These strides are the foundational blocks toward a sturdy industry on its pathway to infiltrating the world with its films and TV shows.

By Seyi Lasisi

From its modest beginnings in the 90s, the neophyte Nigerian film industry has been gradually attracting Nigerian viewership. This burgeoning industry was a collage of distinct filmmakers who were learning to use their filmmaking skills to document variant experiences. Film production took place in various parts of the country, and reflected the social realities of Nigerians. But these creations were notable for their subpar production and technical value – unsatisfactory sound design, cinematography, and editing.

Taking the social realist pathway, the stories were adopted from the streets of Nigeria, while beaming a floodlight on relatable situations woven around the daily realities of the working class and middle class. Films such as Osoufia in London, Diamond Ring, and Koto Aiye – which ranged from comedy to horror – cast the gaze of audiences on Nigerian beliefs, culture, and values. Produced in prolific numbers, these films endeared viewers, and as the blossoming film industry adopted the term “Nollywood”, it kept attracting viewers beyond the shores of Nigeria.

It is 2023 now. The film industry has crept beyond its infantile production and technical value stage. A sense of advancement has engulfed Nigeria’s film production, and film production today, much like the pioneering films of the 90s, still charms viewers. With Nigerian films attracting viewership beyond the shores of Africa, the industry is moving towards maturity. Nollywood is having its moment, similar to the often-reiterated “Afrobeat to the world” movement which is true for the music industry.

The Nigerian film industry has taken a substantial bite on streaming platforms. Nollywood’s most hefty budget production of 2023, The Black Book is memorable for various reasons. The Editi Effiong-directed film has ranked in the Top 10 films in sixty-nine countries on Netflix’s global charts. Similarly, the numbers for the Bunmi Ajakaiye-directed Glamour Girls (2022) are encouraging. The film topped the Netflix Top 10 films in fifty-four countries. These stellar chart-topping metrics boost the morale of both filmmakers and critics and are remarkable prototypes for investors to take risks with the industry. A prolific increase in investment – from venture capitalists and streaming platforms – will result in more training opportunities for filmmakers, and more exposure, where filmmakers can begin to explore the usage of advanced filmmaking equipment. These strides are the foundational blocks toward a sturdy industry on its pathway to infiltrating the world with its films and TV shows.

(Read also: Funding and Collaboration in Nollywood: What Could “The Black Book” Tech Investors Mean for Filmmakers in Nigeria?)

The industry is also slowly moving past its caustic and crude portrayal of women in films as docile and submissive. There is an ascendancy of more nuanced female-focused films in the industry. The Kemi Adetiba-directed King of Boys (2018), Jade Osiberu’s Isoken (2017), and Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart (2018) portray Nigerian women outside of the traditional confines. With lead female characters who are more nuanced and empowered being depicted onscreen, viewers seeking refreshing and more feminist-minded narratives are attractive.

Although crew members – editors, gaffers, and sound recorders, occasionally talk about the unfair treatment they grapple with in the film industry, there’s a sense of growth that has saturated the production of Nollywood films. Picture-wise, Nollywood films and TV shows weren’t so easy on the eyes, and the camera work didn’t always translate into aesthetically appealing visuals. However, cinematographers like Adeoluwa Owu and Barnabas Emordi are slowly building their visual language. Emordi’s black-and-white cinematography beautifully captures the noir landscape of Niyi Akinmolayan’s House of Secrets (2023). Owu’s cinematography skill captures the African traditional landscape in Jagun Jagun (2023) and The Griot (2022).

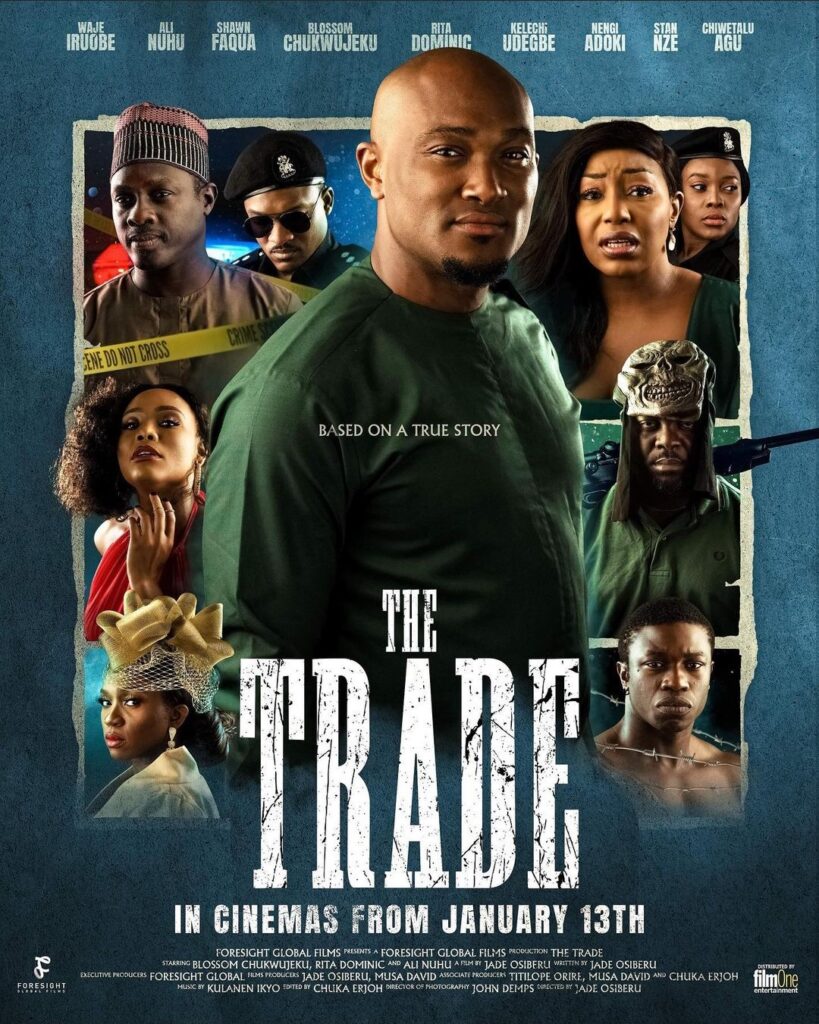

Leading the sonic landscape are Kulanen Ikyo, Tolu Obanro, and Adam Songbird building their portfolio in sound design. Ikyo has worked as a composer in defining Nollywood films and TV shows, to which The Black Book, The Trade, Oloture, Lionheart, and Crime and Justice Lagos are notable mentions in his portfolio. Obanro and Songbird’s collaborative effort in curating the sound for House of Secrets made the cinematic experience remarkable. Martini Akande and Biyi Toluwalase are also holding the fort with editing. Akande’s editing in Gangs of Lagos and that of Toluwalase in Brotherhood matches the fast-paced movement of both films.

Harmonising these distinct filmmaking departments together are directors, of which Akinmolayan, Osiberu, Kayode Kasum, Ebuka Njoku, and Kunle Afolayan are part. Akinmolayan through Anthills Studio keeps delivering experimental films. Osiberu’s not-often-talked-about The Trade is a realistic Nigerian “action” film. Njoku’s debut feature film, Yahoo+ challenges the monolithic perception of the ritual act associated with Yahoo boys. Afolayan keeps upholding the cultural heritage of the Yoruba culture in his films and TV shows. In all, the industry is teeming towards its fertile stage.

(Read also: From Amaka Igwe to Jade Osiberu, Nollywood Female Filmmakers are the New King of Boys)

Independent filmmakers are also creating compelling works outside of the mainstream. The S16 trio: Abba T. Makama, Michael Omonua, and C.J. ”Fiery” Obasi, since their arrival in the film industry, have positioned themselves as “disruptive” filmmakers breaking down the patent-esque identity of Nigerian films. Makama’s The Lost Okoroshi (2019) and Green White Green (2016), Omonua’s short film Rehearsal (2021) which he’s developing into a feature, and Obasi’s O-Town (2015) and Mami Wata (2023) have pushed viewers’ imagination of cinematic possibilities. The experimental and genre-blending tendencies of these films keep courting Nigerian and Western audiences. Chuko and Arie Esiri’s migration-themed Eyimofe, which can be called one of Nollywood’s modern-day classics, won multiple awards at the African Movie Academy Award (AMAA) in 2021. This year, Mami Wata became the debut indigenous Nigerian film to have its world premiere at the Sundance International Film Festival. At its African premiere this year in the Pan-African Film & TV Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO), the folkloric-esque film won the Prix de la Critique Pauline S. Vieyra (African Critics Award) at the Special Awards Gala, among many other awards.

Babatunde Apalowo’s All the Colours of the World are Between Black and White, keeps touring festival circuits. After its world premiere at Berlinale (where it won the Teddy Award for best LGBTQIA+ feature film), it has screened at seventy-eight International film festivals, winning multiple awards: Jury Best Director at Premios Del Jurado and Best Cinematography at Raindance Film Festival 2023 amongst others. Recently, Omonua and Obasi curated and programmed fifteen indie-produced and experimental Nigerian short films, “Nigerian New Wave” at the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur, Switzerland’s major short film festival, attesting to the potential of indie filmmakers in the industry. These films and filmmakers are slowly and painstakingly building an audience for their works, and by extension, for the film industry. In their individual ways, these films sustain Nigerians’ belief that our stories can captivate audiences worldwide.

(Read also: The S16 Collective: Who are These Nigerian Indie Filmmakers)

But even as the film industry gains ascendancy – striking international deals and partnerships and attempting to dominate other film markets outside Africa – the film industry still struggles in its storyline. The storyline and plot development are sometimes headache-inducing and puzzling. In a recent interview with Afrocritik, Kasum acknowledged the spontaneous growth eclipsing the Nigerian film industry, recognising the improved production value of Nollywood’s production. However, the director of Oga Bolaji still wants Nigerian filmmakers to be pedantic in their storytelling. “Our storytelling needs to be improved. And I like the fact that Nollywood filmmakers are looking into that. We are trying to get our stories to the next level. I don’t think it is production value. I say this is because there is more funding coming into the industry now,” Kasum said. Kasum’s words are deeply reflective of the clamour by Nollywood film enthusiasts and critics.

All these said, the film industry is marching towards an admirable future. And as Nigerian award-winning producer of Mami Wata, Oge Obasi said, “Whatever you think is happening, or whatever greatness you think you’re seeing, just know that we’ve barely scratched the surface. As we say in old Nollywood – this is just the beginning.”

Seyi Lasisi is a Nigerian student with an obsessive interest in Nigerian and African films as an art form. His film criticism aspires to engage the subtle and obvious politics, sentiments, and opinions of the filmmaker to see how it aligns with reality. He tweets @SeyiVortex. Email: seyi.lasisi@afrocritik.com.