In the summer of 2019, as what later became Caleb Nelson’s Open Water was produced, he might never have known the influence Cole would have on this novel of his…

By Nzube Nlebedim

Has linguistics been able to accommodate the language of photography and music? Has melding music and pictures into fiction been any possible, any successful? How effective has this been in literature? Caleb Azumah Nelson experiments with it.

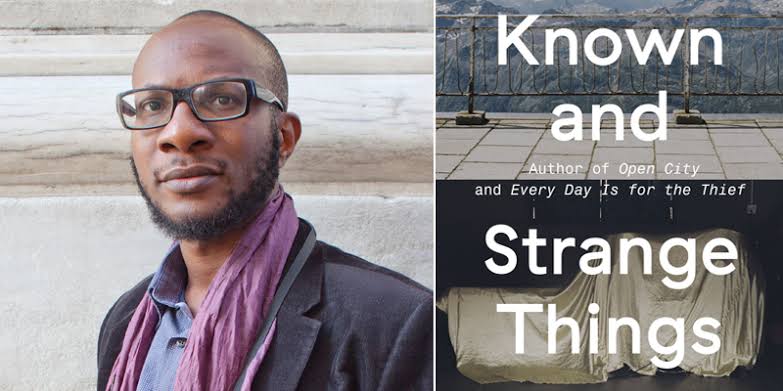

In August 2016, the same year Teju Cole published his Known and Strange Things, a New York Times article carried the headline, “Teju Cole’s Essays Build Connections Between African and Western Art.” That article noted that the book “…journeys through all the landscapes he has access to: international, personal, cultural, technological and emotional.” Teju Cole’s essays are naturally and deliberately unhomed, somewhat ostracised, and this makes his works beautiful: their ability to cut through cultures, time, and place.

In the summer of 2019, as Nelson produced what would become Open Water, he might never have known the influence Cole would have on this novel of his. It is a very likely premise that Cole’s KAST laid the foundation for the fiber of Nelson’s Open Water. The two writers work from the same wavelength, weaving paralinguistic cues and making beauty from them. The intertextuality is golden, the messages raw and searing.

Open Water is instructive. Told in second person, the unnamed protagonist tries to find his feet, absorbing and surviving the harsh and stark racial realities in London. He’s part Ghanaian, part British, and ultimately a black man. He works as a photographer. The writer paints him as introspective and sensitive. He is careful, as water.

He is unable to get over the death of David, a fellow young black man whose death he witnessed, and he loses his relationship with his friend and lover, an unnamed black dancer who is seen to usually move between London and Dublin. Although he manages to hold a photography job, he finds it difficult to blend into the racist London system splattered with police violence and brutality against black Londoners.

In an interview with Mary Wang, published on Guernica in April 2021, Nelson says that “I’m always collating and collaging, trying to see how images work off one another. I discovered that if I referenced images or films in Open Water, it would take the narrative into another dimension.” And this is what he does with the book. Really, it is the effect it leaves on the more perceptive reader. Nelson takes the readers to another plane, different from what is obtainable in regular prose readings. He writes music and photography at the same time, in the same space.

The protagonist of Open Water asks at the tail end of the novel: “How do you say the things for which there is no language?” Nelson chooses pictures.

Photography found voice and language in Caleb Nelson’s Open Water. Nelson, like Cole, shows how photography and music play vital roles in the life of the Black African away from home, in strange and unknown places. This is a technique and style that isn’t replete in Diasporic African literature. Diasporic African literature, itself, is only emerging with writers such as Taiye Selasie (Ghana Must Go), Teju Cole (Open City), Yaa Gyasi (Homegoing), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Americanah), NoViolet Bulawayo (We Need New Names), Chika Unigwe (On Black Sisters’ Street), and others considered to be leaders in this new genre.

“While these Africans have not established significant political relevance in London, they have contributed to the society as a whole,” Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo says in his Quartz Africa, May 2020 article.

Much credence is being given Diasporic African literature today, and this was crowned with Abdulrazak Gurnah’s clinching of the 2021 Nobel Prize For Literature, for his work in illuminating colonialism. Gurnah reiterates the situation of Africans away from home when he notes in a BBC interview shortly after this victory, that Africans in the Diaspora are not simply there to take; many of them are there to improve, and have significantly made better, the economies and culture of the host countries.

Nelson’s language and pacing is slow, patient, measured, and determined. The words, characters and events seem to move about in loops, on the boundaries of concentric circles, but, eventually, they move away from their hold. The story moves like still water, slowly, calmly, silently, but assuredly.

Nelson’s language is dense, photographic, musical, alluring. We can feel the monochrome, the vintage silence of the characters and events. This monochromatic rendering is symbolic. There is a gloom it gives to the story, this blackness. This cinematic technique is used in films such as Rebecca Hall’s Passing (2021) as well as Sam Levinson’s Malcolm and Marie (2021). In Open Water, the seeming kinesthetic uncertainty of the plot gives the work depth.

And do we not perceive, in the work, vinyl music playing in loops and refrains? The words of the author repeat again and again across the story. They are repetitive and poignant. We are immersed in this body of epic poetry, only that it is prose. In the interview with Wang, on rhythm, Nelson notes that, “I used loops and refrains throughout the text. I was interested in what emerges when you revisit a line or phrase, and you’re seeing the same thing, except the narrative has moved on, has changed, and so have you as a reader.” The characters and plot fight to find their way through the denseness of the writer’s narration, as much as they fight to survive London.

You prod the pain in your left side and want to be made light. You pray with every action this will not be the day. Every day is the day, but you pray this day is not the day. Your mother prays every day that this will not be the day. You hear her through the bathroom door, praying for her sons, even as you play rapper while you swim in shallow water.

Open Water details love, the intricacies of being unhomed and othered. Racial reality is a body of water that drowns quickly, unexpectedly. There is vibrant fear in the air for those lucky to survive the drowning. Leon the barber is one of them. An old man from Ghana, like the narrator, Leon has become inured in the ways of England, but still doesn’t consider it home.

In a conversation between the narrator and Leon about Ghana, Leon tells the other man that, “my body is back but my mind is still there.” It is a statement charged with unsaid words. It is then instructive when he gives the narrator The Destruction of Black Civilization by Chancellor Williams. It is also ironical that soon after they experience another case of racial violence.

Nelson is toeing a fresh line in modern diasporic fiction. He’s doing it differently, with flair, not regarding how others before him have done it. And it works for him. Nelson has created in this debut a brilliant work of monochromatic art.

Nzube Nlebedim is a Nigerian creative, critic, and editor. He is the founding editor of The Shallow Tales Review, an electronic literary magazine curating African literature and Black writing.