Women use themselves as rods of chastisement on their fellow women, and this becomes a ready tool for the enforcement of patriarchy in igbo society…

By Joshua Omenga

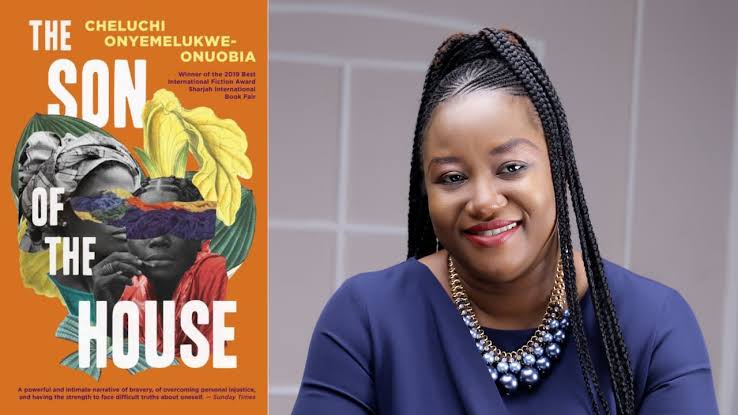

“The Son of the House” proved a ‘classic’ read for me despite my initial scepticism when I encountered its narrative voice, for I have a negative bias for stories written in the first person. Past the prologue, however, I ceased to notice the narrative voice as the story takes over. The transitions from the past to the present are seamless. And while the ending of the story is quite predictable for the reader (who has facts unavailable to the characters themselves), it is almost like an abrupt cessation of pleasure at its peak. A part of me wants more; another part of me prefers the mystery of its unresolved ending.

“The Son of the House” is an ironical title, for it suggests a story with male protagonists. But perhaps the title is significant for that reason: “The Son of the House” portrays the role of women through contrast with the role of men in the Igbo society it is set. Although the story centres on women, women are portrayed as insignificant without men—either as husbands or as sons. The lives of the female characters revolve around their male counterparts, more consciously than unconsciously. The males are viewed as foundations of the family and society, and a family without a male child is to all intents and purposes incomplete, irrespective of how many female children it may have.

Thus, the prime protagonist, Nwabulu, an only (female) child of her mother, is tolerated only because a female child is better than no child at all, something to hold on to until the arrival of a male child. For Julie, her drunkard brother is more precious to the family than her, and her success is viewed as a curse rather than a blessing, something which her family believes should have been bestowed on her brother than on her. Her father wishes she were a son rather than a daughter, much as Okonkwo in Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart” wishes Ezinne were his son rather than simply his daughter.

The place of wives in their husbands’ houses, as a rule, is uncertain until they have given birth to a son or sons. Mama Nkemdilim, despite having many female children, only feels assured when she gives birth to a male child. Urenna, Nwabulu’s estranged lover who abandons her after impregnating her, is the only child of his mother mentioned by name and crowned as “the son of the house”; his sisters are simply noted as side characters who are insignificant to both the family and the story.

Nwabulu is employed as a maid in “Mummy’s” house to take special care of Ikenna as “the son of the house.” Mama Nathan is assured of her son’s lineage only after Nwabulu gives birth to a son, Ezinwa, for the deceased Nathan; and taking the child, she has no further need of its mother. Despite giving birth to three female children, Eugene’s first wife is easily displaced by Julie who pretends to be pregnant for a “son”—something which the first wife has failed to achieve.

Julie’s own desperation for a son to maintain her place in her husband’s house leads her into stealing a male child (Ezinwa, whom she called Afam), after which no one questions her place in Eugene’s home any longer. No occasion is lost to emphasise the prime place of male children in the family, and the reciprocal insignificance of female children. Indeed, one of the new and condemnable trends in the emerging generation is men’s acceptance and contentment with only female children, like Julie’s “son” Afam.

The tone of “The Son of the House” portrays it as a feminist narrative which attempts to assert the place of women in a patriarchal society. But if the writer has set out to achieve this, the result is manifestly a negative success—unless the writer intends the deliberate irony in her female characters’ lives or to simply portray the inescapable reality of the Igbo society of which she writes. Women use themselves as rods of chastisement on their fellow women, and this becomes a ready tool for the enforcement of patriarchy.

The female characters in the story direct their powers not against their male persecutors but to the persecution of their fellow women. Mama Nkemdilim commences the trend with her treatment of Nwabulu. When Papa Emma defiles Nwabulu when she was 12, Mama Emma attacks Nwabulu rather than her paedophilic husband. Mama Nathan, to keep her deceased son’s lineage, plots to marry Nwabulu for Nathan, a deceased man. Against even the pleas of men, Mama Nathan separates and prevents Nwabulu from seeing her own son at a very tender age. Perhaps the most telling of these persecutions of fellow women is Julie’s.

Julie tactfully implants herself into the house of Eugene, a married man, tricks him into marrying her and persuades him to abandon his first wife. Julie justifies her action, as does Julie’s mother, by claiming that no one expects a man without a son to not marry another woman who can give him one. Still, Julie is wise in her own affairs, for, when presented the same cup she fed others—when Eugene impregnates another girl and wishes to marry her as he had married Julie—Julie devises a means to get rid of the young girl, with a promise to take care of the girl’s baby if it turns out to be a male.

When Julie herself delays in bringing the promised son into Eugene’s family, Eugene’s sisters visit her with their wrath, determined to kick her out of her husband’s house.

Patriarchy is a recurrent theme in literary works set in Igbo society. Older novels like “Things Fall Apart,” “The Joys of Motherhood” by Buchi Emecheta, and “Efuru” by Flora Nwapa do not attempt to veil male dominance in Igbo society, thus making patriarchy easier to identify and criticise. However, contemporary novels, in their attempts to excoriate patriarchy in Igbo society, often end up indicting women for their roles in promoting patriarchy. They portray women who consistently refuse to admit, much less question, their own, perhaps inadvertent roles, in promoting patriarchy.

Most Igbo cultural institutions which persecute women are administered by women, and naturally die away if undermined by them. There is self destruct. For example, in Akachi Adimora Ezeigbo’s “The Last of the Strong Ones,” the women break the bonds of their society and liberate themselves from the restrictions that keep them docile. The result: the women almost succeeded in uprooting colonialism where the men had been powerless, showing in fact that women can and often prove stronger than men when they are determined on a course of action.

Even in “Things Fall Apart,” in the patriarchal society of Umuofia, men do not generally suppress women in areas where women manifest their power; in fact, the society recognises the prime role of women in every man’s life (demonstrated in Okonkwo’s refuge in his mother’s village during his exile for manslaughter, and in his claim that nneka, or mother is supreme).

Indeed, patriarchy represses women only insofar as they do not express their latent power. It seems, therefore, that female subjugation in Igbo patriarchal societies is more a product of women’s refusal to exercise their latent power for their own liberation than men’s conscious repression of women.

In “The Son of the House,” Nwabulu remains miserable only for as long as she accepts the societal depiction of women as subservient to men, but the moment she takes charge of her life, she acquires a personality independent of men, and is respected as such.

Julie remains fearful and unsure of her life’s trajectory despite her early financial success until she takes charge of her life and finds out that men are pliable, after all. In almost all instances in these patriarchal stories, men’s show of force often surrenders to women’s retaliation or manipulation. But women do not exploit their powers in their own general (as opposed to mere individual) interests. This is one of the reasons for the persistence of patriarchy in the Igbo society of which “The Son of the House” is set.

But perhaps for all that, “The Son of the House” is a story of redemption, not of the society, but of the characters. Seen in that light, the feminist mission of the writer (if she has any such mission) is a success. The final part of the story brings together the two protagonists, Nwabulu and Julie, in an unusual collision.

Just when their friendship is established, they are put in the awkward position of recognising in each other a conflict of interest. Nwabulu learns that her long-lost son is in fact alive—stolen by Julie herself! And Julie realises that the crime she wishes to hide for life can no longer be concealed. Nwabulu is understandably furious, but Julie’s wise admittance of her wrong calms her down, and in the final moment, Nwabulu lets go of her anger (even when unable to forgive the wrong) and their friendship becomes one of understanding.

To spare the characters (or perhaps the reader) awkward moments, the writer ends the story without furthering it to the encounter of Afam (or Ezinwa) with his two “mothers” (Nwabulu and Julie). The unresolved ending of the story allows the reader to choose either a happy or tragic ending. I for one chose to go no farther than the writer.

Joshua Omenga is a legal practitioner and writer of African speculative and literary fiction.

This is fantastic.

This piece has done justice to the dilemma in which women face in the society, not even when the clamour for equality is at its be peak in our current society against the alledged importance of a male child in the house.

Contrary to what was portrayed in the Novel, Could the concept of patriarchy be corrected in homes or Lineages.