The consequence of this hostile environment for critics is that criticism as an art form is in decline. The number of critics in the scene reduces by the day…

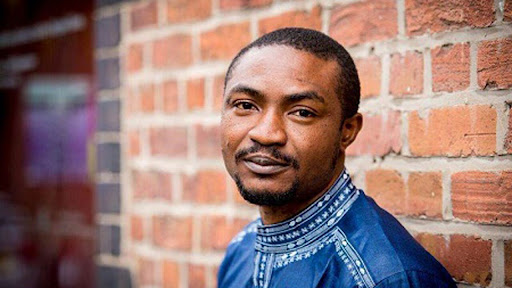

By Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera

On Saturday, August 28, 2021, Nigerian essayist and critic Paul Liam took to Facebook to narrate his displeasure at being publicly berated by the novelist and short story writer, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, during a reading of the latter’s recently published short story collection, Dreams And Assorted Nightmares, at the Spine Label Bookshop in Abuja. According to Liam, Ibrahim had embarrassed him in public as some sort of payback for Liam’s scathing criticism of Ibrahim’s work in a column published in 2016.

In the same Facebook post, Liam went on to narrate how, during the book reading in question, Ibrahim had accused him of “ganging up with his clique” to rubbish him and his art. Paul’s criticism of Ibrahim had come as a rejoinder to a blog post, where the latter had argued that Achebe’s Things Fall Apart would not have achieved its iconic status had it been written in the present day. Ibrahim’s blog post had stirred a minor outrage in Nigerian literary circles at the time, and Paul Liam was one of the writers who disagreed with Ibrahim. Liam would go on to write a not-so-complimentary review of Ibrahim’s NLNG prize-winning novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms. From all indications, there has been no love lost between the two writers.

Ibrahim’s treatment of Paul Liam is typical of the disrespectful attitude with which critics are treated in the Nigerian creative spaces, but in various (and often more gruesome) guises. With respect to literature, some critics have been blacklisted from literary gatherings and festivals, their only crime being that they dared to objectively engage certain works of art. One of the biggest upheavals in the Nigerian literary scene in the middle of 2020 arose when Nigerian editor Otosirieze Obi-Young lost his job at Brittle Paper because of his stand concerning the removal of a post that berated the wife of a governor for refusing to chide her son after the latter threatened to rape the mother of a man with whom he had an argument on Twitter. In 2019, acclaimed music and film critic Oris Aigbokhaevbolo wrote an essay (published in Brittle Paper) where he recounted how he received overwhelming backlash from young writers when he pointed out the wave of “trauma porn.” There are even more gruesome instances in the political scene, where people have disappeared for criticising the government: Nigerian journalist Steve Kefason was detained for over six months, just because he made a Facebook post calling out the Kaduna State government.

The consequence of this hostile environment for critics is that criticism as an art form is in decline. The number of critics in the scene reduces by the day, and there were fewer in-depth discussions about the current direction of art. Every society is a function of the quality of art that exists therein, and more importantly, the level of freedom with which artists express themselves. When it comes to Nigeria, one can infer that the creative scene has grown more authoritative than egalitarian, and consequently, the art in these climes is experiencing a growth spurt. Artists are becoming “tyrannical”.

Critics are often hated because they seem to wait around at every corner, waiting to pounce on the mistake of the creative and remind him of his imperfection. But a healthy society is one that acknowledges the role of a critic and recognizes the fact that a critic lets the society know where it is headed by virtue of its choices. The dearth of criticism in any given society hints at tyranny. Such a society commits artistic suicide because critical art is substituted for propaganda, and true self-reflection is jettisoned in favour of image laundering. The more a society embraces art criticism, the closer it gets to becoming truly democratic.

The tenets that uphold tyrannical dictatorships are so ugly that they involve the use of violence in blocking everything that attempts to provide a window into the truth. It is for this reason that in Stalin’s Russia, art was all but proscribed, and in Hitler’s Germany truth was sacrificed on the altar of propaganda. In many African countries, literature is suffering. Nigeria in particular has despotic governors courting writers to launder their image, and no efforts are being made to revive the ailing publishing industries which bore the brunt of the oppressive military regimes of the 80s and 90s.

In the past six and half years, Nigeria has slid into a cruel dictatorship under the current administration. This is the time when people ought to turn to the arts for rescue, when criticism should become popular, and to borrow from Toni Morrison, when artists ought to go to work. But a curious thing is happening: as political despots rear their tyrannical heads, the artists themselves are becoming tyrants too. A situation where creatives now await the perfect opportunity to berate their critics, or where critics are blackballed for asking writers questions about their choices and how it affects society, calls for worry. There is no existent structure in the mainstream literary scene that encourages the growth of contrarian writing or independent thought.

In Nigeria, the critic is accused of “holding too tightly to nostalgia”, policing other writers to fit into his idea of a writer, and even telling others what to write. A good case can be made for the validity of these (non-peculiar) claims that some critics are in fact guilty of these charges, but that is only part of the story. In today’s art scene, it could be argued that many contemporary Nigerian poets write pieces that all look the same, and that the desire to be published by American and foreign journals has influenced their art to assume homogenous shape; ten years from now, many of these poets will look at their current work with disgust. But critics have gotten stick for even daring to point this out. Oris Aigbokhaevbolo was harangued and pilloried for pointing out the wave of “trauma writing” as reflected in the tone of essays published by Catapult a few years ago. The writers whose submissions were being accepted by Catapult at the time perceived his statement as an attack on their craft.

Art is affected by the psychology of societal conditioning which it is ideally supposed to break away from, and in such cases, it is the duty of the artist to point it out. To do this, he must first assume the mindset of a critic. It is important to see art created in isolation, and ultimately, to examine the bigger picture that each piece of art represents. Aigbokhaevbolo’s only sin was to point out how a number of Nigerians were being published on an international platform in large numbers, and finding an uncanny resemblance between each essay. It’s not out of place to express skepticism that writers from a hugely populated country like Nigeria, rich in all kinds of stories, are only writing about trauma.

Many young writers today are indeed ready to go to war in order to defend their unhealthy self-absorption. Over the years, many writers have bought into the idea that the writer had no responsibility to society. There was a little paradigm shift after Otosirieze was forced to leave Brittle Paper and a large community of young writers stood with him, and then the #EndSARS protests sprung up not too long after. This change did not necessarily spring forth a generation of critics, but it left the younger generation more aware of the futility of its aloofness.

More creatives should learn to examine the arts through critical lenses, but more importantly, accept criticism of their work. It is shameful to see Nollywood filmmakers baying for blood when they stumble on bad reviews of their movies. It is the critic who teaches us that a good piece of art is more intelligent than its creator, and is capable of saying more than the artist knows. Criticism is not a perfect art form, and by no means should perfection be expected of the critic, but their existence should be seen as a necessary arbiter of growth, as well as society’s continual efforts to improve itself.

Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera is a writer and freelance journalist. Follow him on Twitter @ChukwuderaEdozi or reach him at chukwuderamichael@gmail.com

Aaah.

This was a rich banquet. Well cooked, well edited, well served, and certainly well enjoyed. I can hardly find anything to argue with in this essay.

The role of the artist is more than chronicler of the times, the artist must also call out evil, even when the evil is in the artistic community. That is honest work.

Well done, Chiedoziem. Super proud, as always.

A. O. Scott: Art gives us freedom. It is the duty of criticism to determine what to do with that freedom.

Criticism is itself a art form, and as art form it should be constructive and creative .