Although their endeavours are often solitary, encouraged by few friends and minimal funding, these filmmakers and their films are creating a distinct blueprint for ambitious Nigerian filmmakers and Nigerian film culture…

By Seyi Lasisi

Mami Wata, the C.J. ‘Fiery’ Obasi-directed film, had its premiere at the Sundance Festival five days ago. Eyimofe, the immigration-focused film by the Esiri duo of Arie and Chuko Esiri, had its premiere in Berlin in 2020. In the span of three years, these Nigerian filmmakers had created an enviable track record for other ambitious Nigerian filmmakers, and, by extension, made themselves the center of attention in African filmmaking in the international scene. In premiering at these often-ignored film festivals by filmmakers with kinship with Nigeria, Eyimofe answered Wilfred Okichie’s question. No, the Berlinale doesn’t have a Nollywood problem. And Obasi’s presence with the Mami Wata‘s film crew means Nollywood is having its first dance at Sundance.

Mainstream Nollywood filmmakers have hogged for themselves the attention of Nigerian audiences. Though the conversation of creating film content for global audiences, being propelled by streaming platforms, is led by well-known Nollywood filmmakers, it’s the indie filmmakers — obscure names, if you may, that are garnering International acclaim.

The Dogme 95 was created in 1995 by Danish filmmakers, Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, as a “rescue action.” Ten rules, “Vow of Chastity,” written by the Dogme 95, act as a guide in their artistic and filmmaking endeavour. On Nigerian soil are the S16 collective: C.J ‘Fiery’ Obasi, Abba T. Makama, and Michael Omonua. Inspired by the Dogme 95 movement, they founded, in 2016, The Surreal16 Collective. This collective, in its almost-a-decade existence, had disrupted conventional industry patterns in its storytelling. It also forged a unique identity for Nigerian films in the international film community. And aside from their admirable achievement, these filmmakers are, through the S16 annual film festival, subtly giving confidence to young Nigerian filmmakers not to boycott their dreams but follow them passionately.

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo’s essay introduced me to the potential of the S16 Film Festival for Nigerian cinema and ambitious filmmakers. But, attending the S16 Film Festival, in person, and witnessing the range of highly artistic and experimental films, as well as the cult–like followership these filmmakers enjoy, I knew writing this essay was inevitable. Watching the range of films screened by these obscure indie filmmakers, at the S16 Film Festival, it’s easier to know that behind the camera are artists, not the usual businessmen. The unusual ambition of these filmmakers, though dented with observable mistakes, are necessary for a large industry such as Nollywood.

Wilfred Okiche, a Nigerian film critic with an attractive international publication portfolio, gave an insightful pointer. “Art house and indie cinema are indispensable to building cinema or film culture here in Nigeria,” he says. “It is usually the breeding ground for a lot of bright, unheralded talents and ideas that are seeking expression before they are corrupted or diluted by the forces of studio or market demands. Also, it takes film culture down to the grassroots.”

Filmmaking across different cultures is mostly focused on its domestic audience – it always looks inside; not outside. Nollywod production has a portfolio for its focus on the domestic audience. Though, artificially, this paradigm is changing, gradually. With the enthusiastic partnership from Netflix, Amazon, and Showmax, in recent years, a certain sense of excellence has been embedded and it has made, at the least, Nigerian mainstream filmmakers care for international attention. Filmmakers’ swift showing of the top position their film earned on streaming platforms, is a pointer to this. Write negative responses about supposedly blockbuster movies, and the creators are quick to share a list of countries their films are topping its list. These box office returns and the obsession of filmmakers with them, aptly convey the obsession of the filmmakers: box office return is the mantra. Nigerian films top the list but barely will you hear of mainstream Nigerian films in reputable regional or international festivals. Though Nigerian names (Chinonye Chukwu and Akinola Davies Jr.), before the S16 collective, have competed and won at Sundance, the filmmakers’ kinship with Nigeria and affinity with Nollywood is debatable.

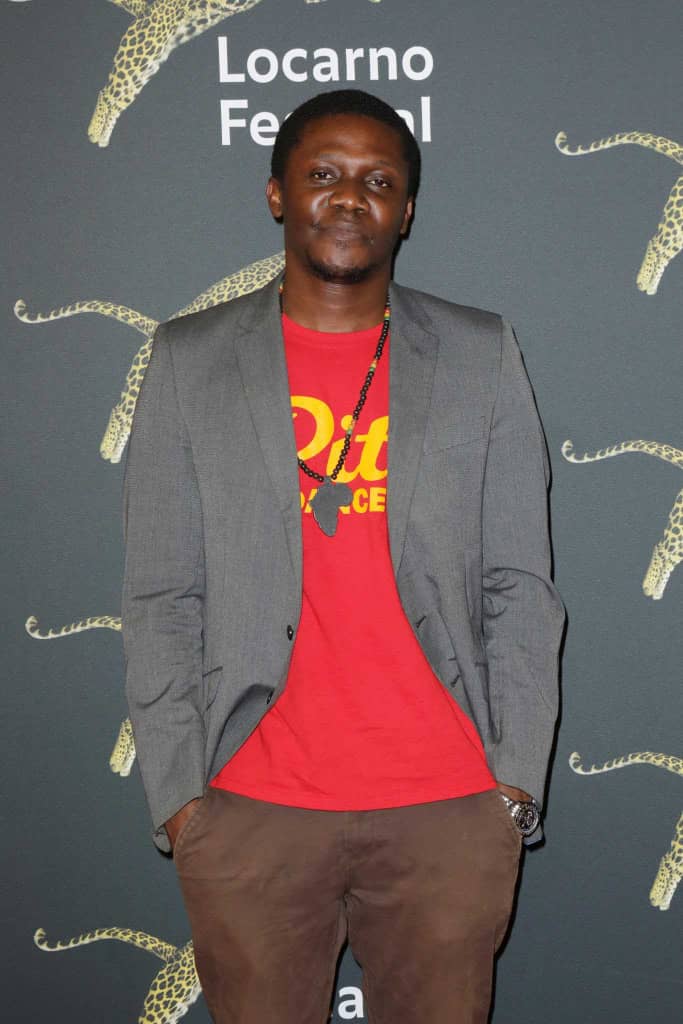

While conversing with Michael Omonua, one of the trio from the S16 collective, at the S16 Film Festival, he hinted at the industry sobriquet they, the collective, have been given — “Festival filmmakers.” A glance through their portfolio, and one is privy to the validity of the label. Through this short-lived conversation, Omonua hinted at how Nigerian filmmakers aren’t tapping into the resources of International festivals. Berlin, Venice, and Cannes still retain their position as the most sought-after film festivals for fiction films. Despite filmmakers’ covetous attempts from different film cultures to enter these festivals, Nollywood cares less. Sadly, Nollywood’s attention has been monopolised by glamour and box-office returns. There came indie and art-house filmmakers: The C.J. ‘ Fiery’ Obasi-directed and Film-one distributed Mami Wata premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, the first Nigerian-bred filmmaker to achieve this.

Patience is a virtue, and these indie and art-house filmmakers are its custodians. Nollywood has a global recognition of being the most prolific film industry. This is a position it contends with Bollywood. This constant obsession with being on the loop with films that lack artistic depth is tiring. Even when Nollywood filmmakers intimate audiences with years spent from the pre-production stage to the distribution stage, the depth of the story often disagrees with its maker’s statement. The efforts we see on-screen don’t often match the years spent during the filmmaking cycle. Obasi had constantly mentioned the seven years it took to make his black-and-white film. Seeing the film’s trailer and the acceptance it has attracted in the international community, the years put into it shown.

Lists, like the one curated by Sight and Sound, are the subtle way of establishing a canon. List asides, the awards and favourable or negative reviews a film acquires also have their way of making films and its makers canonised. Juju Stories, made by the S16 trio, had received a positive review from the New York Times; Chuko and Arie Esiri’s Eyimofe has attracted awards at festival circuits; Akinola Davies Jr, Lizard’s had won at Sundance. Although Akinola’s affinity with Nollywood is debatable judging that he was bred in the West. Damilola Orimogunje’s For Maria Ebun Pataki is a uncommon story; Michael Omonua’s The Rehearsal aside winning an Oscars qualifying competition, hinted at Brutus Richard’s range as an actor. These filmmakers, by treading unorthodox pathways, are creating a distinct pattern for the industry, and curating a canon for Nigerian cinema in the international community.

Aside from giving Nigerian cinema international recognition, these filmmakers are upholding the tenet of democracy — the right to choose. Indie filmmakers have a forte for being alternative cinemas. In breaking the monopoly of mainstream filmmakers, these indie filmmakers give Nigerian audiences, critics, and other filmmakers alternatives. The ability of filmmakers to explore untried genres and give the audience a range of experiences is blissful. These films, in exploring personal stories and unusual stories, spotlighting obscure but talented casts, and treading a rarely seen theme in Nigerian cinema, allow for range in Nigerian cinema. In challenging the dictatorship of mainstream filmmakers, indie filmmakers are conduits of untold, forgotten, and ignored stories.

Jerry Chiemeke, the Nigerian film critic who will be covering the Berlinale, gave a lengthy but important comment. “It (art-house cinema) is important for documentation. Every industry needs that sort of film in curating its evolution as an industry. When you look at streaming platforms, cinematic releases, you find situations where the only thing you have preference to are rom-com, slapstick comedies. It is important to have a mix of different genres and body of work; you want to have a well-rounded industry you can make reference to not just when pitching to investors but also in the next 10 to 20 years when you are curating and documenting the history of Nollywood.”

“Beyond documentation, there is the need for diversification purposes for audiences, critics and even filmmakers seeking for inspirations to have a range of options to pick from. Art house cinema movies may or may not tail the box office. But, they exist for a reason. Beyond storytelling that helps in providing perspectives for both audiences and filmmakers, it’s also a place to point at and draw inspiration from. It is a vehicle via which filmmakers can tell personal stories and experiment,” Chiemeke concluded.

Can one confidently say mainstream Nigerian filmmakers are uneducated of the potential festivals portend to the industry or that they don’t know the benefits — at least the umbrage about an Oscars submission show? Are the financial obligations to make those aspirations come to pass making the filmmakers apathetic to these festivals? Or is the apathy enhanced by politics, the self-righteous need of our filmmakers to maintain dignity of “our story and culture” without toning it down for Western validation? Or is the financial obligation of a festival campaign a reason for this distance from festivals? Is it sheer ignorance?

Martin Chukwu, the convener of the annual The Annual Film Mischief (TAFM), started the TAFM festival because he was an indie filmmaker himself. He was concerned about celebrating and validating the horde of styles and talents that abounded in low–budget and indie filmmaking. TAFM being one of the go-to film festivals for indie filmmakers, “It was important to showcase unique voices and filmmakers with very broad sensibilities to film and cinema. TAFM is a place to encourage and inspire new voices to know that (even when it is hard to build an audience for indie films) a place exists for them where they can be seen.”

“The indie filmmaker is passionate to tell stories in a different way, ways that the mainstream players won’t because of their economic policies. They won’t touch some stories, not because they don’t like them but because they are not ready to take that risk,” Chukwu concluded.

To create a uniquely independent voice, and forge a different path for themselves rather than follow the industry pattern, these indie and art-house filmmakers are gradually building an audience for themselves. And although their endeavours are often solitary, encouraged by few friends and minimal funding, these filmmakers and their films are creating a distinct blueprint for ambitious Nigerian filmmakers and the Nigerian film culture.

Seyi Lasisi is a Nigerian student with an obsessive interest in Nigerian and African films as an art form. His film criticism aspires to engage the subtle and obvious politics, sentiments, and opinions of the filmmaker to see how it aligns with reality. He tweets @SeyiVortex. Email: seyi.lasisi@afrocritik.com.