and-response between drums and trumpets — that couch its lyrics about the need for the urgent intervention of God in a world that has gone crazy. “Tom Kiri Site” is the product of a musician fully conscious of his considerable talents.

The Nigerian Civil War and Lawson’s Allegiances

At the height of Lawson’s fame, Nigeria suddenly descended into chaos, caused primarily by two military coup d’etat that came within the first six months of 1966. The aftermath saw the Igbo and the other ethnic groups from the old Eastern Region caught in a pogrom that led to the secession of the region as the independent Republic of Biafra. By July 1967, the Nigerian Civil War began.

Lawson was deeply moved by the events that led to the war. He was touched by the Igbo pogrom through his mother, and he was even more touched by the existential threat that the events posed to his minority Kalabari people. In the early days of the war, he was fully involved with Biafra and continued to sing and release songs, most of which were panegyrics in honour of military elites. “Hail Biafra”, released shortly after the declaration of Biafra, praised Odumegwu Ojukwu, the Biafran leader, for making Biafra a reality, asking God to help him lead the war.

As the war progressed, Lawson’s early enthusiasm began to dissipate as he observed his Kalabari people and other ethnic minorities being forcibly mistreated in wartime Biafra. He rejected the notion of Biafra completely and began to identify with Ijaw nationalist movements, such as those led by Isaac Adaka Boro. By mid-1968, the Nigerian Army repossessed large swathes of the Niger Delta in resounding defeats of the retreating Biafran Army. Lawson recorded two songs afterwards with his renamed band, the Rivers Men. The first, “Major Boro”, is a tribute to the Ijaw national hero who had died in mysterious circumstances. In the chorus, he asks: “What took your life? You liberator of the people?” The second, “Gowon Special”, again praised General Yakubu Gowon, the Nigerian Head of State at the time, for liberating the minorities of the Rivers. Opening with continuous trumpeting that pays tribute to martial music, the song is onomatopoeic and uses repetition to emphasise the joy of liberation: “Pakaye eh? Gowon o’ bote” (What has happened? Gowon has come/ The man of the people, has he not come?). Lawson was not in Nigeria when the war ended; he had left for London during the war’s last stages in 1969, where he recorded his last album, Rex Lawson in London.

(Read also – Celestine Ukwu’s Musical Philosophy: Is this the Sweet Spot of Highlife?)

Respect the Wealthy, Don’t Disdain the Poor

If there was anything to glean from the events of the war, it was that Lawson was a man who believed in wealthy, powerful people and beings; but he also believed in the rights of the poor and powerless. Empathy is the mark of great artistes and Lawson’s artistry was not lacking in this. It was present in the adroit instrumentals of his best songs, and in the raw emotions audible in his vocals. “So Ala Temen”, perhaps his most popular song in the posthumous era, has a strong emotional effect and passes a deeply philosophical message: “So ala temen” – God made the rich/“Ori piki igoin temen” – He also made the lowly/“Ala wolo ma, igoin derima” – Respect the wealthy, don’t disdain the poor. The inimitable rhythms of “So Ala Temen” have been relentlessly copied by later gospel and Highlife musicians in Nigeria.

Lawson saw music as a universal language, the language of passion and immediacy. His great facility with languages — his fleet-tongued style of vocal engagement — gave his music a cosmopolitan feel. This might be the reason why his music has remained influential in the past half-century since his death. Nigerian Highlife musician Orlando Owoh remixed his “Yellow Sisi” in a title of the same name. Ghanaian-Nigerian artiste Alex Zito remixed “Sawale” in his 1991 reggae song, “Baby Walakolombo.” Afrobeats artiste and producer Larry Gaga remixed “Love Mu Adure” in his 2019 song, “Iworiwo” ft 2Baba. The most popular remix of a Rex Lawson song is Highlife musician Flavour Nabania’s remix of “Salawe” in his 2005 hit, “Nwa Baby (Ashawo)”. In short, Lawson seems to be present in all crannies of Nigerian music today, whatever form it takes.

So, then, there is nothing to do but to listen: to the chorale salvos of the trumpets and saxophones, to the dominant thumping of Odili’s conga drums, to Amarabem’s masterly guitar strings. So let us listen to this soothing music, full of great feeling; there is a heart to it — the very substance of it evokes love for life and a visceral awareness of what it means to be vibrant and alive in the world. The originator is not here with us, but we are alive to savour this lyrical abundance.

What else is left for the living but the memories and songs of a great man who has sallied forth into the realm of the dead? And so we shall sing that song today, aware that so ala temen, aware too, that ori piki igoin temen. The message of the unnamable man is clear: Respect the wealthy, don’t disdain the poor. Respect the music, too, respect the dead. So it is, now, tomorrow, and forever.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Republic, The Shallow Tales Review, Iskanchi Mag, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Efiko Magazine, Brittle Paper, and Afrocritik. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1

Rex Lawson would be grateful for this piece written on him and the depth of his music, and the effort to identify the periods of his life.

I am a big fan of Rex Lawson. Few years ago, to mark my birthday, I took a hired taxi to Abonnema, to his family house, to pay tribute to his memory. I had there for a couple of hours, soaking up the environment. It was the least I could do then.

I intend to learn the Ijaw language so I can fully understand the philosophy of his music and more.