Today, a little over 25 years after his death, Nnamdi Azikiwe’s legacy is almost relegated especially in the southeast where he came from; his place in history, when talked about, is rigorously questioned by his own people, many of who blatantly write him off….

Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera

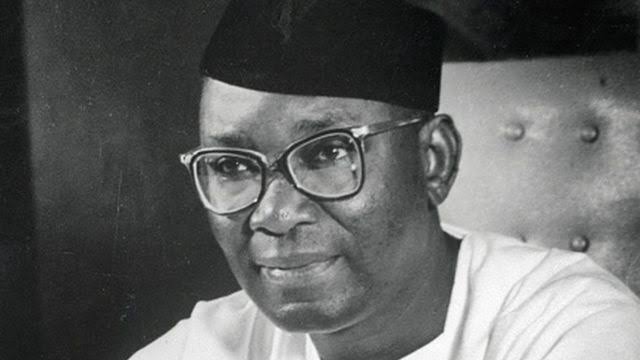

Today, November 16th, 2021, marks the 117th birthday of Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe. Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera pens down an opinion on the great Nigerian leader, and why it seems his legacy is rubbing off.

Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe is perhaps the only one among the Pan-African leaders and soldiers of African Independence who did not, in totality, rule the country whose independence they fought for. Yet, Zik as he was fondly called, was the father of African nationalism, and he inspired other leaders like Kwame Nkruma of Ghana, Homphouet Boigny of Cote D’Ivoire, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, and many more across Africa. However, 25 years after his death, Nnamdi Azikiwe’s legacies are very light on the memory; his role in history is becoming increasingly less important to his people, as the country he fought for continuously retrogresses.

Azikiwe had returned from America in 1934 after an excellent education, where he studied at Storer College, Howard University, University of Pennsylvania, and taught political science at Lincoln University where he developed a flair for questioning colonial rhetoric. In Ghana, he took up a job as an editor of the African Morning Post. Through sheer brilliance, he turned the paper into an effective tool for exposing colonialist propaganda and enlightening fellow Africans.

In 1937, he returned to Nigeria, and having gained more experienced, found four different newspapers which he strategically positioned in Lagos, Kano, Port Harcourt and Ibadan. With Herbert Macaulay, he founded the National Congress for Nigeria and the Cameroon (NCNC) which was the first Nigerian political party, aimed at building the ideological framework of Nigerians, and to wage political war against the colonialists.

From the mid 1940s after Herbert Macaulay’s death until Nigeria got independence in 1960, Nnamdi Azikiwe was the most influential Nigerian with loyalists from every part of the country, mainly because he espoused a brand of politics that superseded ethnic sentiments. So influential was Zik that in the 1940s, some young Nigerian men at the time including Kolawole Balogun, M.C.K Ajuluchukwu, Abiodun Aloba, Nduka Eze, G. Onyeagbula, M. Aina, G. Ebo, and many others came together and formed a political movement which Dr. Nwafor Orizu in his 1954 book called Zikism, with Balogun as its first president and Ajuluchukwu as first Secretary-General.

The movement espoused ideals such as spiritual balance, social regeneration, economic determinism, mental emancipation, and political resurgence.

The group was described by Stephen Kola Balogun, son of its first president, as “the most influential youth movement in the history of Nigeria” in an article in the Guardian Nigeria. However, Nnamdi Azikiwe did not lend so much support to the group, and soon left that brand of nationalism to espouse other ideas like free trade, self-reliance, constitutionalism and moral rearmament. He even criticised the movement for its radicalism.

Azikiwe’s new found averseness to radicalism would eventually result in him being sidestepped by young army officers in the 1966 coup. Akintunde Agunbiade attributed Zik’s abandonment of Zikism to the fact that he, “…might have realized that it would be better to agitate for freedom within the framework of the colonial system, rather than advocate for its tearing down.“

Azikiwe remained largely influential throughout the 1950s, and after Nigeria’s independence, Nnamdi Azikiwe instantly became a national hero, his legacy set on a path to immortality. But the country he fought for was soon overridden by corruption, and ethnic jingoism. Before the first six years of the country’s existence, some overzealous young soldiers staged a coup to overthrow the present government where all the premiers and traditional rulers of various ethnicities were killed, except for Nnamdi Azikiwe who was out of the country at the time, and Michael Okpara who was with the Ethiopian Monarch at the time of the attack.

This led to a predominant sentiment among the army officers of other ethnicities, mostly Northerners, that the coup had been an Igbo one. And so Igbo people were massacred all over the north and many other parts of Nigeria. Nnamdi Azikiwe’s political image might have suffered a fatal blow after the coup carried out by young officers who were in part disappointed with how he had grown to put up with the corrupt system.

Emefiena Ezeani in his book, “In Biafra, Africa died,” recounted the comments made by one of the leaders of the coups, Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna, about Zik, when Ifeajuna complained of Zik’s unwillingness to put his people first before himself, and how his compromise was allowing for the growth of ethnic bigotry than receding it. Zik, by then, in his 60s, had grown more introspective, and he seemed to be overridden by the fresh wave of radicalism of the younger generation, most of whom were in their early 30s by the time.

When the counter coup came, and later the Aburi accord was not honoured by the Nigerian government, Biafra seceded, and the civil war began. Nnamdi Azikiwe found himself in a battle he did not choose, and a fate whose engineering he was not part of, and would have given everything to quash it. It is not out of place to suppose that perhaps, he carried out diplomatic duties for Biafra with fear, uncertainty, and gnashing teeth.

But then, his influence was enough to help secure the support of some African countries including Cote D’Ivoire, Gabon, Tanzania and Zambia. And so when it seemed that the war was going to ultimately favour the Nigerian side, he crossed over, and in a speech, referred to Biafrans as rebels.

In the Nigerian state which had gained from the war, Nnamdi Azikiwe never again rose to his enviable prominence. A new dispensation arose which gave rise to politicians with support base to rival his own, and there were the ethnic politics which became more pronounced and has since been a gulf to Igbo people at the federal level.

On return to civilian government, alongside Alhaji Shehu Shagari and Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Zik contested for presidency in 1979, but lost to Awolowo. Civilian rule was abruptly interrupted after just four years in 1983 by the Buhari/Idiagbon pair, and before Nigeria returned again to civilian rule in 1999, Nnamdi Azikiwe was three years gone.

Today, a little over 25 years after his death, Azikiwe’s legacy is almost relegated especially in the southeast where he came from; his place in history, when talked about, is rigorously questioned by his own people, many of who blatantly write him off.

On the national scene, History being banned from schools worsened the matter. And although his name adorns the second most valuable denomination of the Nigerian currency, the second biggest university in the southeast is named after him and one of the biggest Nigerian airport is named after him, and the national honours given to him surpass that of every Nigerian in history, the knowledge of the younger generation of him is marginal, and his legacy has grown largely unimportant.

A politician of Nnamdi Azikiwe’s caliber in 2021 Nigeria would be a golden dream. A pioneer on many levels, he excelled both in the academic, business, political worlds, and was a fine writer and thinker. Not only were his political strides great and widespread all over Africa, he, alongside Kwame Nkrumah were leaders of the Pan-Africanist movement.

He inspired many African leaders who were and became heads-of-state in their countries during the Biafran war, and recognised the self-determination of Biafra as a right path to the Pan-Africanist struggle. Back in Nigeria, he inspired much more, including Michael Okpara and S.L. Akintola, both premiers of the Eastern and Western regions respectively who laid the blueprints for the development of their regions, which largely depended on industrial and agricultural reforms.

Not only did Azikiwe inspire politicians, he was a pioneer of a system which brought about many of the leading African economists, physicians, poets, engineers, etc., of his time. He founded the University of Nigeria, Nsukka to promote tertiary education in the southeast. Indeed, one cannot, on honest introspection, not see the strides achieved by the genius that was Azikiwe.

It is challenging to put fingers to the many factors that have stood against Azikiwe’s name in history, but the most glaring is that the brand of nationalism which he preached has not stood the test of time. Nigeria as a country in 2021 is more disunited than it has been since 1970 when the war supposedly ended.

The Igbo people are once again consumed in the struggle for self-determination after continual marginalisation and the absence of national growth over fifty years after the war. Azikiwe’s vibrant politics is in sharp contrast from his place in history; the country he fought for is at loggerheads with history. Most of Azikiwe’s legacies lie almost forgotten.

There is a lot of inspiration to be culled from the Nnamdi Azikiwe story. I remember having goosebumps seeing a short documentary fifteen years ago about Azikiwe on Silverbird TV. His litany of achievements are almost endless. But the greater lesson, I think, is in the fact that, despite his glories, his place in history is not especially a fond one. One of the biggest ironies in the story is how Azikiwe’s people have been haunted the most by the Nigeria he fought for. In hindsight now, it appears that even Africa was not ripe for the kind of nationalism he espoused.

Cooperation between various ethnicities are not built on optimism and the poetry of brotherhood; if it must succeed, there must be a strong socioeconomic backbone for it. That backbone was not built during the Independent struggle. There was no proper ideology tying the three major ethnic groups in Nigeria together. Obafemi Awolowo said this very clearly in 1948 when he voiced out his pessimism for the creation of a united Nigeria. Awolowo, though not as grand as Azikiwe, and despite his role in the genocide on Biafra, appears to have a fonder spot in the heart of his people, and by extension has a more profound legacy.

In Nigeria today, people have grown to believe less in the unity of the country and by extension what Azikiwe fought for. And as people become averse to the unity of the country, it becomes more difficult to talk about Azikiwe in glowing terms. Perhaps, the biggest lesson from Azikiwe is that all politics is local, and best played locally before one seeks the collaboration of external groups. Yet, we should study Azikiwe, and talk more about him, at least, to learn from the things he did not get right. Perhaps, in this light, we may come to see the gift of the man in paradox.

Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera is a writer and editor. Reach him at Chukwuderamichael@gmail.com, or Follow him on Twitter @ChukwuderaEdozi.

Very true Micheal,very true. Azikiwe despite his elevated position did not for his people. Since I’ve been reading about Biafra,never have I come across his name. Who will remember? Is it the Yoruba or Hausa? He failed his people and the result is,his legacy will soon be washed away by the tides of time.