Chibundu Onuzo’s “The Spider King’s Daughter” takes the form of didacticism that midwifed the Onitsha Market Literature in Nigeria…

By Nzube Nlebedim

A few months after reading Chibundu Onuzo’s Welcome to Lagos, I read The Spider King’s Daughter. The novel, the author’s first book, won the Betty Trask award. It was also shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize. After reading Welcome to Lagos, I did a short review of the book on my Facebook page, and then a fuller review that was soon published. In the published review, I expressed my disappointment over the book’s thematic and linguistic texture. True, Welcome to Lagos had some relatively impressive moments, some bouts of respite in the otherwise dreary reading time I faced when studying it. It tackled real issues in African and Nigerian politics. It showcased Nigerian politics for the thievery it specialised in, and its politicians, for the thieves and occasional “Robin Hoods” they are. The work also showed much of Lagos, and anyone who has lived long enough in the city would have come to terms with the stories she weaved: the touts under the bridge, especially. Welcome to Lagos also showed how the ghost of the Nigerian government hovered around the activities of the media houses, dished out democratised, violent fatwas, and censored journalists to the point of threats and assassination. However, themes are usually not enough to hold a book close to a critic’s heart. In any case, Welcome to Lagos, while it made a generous, although largely forced and stifled effort, to impress, was generally a bad book. But then, I should not have been too quick to judge.

Chibundu Onuzo’s The Spider King’s Daughter takes the form of didacticism that midwifed the Onitsha Market Literature in Nigeria. The Onitsha Market Literature was an important feature in pre-independence Nigerian Literature, shovelling the ice in the way for our modern national literature. Onitsha Market Literature also addressed very topical, usually unilateral, issues, at the end proferring lessons or solutions. In Charles Larson’s 1978 revised version of The Emergence of African Fiction, Larson notes on Onitsha Market Literature that, “These books are significant both as literary efforts and in their revelation of the popular attitudes to socio-cultural phenomenon. We have a new life and a new language. In the unassuming simplicity and directness of Onitsha Market Literature, we find authentic evidence of what these new elements mean to the common man and what his reactions to them.”

The form of style in OML is like the form of the Romance before the rise of the Novel with Daniel Defoe’s 1722 book, Moll Flanders. Before then, fictional characters were static, and they only bore good or bad traits. Their behavioural capacities were absolute, and so we were pulled rudely from the grace of seeing them as anything more or expecting something different from what the writer showed us. The pitfall of the Romance was that it did not show the true reality. Humans, as well as art, are more complicated.

And so, in a large sense, if we choose to take away the diachronic nature of art and its ability to morph in all its facets and adopt itself to the times, we can say that The Spider King’s Daughter told a good story. The extent to which this story was told, as well as how it was told is what leaves ample space for controversy.

The Spider King’s Daughter takes readers through the lives of Runner G (also known as ‘hawker’) as well as Abike Johnson, two teenagers who fall in love with each other. Abike is the wealthy daughter of Olumide Johnson, and Runner G is a hawker whose life would have taken a fortunate turn had his well-to-do lawyer father not died in a car accident. Runner G takes to hawking ice cream on the streets of Lagos where he meets Abike who takes a liking to him and begins to invite him to her home. Runner G, in a plot twist, learns that Olumide Johnson orchestrated his father’s murder in the car accident. Runner G then fights, alongside two other people whom Olumide is discovered to have hurt in the past, to exact vengeance on Olumide.

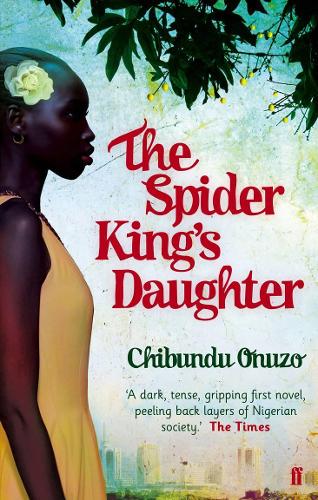

The plot of The Spider King’s Daughter is similar to that of her second novel, Welcome to Lagos, where a runaway army officer teams up with a group of people as they go to find a better life in Lagos. Both novels involve groups of people on a mission to propel a change. Credit should be given to Onuzo for her tackling societal issues and portraying everyday societal nuances. In The Spider King’s Daughter, which she published in 2012 when she was 21 through UK’s Faber and Faber, Onuzo enters the camp of hawkers and trains her camera on them all for us to see. We experience a sliver of the city of Lagos that is usually not underlined in modern literature. In the novel, we see the sufferings faced by the have-nots.

However, the book falls short in many regards. For one, the plot of the work is too slim. The board of a novel gives the writer ample chance to perambulate and saunter into subplots, as many as they can conceive. That’s the rare beauty of the novel, as opposed to the short story with its signature plot singularity and brevity. The Spider King’s Daughter had only a single plot, and so the perceptive reader becomes bored early from the writer’s back and forth style between two characters in a single story. There is no complexity in plot or events. The book is run on funny coincidences and contrived, too-real-to-be-true events. The writer does not use the novel board as effectively as one is expected to, and so we run around a predictable circle, till the end of the novel.

It is appalling to say the least that the author would have the character, Runner G, addressed as “hawker” and other nomenclatic derivatives from the start of the book to the end. I expected the writer to break us from that bubble, and tell us the real name of Runner G, as she did for his sister, Joke, and every other character in the book. A protagonist of that repute deserved a real name, not a pseudonym. But to make matters worse, we read, and we get to understand that Abike never truly gets to know even the name “her hawker” bears. It is amazing that she addresses Runner G as “hawker” from the start of the book till the end.

Proper pre-publication editing should have handled many of the work’s laughable hamartias. The dialogues were completely messy, and it was difficult, if only almost impossible, to know who was speaking at each point in the conversation. Effective use of dialogue tags was summarily dismissed. This raised eyebrows.

Going by the poverty of the plot’s content, admittedly, the book hovered around Abike Johnson and Runner G. The writer probably panted furiously before she eventually found succour in the use of the famous individual narrative approach. I encountered this approach first when I read Isidore Okpewho’s masterly 1976 war novel, The Last Duty. In Okpewho’s novel, each chapter was dedicated to characters in the book, and we experienced their unique, personal versions of the entire story. It is an interesting and complex psycho-narratological technique that has been used in other novels, too, in both African and Western novel theatres. Chibundu Onuzo’s use of this technique calls for serious questioning. Asides from using two distinct voices within same chapters, I was rather confused — initially, I must confess — as to why the author separated the voices with italics for Abike, and normal text for Runner G when she could have made it easier to use simple labelling, or at least parse through separate chapters. But that would have been a much bearable error had the characters not simply have been seeing almost very similar things. Their perspectives were almost same, just with different eyes. Except for a few instances where their vision differs, we only see a strange and absurd repetition of the same event in different eyes and voice, a technique that equals to a waste of book space and time. In a point in the book when Abike tells us that she gives the mechanic 500 naira to repair her car, Runner G brings his perspective to say that it was 1,500 naira. This grave error could have been sorted out away from our eyes before publication, but we encounter the shame of it. Can we also blame perspectives for the instance when Abike closes her car window but still could hear quite clearly Runner G asking her what her name was?

A good critic is a slave to great language. The how of a story is stylistically preferable for many to the what of it. The beauty of a work is in the complexity of its language, and how readers can subject the writer’s words to a second or third consideration. For many critics who have studied time and time over Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, they still return each time to it, and then they gain a different meaning from those same words. The same goes with holy books such as the Bible or Qur’an. A great work is a great ball of language that makes readers think deeply on the apparent, or not, multiplicity of its meanings. Onuzo’s language in The Spider King’s Daughter could have been better tightened and less plain. But that is a different problem, one that cannot be put up to any merit-worthy criticism. Questions of linguistic style should naturally bloom only within the subjective mental boxes of critics, however it goes to give the work meaning regardless. The lack of a beautiful writing style is not exactly wrong if a good message supports it.

There is something about polar opposites. They usually create the same effect on you. It goes for a great book as well as a terrible book. They both leave you stunned. There is a lot to say — maybe too much — but then you cannot exactly express your feelings with words for a moment.

Chibundu Onuzo’s The Spider King’s Daughter had little linguistic nor literary merit to be deserving of a Faber & Faber imprint, to be deserving of any imprint at all. For an elite publishing house that has published works from Kazuo Ishiguro, Paul Muldoon, Philip Larkin, Samuel Beckett, Seamus Heaney, Ted Hughes, and countless other reputable names, I expected better. The work should have been better edited and revised before going into print. The book attempts to toe the line between children’s literature and bad Nollywood drama from the 90s. It fails on both counts.

With unbelievably unnecessary, cheeky and predictable dialogues, to characters that are only as bland as water, to a plot too lean and contrived to be real, to language and creative complexity that can pass for a toddler’s, Chibundu Onuzo fails as a literary writer. The novel was expertly acupunctured with obvious mistakes that could have been sorted out pre-publication. The Spider King’s Daughter is a largely unimpressive novel, undeserving to be in the space on the shelf of any self-respecting, mature reader.

Chibundu Onuzo has finally made me believe — and I believe I speak for many others like me — that thunder can strike twice in one place. I am learning to avoid this troubled spot.

Nzube Nlebedim is a Nigerian writer, poet, journalist, critic, essayist and editor. He holds a BA in English Literature from the University of Lagos, and has radio journalism training from the Nigerian Broadcast Academy. He served as Nigeria field editor for Energy Capital and Power, Mauritius. His works have been widely published and anthologised in Nigeria and Ecuador. He is the founding editor of The Shallow Tales Review. Tweet at him @Nzube Nlebedim.

You mirrored my thoughts.