Folklore rules the mythical landscape of Mike Ejeagha’s music; his lyrical calibrations are more about the prosody of folksongs and folktales; his language of the music is Igbo, and the purpose is didactic…

By Chimezie Chika

Ejeagha, Storyteller

Akuko Mike Ejeagha. Mike Ejeagha’s story. This was the Igbo phrase that trailed any indication that a person was telling tall tales (or long tales, as the case may be). In that moment of recognition, the person being told the tall tale would say, “I na-akoakuko Mike Ejeagha” (You are telling Mike Ejeagha’s kind of story). But the real Mike Ejeagha’s tales were not lies; they were mostly long-winded morality stories infused into the veins of his music to make a point. Using this technique, the singer, Mike Ejeagha, popularly identified with the prefixed sobriquet, “Gentleman,” built a legend that has gradually transitioned into common idioms in every day interactions. Akuko Mike Ejeagha. Mike Ejeagha’s story. This piece is not a tall tale — though it is Mike Ejeagaha’s story in a more literal sense — but what manner of influence would a singer have to make his musical technique widely identifiable and become part of modern Igbo idioms?

(Read also: Umu Obiligbo and the Igbo Music of Life)

Born in 1930 at Imezi Owa in Ezeagu Local Government Area in Enugu, Mike Ejeagha, grew up in Coal Camp in the city of Enugu. His mother was an accomplished folk dancer and singer. After basic education, he started his musical career in the late 1940s, but it was not until the 1960s that people began to the notice his guitar-rendered folksongs. Growing up in Coal Camp, he had come into close contact with the street music of the time. Coal Camp in those days was a perfect location to indulge his interests. There were many characters: the families of miners, low- and mid-level civil servants, petty traders and people who had just arrived from the rural hinterlands. Observing the musicians and musical groups that performed in the streets of Coal Camp, what fascinated Ejeagha was the rhythm of the changes between the long percussions of the ekwe and ogene instruments, and bawdy lyrics interspersed in the beat. He was interested in the interplay of rhythm and words, the enthralling technique of stringing heady rhythms, of making music.

In particular, Ejeagha followed two musicians who also lived in the same compound with him in Coal Camp. There was Moses “Moscow” Aduba, who was from Onitsha, and Cyprian Uzochiawa from Oye. These men played at public bars and events in the 1940s and 1950s. Ejeagha visited them at home and watched them practice; later he began to take guitar lessons from them. In 1950, he started his own band, Mike Ejeagha and the Merry-Makers, and began to play his music all over Eastern Nigeria. The same year, he auditioned with Atu Ona, who was the Controller of the Nigerian Broadcasting Service in Enugu, and was given a radio programme known then as Guitar Playtime. He performed at different venues throughout the 1950s, producing music that was usually well-received, though not widely known. Towards the end of the fifties, he played in a music group called Paradise Rhythm Orchestra. It was an eclectic affair, often accommodating new, transient musicians who would tarry for a while and then move on to better things. Their performance venues were hotels, and they copied Ghanaian highlife. Amidst these activities, Ejeagha listened to the songs of Victor Uwaifo and Ebenezer Obey and was impressed with the melody they created using their own indigenous language.

His breakthrough came in 1960 when he released his first hit, “Ofu Nwa Anaaa.” The song was based on folklore and was the beginning of a shift in aesthetics for Ejeagha. It was the same year of Nigeria’s independence. Increasingly popular in the 1960s, he formed a bigger band, Premier Dance Band. He would disband the group at the start of the Civil War. There was shock, chaos, and trauma everywhere in Biafra in the early months of the war — a general struggle for survival and self-preservation — and people didn’t seem interested in music. As the determination and grit of active fighting progressed, he started a new radio programme, called Igbo Play. When the Biafran capital, Enugu, fell and the seat of government moved to Umuahia, Ejeagha, now without the leverage of a sedentary radio station, began to go around playing for soldiers. In 1974, four years after the war, he formed a new band, Gentleman Mike Ejeagha and His Trio.

Ejeagha, Gentleman

Kedu ihem mere mmadu jikpuru m n’ onu (What did I do to deserve being called out always?)

Kedu ihe mere mmadu jikpuru m n’onu (What did I do to deserve being called out always?)

Obu mu bumbuna-enweroikwu (Am I the first not to have relatives?)

Obu mu bumbuna-enweroibe (Am I the first not to have kinsmen?)

Anya m ka one ka one (Is my eyes not the same as others?)

Ogbenyedibumbuadi (The poor have always existed)

This is from the song, “Onye Ori Utaba” (The Snuff Thief). Akuko n’ egwu Mike Ejeagha. The story according to Mike Ejeagha’s music. Another common saying. Oh, and the context of usage changes here. I might discredit the story you just told me as fiction, more valuable for its moral content than for its uncertain realism. Ah, akuko n’ egwu Mike Ejeagha! Mike Ejeagha’s style, Akukona Egwu (storytelling in music), is part of the artistic structure of the Igbo music, an affirmation of the technique of the ancient storyteller, moving seamlessly between music and narrative. The title, “Gentleman,” came from what people recognised as the gentle, reassuring nature of his music, and its propagation of cultural values.

Folklore rules the mythical landscape of Mike Ejeagha’s music; his lyrical calibrations are more about the prosody of folksongs and folktales; his language of the music is Igbo, and the purpose is didactic. Having learnt to play the guitar when he was barely twenty, Ejeagha’s first act was to establish his difference. According to him, he put his personal feelings into the stringing of his guitar, not unlike the tocadores of the Spanish Andalucía. Ejeagha pioneered a distinct style, inimitable and captivating. There is usually a mythical bent in his music, as if the listener has suddenly turned a corner into an improbable world, distant, animalistic, and yet familiar — something similar to folktales and legends — with the complement of proverbs, idioms, and ancient speech rhythms.

Ejeagha engaged in rigorous research as a folklorist. In his prime, he travelled across Igboland colleting folktales and songs. At present, he has over three hundred recordings in the National Archives. “Nna mu gwara mu,” (my father told me) — a recourse to the wisdom of the elders — often appears as a refrain in his songs, showing what his music is all about. Ejeagha’s belief is in the profound effect of moral counsel in human society. Society would fall apart if we do not learn from our experiences. In folklore sits the repository of human experiences from ancient times.

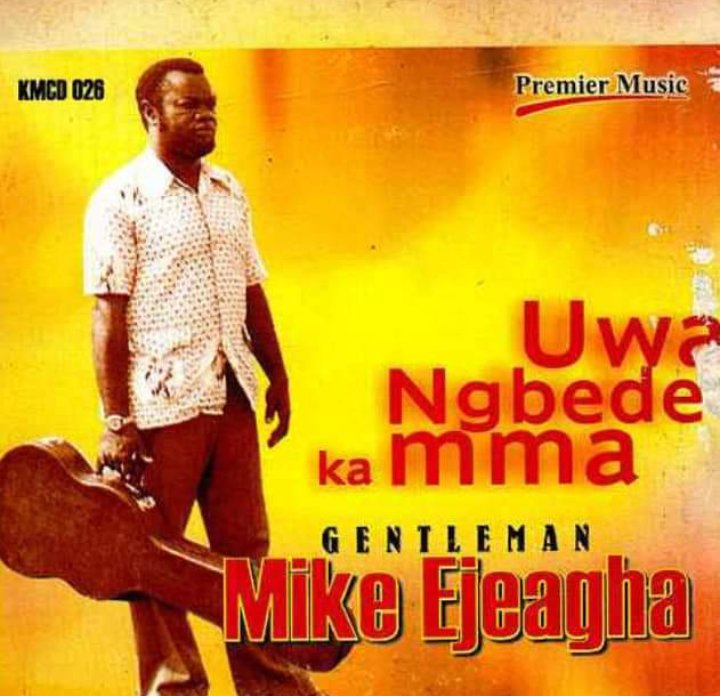

All his best songs are a combination of folk storytelling, prosody and the natural rhythm of proverbs and idioms. “Onye Ori Utaba” tells the story of the lamentation of a poor thief. “Omekagu” tells the story of a king and his two sons and the result of his poor treatment of the eldest. There are also songs like “Onye Ndidi N’Eli Azu Ukpoo,” “Welu Nwaya Sobe Uwa,” and “Uwa Mgbede Ka Mma,” which all extol the virtues of patience. Beyond the story, Ejeagha elevates music as power a powerful utility, the idea that music is not for its own sake but must do or say something about life.

(Read also: Celestine Ukwu’s Musical Philisophy: Is this the Sweet Spot of Highlife Music?)

Ejeagha, a Pioneer’s Fate

Akuko n’egwu Mike Ejeagha. The music never ends without a moral lesson, a final coda. Here however, in this story, there is no moral lesson. The interest is on Mike Ejeagha’s influence as the pioneer of a Highlife genre. What are his legacies? Why do we still play and luxuriate in his music today? One answer is our instant connection to our roots as a people, our indivisibility from the culture we originate from. In homes and in traditional events, Ejeagha’s music is a common staple. That, in itself is enough. Let the music be judged mainly by its relevance to the people it originated from, and nothing else. On the questions of aesthetics, the opinions of people might differ, especially based on their knowledge of Igbo folklore.

While Ejeagha’s influence endures in bits and pieces, his music is not easy to copy. This uniqueness may have contributed to the decline of his music in the mainstream. There are still many people who do not believe that the man who has so enriched the Igbo language is still alive. A few years ago, Igbo folk performer and poet, Amarachi Attamah, and Charles Ogbu, a social influencer, brought to the attention of the public the decrepit conditions in which Mike Ejeagha was living. Through the efforts of Attamah and Ogbu, a public rallying call was made and Ejeagha’s house and compound was renovated, culminating in the visit of the governor of Enugu State. In his nineties, Ejeagha’s life and music awakened the many who recognised his important place in the history of Igbo Highlife. The goodwill he has enjoyed in his old age came from this recognition.

Gentleman Mike Ejeagha produced 33 albums in a career spanning over sixty years. There’s not much to add to that except to state that he is, without doubt, the grandfather of modern Igbo folk music. All this is the story according to Mike Ejeagha’s music. Akuko n’ egwu Mike Ejeagha.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.