People are going to try to do something like Mami Wata. People are going to try and delve more into their own mythologies and their spirituality. Especially in Nigeria, there’s going to be a pre-Mami Wata and post-Mami Wata era. That’s a guarantee. And, for me, it’s a good thing. – C.J. Obasi

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku, Helena Olori, and Blessing Chinwendu Nwankwo

There has never been a better time to tell African stories. From the arrival of Afrobeats and Amapiano into global music conversation, to African films winning major awards on the global film festival circuit and raking in massive audiences on streaming platforms, African creators now have greater access to the global stage than ever. But as Spiderman’s Uncle Ben famously said, “with great opportunity comes great responsibility.” We are living in a delicate era of African representation. And the foundations we lay during this period of sunshine may very well shape how the world sees Africa, for better or for worse. Especially since the pen is finally in our own hands.

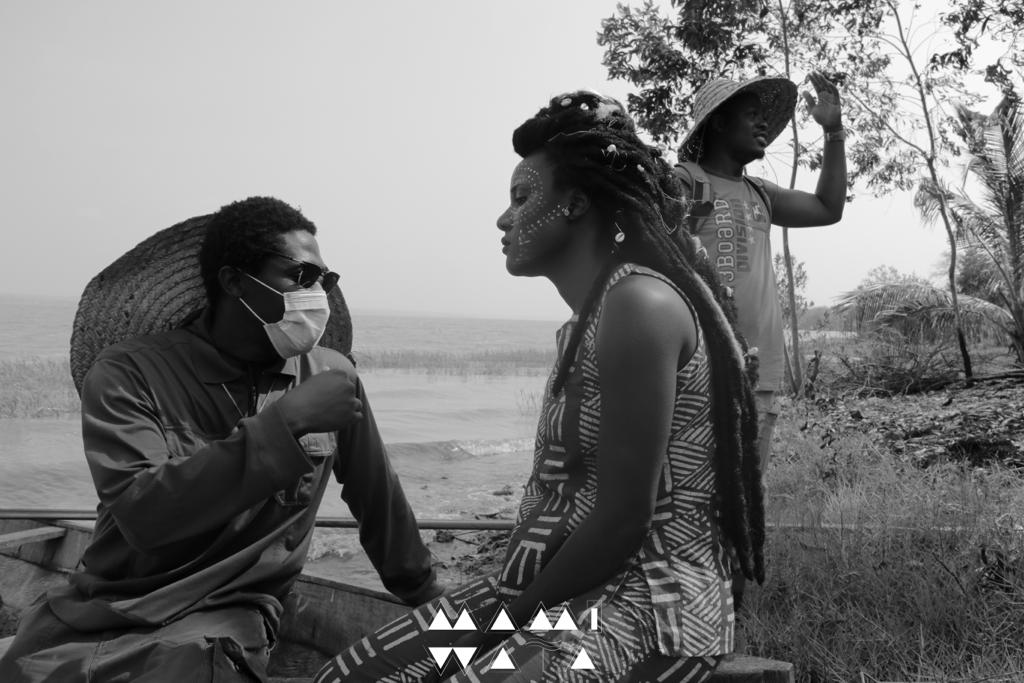

It is this understanding that drives us at Afrocritik — projecting Africa, one story at a time, highlighting her diversity, and participating in the painting of that new portrait of our continent. We were, of course, excited to discover Mami Wata, a West African folklore fantasy film about two sisters fighting to save their people from external forces and to restore the glory of Mami Wata, a water goddess, to their land.

Since Mami Wata wrapped production in January 2021, it’s been good news after good news for the C.J. Obasi-directed feature, produced under the banner of Fiery Film Company. Founded by C.J. “Fiery” Obasi and Oge Obasi, to create genre films from an African perspective, Fiery Film is no newcomer to the film festival circuit. From Ojuju, their zero-budget zombie feature film, to Juju Stories, their anthology film with the Surreal16 Collective, their previous films have enjoyed multiple festival screenings worldwide and won several awards.

But Mami Wata is reaching new heights. The biggest news so far is the film’s outing at Sundance, where it premiered in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition and clinched a Special Jury Award for Cinematography. Before then, Mami Wata had been selected to participate in the Final Cut at the Venice Film Festival in 2021. After Sundance, the feature had its African premiere at the Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) where it won the African Critics Award, Best Image (Cinematography) Award, and Best Decor (Production Design) Award. It has also landed multiple distribution deals, from African distribution by FilmOne, to international distribution by Paris-based Alief, North American distribution by the New York-based Dekanalog, and more recently, a U.K. distribution deal with Aya films.

Mami Wata is still travelling the world, but in-between all the screenings and wins, Afrocritik caught up with the film’s writer-director, C.J. Obasi, the producer, Oge Obasi, and Lílis Soares, the Brazilian cinematographer, who won the film its Sundance award. In this exclusive interview, the Mami Wata trio talk about Sundance, the representation of African women, the highs and lows of creating Mami Wata, and what inspires them.

Note: The following interview has been edited for length, style and clarity.

Congratulations on the success of Mami Wata, especially the Sundance win. Film festivals are not new to you, but how did it feel to get to Sundance?

Oge Obasi: Well, film festivals are not new, but Sundance is Sundance, right? I’m still processing. I mean, the work is still ongoing. I don’t think I’ve really sat down to take it all in, because this is a ten-year journey for me and C.J., and a seven-year journey for the film itself. So, it’s kind of surreal being at the place that you have projected to be for years. It’s like that dream coming true while you’re awake. It’s really exciting. It’s really encouraging, because the path we took is not one that most filmmakers will take in Nigeria. And it came with its own sacrifices, being on a path where you’re saying, “This is what we want to achieve,” and nobody believes you or understands.

C.J. Obasi: It was literally a dream come true. I used to dream about being at Sundance for as long as I wanted to make films. And when I conceived Mami Wata, my desire was for a Sundance premiere. Being there in Park City, Utah, premiering a film we worked on for seven years, with my team — my family beside me, there are just no words to describe that feeling. It was pure bliss. There’s nothing like Sundance, and I’ve been to a lot of amazing film festivals.

Lílis Soares: Honoured. I’m so honoured. For me, Mami Wata is a gift from God, from the universe. I received a gift when I read the script. Because all of my life, I have wanted to shoot something like this. It’s about my study, my aesthetics, my history, and ancestrality. It represents many things for me, and I put my body, heart, and soul into it because it is very important for me. Even if I didn’t get the Sundance or any other awards, Mami Wata would still be that important to me.

Before we get into Mami Wata, can you tell us a bit about your background and what inspired you to go into filmmaking?

Lílis Soares: Growing up, I had interest in imagery and representation in cinema. I remember asking my mother for a camera, but she gave me one that wasn’t so cool. But my brother had a good one, and every time I touched this equipment, it was like magic.

I studied audiovisual/cinema in Brazil in the early 2000s, and later cinematography in France because it was very important to my work. That’s when I realised there was a problem with Black representation. Cinematography here [in Brazil] was always about white people. I am an Afro-Brazilian woman and cinematographer; with all of the means and things it represents. I am very passionate about the Black race and people of colour, especially here in Brazil. This has influenced my work significantly because I am very concerned about Black, women, and minority representation in the aesthetics of my work and creating new narratives for Black people. My works are just another opportunity to bring visibility to women and people of colour here.

C.J. Obasi: I had a fantastic childhood. I’m the last in a family of five. We used to be seven, then I lost my two elder sisters who were much older […] and were like my parents. In a lot of ways, they raised me. And I would come to understand that being raised by my sisters also helped influence the kind of stories I make, as I’m always trying to honour them one way or the other. That mindset came together the most in making Mami Wata — in making these very complex, strong, nuanced African women that I haven’t seen before but I’ve always known in my life. But growing up specifically in Owerri was a huge influence. It used to be this small town but also very education-driven. Reading was a way of life, so I grew up reading a lot of books from the Chinua Achebes to the Stephen Kings, the Tolkiens, the Salingers. On one end, I had that, but on another end, I also had a very traditional upbringing that highlighted the Igbo tradition. But it never took away learning about other cultures.

Oge Obasi: There’s nothing much about my background. I was just a regular kid, a bookworm. I’m an only child, so I didn’t have the interesting, boisterous upbringing full of adventure. I read my own adventure.

Did you always know you would be a filmmaker?

C.J. Obasi: To a degree, because film was my love. The earliest memory I have is a movie. The movie that activated my memory is Evil Dead by Sam Raimi. I was barely three or four, and it changed my life. I wanted to see more movies. And all of that were the birthing seeds to the kinds of stories I later on started to tell. Even though those were mostly western stories, what I remember was always drawing parallels between those stories with the world that I came up in. And as I got older, I became more of a student of cinema and a student of culture. It’s always about how to merge that cinematic sensibility with my understanding of culture into something new and something that I haven’t seen before.

Oge Obasi: Filmmaking, I’ll say production generally, found me. I didn’t start with film, but I had some time in reality shows and music videos. I was looking for something else. I pretty much walked into a set, and it was intriguing for me. Before then, I was somebody who knew something about most things I come across, especially being a vast reader. But production was the first thing I came into and didn’t know what was going on. Like, “who are all these people?” “What are they doing?” That caught my attention, and so, I would just work anywhere there was a production. Don’t pay me, no problem. I did that for a while, and from there, I started getting proper jobs. My first film experience was The Figurine in 2009. Then, in 2013, we shot Ojuju. So, it’s been quite a journey.

As female filmmakers, and women of colour, how have you navigated the unique challenges of your professions?

Lílis Soares: It’s hard. In Brazil, despite that half the population is black, it was not normal to see women like me in front of the camera or “manning” it. To be here, doing my work amidst the racism and sexism, is not easy. Even with the awards, which are huge for me, and the Brazilian cinematography history, the marginalisation is still there. Everywhere I have gone to study, in Brazil or France, I was the minority. But I reckon if I do not work and make a name for myself, nobody would help me either. That’s why I am always ready, when the opportunities come, even with the lack of equipment. I take it and try, and if it doesn’t work, at least I tried. So, every time I pick up the camera, I put myself up for a big challenge. And my family, they keep me going with their unwavering support. They trust my abilities and skills, and they keep pushing me on. My mum, especially; she helps manage everything.

Oge Obasi: In my early days, when I worked as a production assistant, people used to be very sceptical about hiring me. They wanted boys for the job. And then, I looked like a nerd; it didn’t help. It was even really hard getting the jobs that I wanted to do for free. And then, equipment were much heavier than they are today. I had to pull my weight, and I didn’t mind, because I could handle it even though I didn’t look like I could. It was exciting for me learning a lot of things I didn’t know how to do and shocking people that I could do the things that I could do. I just found my home there. And by the time I partnered with C.J., that also came with quite heightened expectations and challenges, of course. A lot of hard work.

Let’s talk about your partnership: working with your spouse and building a sort of indie empire. How are you navigating differences in ideas and techniques?

Oge Obasi: It’s never been a struggle. Our jobs don’t interfere with each other. We are working towards a collective goal, and we also have our unique strengths. Because there’s always been a common goal and we never lost sight of that, it’s been quite easy to go through those phases, to just survive through to the next thing and to also not really have conflict in ideologies because we know where we want to go. We have our individuality as well as the partnership.

C.J. Obasi: I guess it really boils down to two people who respect the hell out of each other. We respect and honour our individual strengths and weaknesses. It’s art, but it’s also a business. And we have a clear vision of where we would like to take the art and the business. But more so, I think she’s the best producer in the world. She thinks I’m the best writer-director in the world. It doesn’t have to be true for others, but it’s certainly true for us. And that’s all that matters.

Let’s circle back to Mami Wata. It’s being marketed as a West African folktale, filmed in Benin Republic, even though the producer, the director, and the majority of the lead cast are Nigerians. How much of the story was drawn from non-Nigerian West African influences?

C.J. Obasi: It was drawn from all over, and that’s the point of the film. The whole thing was not envisioned as a purely Nigerian story. The root of it is West African, which is why it’s called a West African folklore. You know, they have something like that in Brazil. What they have is still rooted in West African folklore. And it’s the connection that runs through the rest of West Africa to other parts of Africa and beyond, the diaspora. I remember when we were pitching it in Ouaga Film Lab, the people in Burkina Faso and other people from Senegal, from Ivory Coast, came to us to tell us how meaningful the project is since they have their own experience of Mami Wata. But what I’ve always found interesting is that despite how diverse Africa, West Africa especially is, you still have people referring to this deity as Mami Wata. Of course, within the tribes and the ethnicities, they all have a name for the water deity or the water goddess. But despite all of these, everybody recognises Mami Wata. It was all of these experiences and the understanding of these realities that made me know this is not just limited to Nigeria, and I have to tell a story that kind of encapsulates the texture of West Africa.

What informed the choice of location?

Oge Obasi: We didn’t intend to shoot in Benin Republic at first. We were going for Gambia, but then COVID-19 happened and travel became very expensive. At that time, we hadn’t been able to raise money through the European funds and institutions that we had hoped we would raise money from. And I absolutely didn’t want to wait anymore to make the film. We had to start making changes, and one of them was location. Try as we did, we couldn’t find locations in Nigeria, at least in the places that had coastal areas, that were safe to go to. The beaches that were well-handled or maintained were also like tourist centres or zones, so a lot of structures had been put there. We were going for an untouched look, a place that has not been touched too much by civilisation. All the while, it wasn’t like one didn’t think of Benin Republic. It’s just the concern about the language factor. Eventually, we decided to just go in. And it worked out very well. It was very conducive for us. It was eye-opening. The energy was really good for us and, even though we had a lot of challenges, it helped everyone to find some peace. The people were welcoming, too.

You also stepped out of Nigeria to recruit your Director of Photography, Lílis Soares — a great choice, seeing as she won the film its Sundance award. But why Lílis Soares, and how did you get her onboard?

Oge Obasi: We were making a female-driven film, so C.J. specifically wanted a female cinematographer to balance what he calls the male gaze. Then, we didn’t just want somebody because she’s female; we needed a badass cinematographer. Basically, for the film, there’s no reference. There’s no film you can say, “It’s like this film.” Where are you going to see that highly contrasted black and white film, which was what we were going for? We needed someone who was not only absolutely fabulous at the job, but also a female and, hopefully, a woman of colour. It took us over a year because we also wanted someone who the film would mean something personal to. It wasn’t easy to find.

Those are a lot of requirements.

Oge Obasi: But that’s how we’ve always worked. Everything has always been intentional. The choice of project, the approach to the project. Lílis says when she got the email from C.J., she thought it was spam, because the timing was so ridiculously exact. She had found out that she comes from a lineage of Orisha-worshipping women, and so she had gone down that road of reflection and introspection when the email came. What type of coincidence was that? And in that email, C.J. really poured his heart. That’s how we connected. She’s fantastic. I look forward to doing more stuff with her. There’s nothing sweet for me as a producer like knowing that you don’t have to be micromanaging anybody. You can rest assured that as planned and as agreed, the work is happening. Finding the right people to collaborate with makes all the difference.

Lílis Soares: I was on set shooting when I got the email, and I thought it was spam. I have always wanted to work with African directors because I love African cinema and the representation, the ancestrality and the connection we share, and I hoped maybe we could create something together. So, when I received the email, it was a dream come true, and I couldn’t believe it. I had to show it to a friend, and she encouraged me to follow up with it. I later learned that a woman in Norway had recommended me to Obasi, and I didn’t know the person. It felt like the universe orchestrated it. And when I read the script, I loved it, it was amazing. Till today, it’s one of the best scripts I have read. Shooting the film was more than just filmmaking for me. It was about my religion and its representation. My religion — Candomblé — has its origin in Nigeria and Benin. I feel so connected with this project, and it was an opportunity to passionately showcase my beliefs. Here in Brazil, they have tried to violently erase our roots in Africa. Having this project was like rewriting history.

Mami Wata was shot in black and white, a rarity on Nigerian screens and everywhere else, really. Why did you opt for that style?

C.J. Obasi: Black and white TV is something that comes from a very specific time, and growing up, that was the only way I could watch movies. I have a very sentimental attachment to black and white, and how it takes me back to a time. That feeling is what I tried to capture with Mami Wata. Then, there’s the spiritual reason, which is how I received the vision, and that’s what I wanted to continue in. But also, there was a more strategic reason. Everything is content now in this world. You make a good movie, and your movie, no matter how good it is, is going to compete with a TikTok video, because it is the same audience. Even great work is getting missing in all the noise. So, I wanted a film that stood out, without even trying. It just stood out on its own, visually, before you even get into the storytelling and find out if it’s good or you like it. I just wanted something that aesthetically stood out. When I started having the first conversations with Lílis, I was like, “Look, I want to make the most stunning film anyone has ever seen, whether it’s from Africa or anywhere.” And that’s what we set out to do. So, even if anybody doesn’t end up liking the film, what you’ll never deny is that, visually, you’ve never seen anything like it. And that has been the case. Every single review of the film talks about the vision, talks about how it stands out. I think there was a reporter on CNN that said that if there’s a better-looking film at Sundance, he’ll eat his laptop.

As the cinematographer and the eyes of the director and producer, were there any reservations you had with respect to the style?

Lílis Soares: No, I didn’t have reservations doing it. When there’s a close viewpoint of what the story, cinematography and aesthetics should be, it becomes easier to create what needs to be achieved. Prior to this, I had never seen movies like this in black and white, especially for Black people, so it was difficult to find something to reference. But C.J. and I talked and shared common ideas about each scene and its meaning in the bigger picture of the film. Although it required a lot of techniques working in shades of grey, by the time we shot the first three scenes, it was a classic. There were times we tried to create something and it didn’t work, but I had a team that believed me, and kudos to them, we were able to pull it off.

It’s particularly interesting that the film was shot principally at night. That must have been quite daunting. What was the experience like, the challenges, and how did you achieve your goals?

Lílis Soares: The film is mostly a dark picture film, and I knew we needed that darkness to achieve the picture in mind. While I would have liked it better if we had more lighting, it was also about my ability and techniques in handling the available equipment. For many scenes, we worked mostly with the body movements of the actors who were also very fantastic. My experience working with black-skinned people was of great advantage here as well. For me, it was like painting. I just needed to know where to put the light and where to add volume. It was just a matter of lighting and exploring different angles to achieve it.

C.J. Obasi: If you’re shooting in black and white and all your actors are dark-skinned, you’re already running into some challenges, because there’s already a lot of challenges that come with lighting dark skin. First of all, dark skin is a storytelling tool in Mami Wata ’cause we wanted to make dark skin look gorgeous. So, it means that we have to put dark skin in the centre of our story. The way to do that is to capture it in the most glorious light. And the best way to make dark skin look glorious is to shoot dark skin during the day because then you can see it in contrast to the light. But we went even further in Mami Wata and made sure that we shot dark skin, a lot of our scenes, at night. And as far as filmmaking goes, that is almost like an unwritten rule that you don’t do. You don’t shoot dark-skinned people against the night. They will just blend in. But we did that with Mami Wata. In fact, a lot of the scenes originally written to be shot in the day, I changed them to night deliberately, to say to hell with that rule. But it comes with a lot of challenges. You have to be very intentional. We had scenes that were like thirty seconds long, but we would spend hours setting it up and lighting it.

Were there other challenges that came up while shooting Mami Wata?

Oge Obasi: Yes, almost all of it came from Nigeria. It was ironic. I’m not saying that to put Nigeria down. We were making a film about Mami Wata. Typically, in Nigeria, we got a lot of “God forbid. Are you people Christians? Don’t you believe in God?” Then, the first time we took Mami Wata out of Nigeria, it was to Burkina Faso for a film lab, and they were like, “Oh, thank you for telling this story… Oh, I’m so happy you young people are thinking like this… Oh, Africa needs this film.” In Benin, all they cared about was that you’re not demonising Mami Wata.

C.J. Obasi: Challenges came with the fact that I wanted to make a black and white film and people didn’t want a black and white film. Even friends told me how much of a terrible idea it was to make the film in black and white. But thank goodness I’m a very stubborn person, so I didn’t listen. On the production design side, there’s a lot of other challenges that come with that. I’m the production designer of the film, and it’s not because I’m a production designer. It’s just because I felt like I needed to be for this film. There’s no precedent for the film. I like to think that I’m good at explaining things, but there’s only so much you can explain if there’s nothing you can use as a reference. Even with the costume. I’m not the costume designer, but I had a bible that said exactly what I wanted for each character to wear, how I wanted it to look, the colour, the fabric, even going as far as designing the symbols on the fabrics so that the costume designer would take them and translate them. We made our own fabric. We didn’t want to use anything like Ankara or Hollandaise, mainly because of the political message of the film. You’re making a movie about a village in West Africa that is rooted in culture and you’re using fabric that is made in Holland. I didn’t want to fool anybody, but I also didn’t want to fool myself. So, I went as far as getting the fabric that came from Nigeria, from a village in south eastern Nigeria and from Badagry, just to make sure that it was true to the root of the West African story.

Lílis Soares: Production challenges? Well, one major challenge was the fact that we shot during the COVID crisis, and that affected the logistics a lot. Specifically, for my work, we had limitations with equipment. I would have loved to have more lighting.

Oge Obasi: I had an equipment partner whom we had gone into contract with. When we now said, “We’re ready. Send equipment,” it was radio silence. After about five days, the man says, “In short, I’m not doing again.” Just like that. Because we were going for a particular look, we couldn’t film with just anything. And we needed loads of light, which needed loads of generators. We needed specific lenses. Where do you start from? The advice, generally, was to shut down the set and go home, and then plan again. I said no. And we kept trying […] to rent equipment with cash. You go somewhere and they’ve already heard of you or the project, and they say, “We’re not giving you equipment.” We lost three weeks to this, and eventually, we were able to get someone to rent us equipment — a third party made the connection; they are called StartUps Media. But why would people who didn’t know you before not want to rent equipment? There are times you’ll send your equipment list, and somebody says, “I’ve seen this list before now, is it that Mami Wata?” “How do you know? We’ve never spoken before.”

Was it the nature of the film that caused the challenge, then?

Oge Obasi: No, it was a gang up. Sorry to say. At that point, it seemed like a ridiculous thing to be thinking. But at some point, things emerged that indicated that it was actually intentional by mischievous people. When someone says to me, “Do you think you had challenges because Mami Wata was upset with you?” I say no. If anything, I think Mami Wata was happy because we got very unique kinds of solutions in some kinds of unique situations.

C.J. Obasi: Thankfully, my wife, Oge, is like the best producer in the world. For a shoot that was supposed to last for six weeks, she managed to make it happen under four. But, of course, if you are planning to shoot for six weeks and you end up shooting four weeks, that’s going to take a toll on everyone.

When we see Africans on the global screen, they’re predominantly foreign films. So, as an African-made femicentric film, how does Mami Wata add to the conversation on diversity and representation of Africa and African women globally?

C.J. Obasi: I mentioned my inspiration in drawing from my late sisters and trying to pay homage to them, to remember them and to see people that reflect them on the screen, ‘cause I haven’t seen that anywhere, whether it’s films by westerners or films by even Africans. When you watch Mami Wata, even though it’s a movie set in a rural part of West Africa, it doesn’t feel like your usual rural African-set film. First of all, everyone looks like God. Because that’s how I see us. And it’s political, because it’s what the West has over us. The way they capture themselves ends up being how we see them versus how we see ourselves. What if, instead of showing you the symbol of a white-skinned Jesus Christ, I show you a symbol of a dark-skinned mermaid goddess that is filmed with the same level of glory that you see in that white statue? What does that do for the African girl child who sees that?

Oge Obasi: A lot of times, I watch movies, but I don’t connect with the women I see. A lot of women are conflicted because you know you have this inner power in you, but you’re also told to suppress it so it doesn’t look like you have it. It’s that power that women use that I really want to explore more and share more with the audience. Mami Wata is a Black woman. We have to own that narrative. She’s a goddess of fertility, of progress. When people talk about Sango, Amadioha, all the rest, people are like, “That’ll be cool. Those movies will be interesting.” But when you mention Mami Wata, they say, “God forbid.”

If so many people believed in her in West Africa for such a long time, she must really have mattered.

Oge Obasi: In the Caribbeans, too. Even in Brazil. Those cultures are still alive. It’s not even like a fantasy. Hollywood will create Little Mermaid, and people will rush and go and watch. You’ll buy all the merchandise. Then you’ll say, “God forbid Mami Wata.”

Lílis Soares: For us in Brazil, we have a day to celebrate “Iemanjá,” (in English, Yemanjá) that is like Mami Wata. But Yemanjá is represented as a White woman here. So, creating Mami Wata was an opportunity to collaborate with other Africans to properly represent her and bring visibility to our culture. It’s very important to have more African directors create real African stories because the problem is that till now, there are many African stories in Hollywood that do not accurately represent our histories and cultures as they are. And we can’t change this if we do not have voices. Having more African filmmakers will increase the conversation on diversity, give us the opportunity to make our own mistakes and improve on our art. Mami Wata is an example of what potential African cinema has, but we need more films like this.

The highly-anticipated Nigerian premiere date was recently announced. What would you say Nigerian filmgoers should expect from Mami Wata?

C.J. Obasi: They should expect a pure and sincere expression of cinema; a truly immersive and cinematic experience. These are things I’m offering Nigerian cinema-goers, which is not a mean thing. This is not to bash anyone, but Nigerian films rarely give you that immersive cinematic feeling. The Nigerian audience has to go to Hollywood films for that. Mami Wata will give the audience that experience, visually and sonically. And I think that’s what makes Mami Wata worth experiencing in the cinema. Mami Wata has the best sound for any Nigerian film you’ve ever watched. It’s brilliant. The artistic design of the sound. When you’re sitting in that room, you’ll literally feel like the ocean is washing all over you. Like you’re immersed. We have a beautiful score, and the music just serenades you. It just feels like this is a cinematic offering that was made for you to enjoy in the theatre.

Lílis Soares: When I saw the first image of Mami Wata, it was like magic. I hope that’s the experience for the audience as well. I really hope that people will see this movie and feel something different, especially for Black women. It’s not just about a movie, but an African artistic movement for Africa and diaspora. Aesthetics are politics.

Oge Obasi: For me, it’s more from a story perspective, and how they relate with that story. It’s not necessarily from the other artistic part. If it stimulates and tickles them, all fine and good; we’re making progress. But for me, it’s majorly from how they react to the representation of us as Africans in a fictional village. The important thing is not what I say to them; the important thing is getting them to come see it. After they see the movie, they can now decide what they think about it.

Do you think Mami Wata’s achievements can influence how the international industry receives African films going forward, and do you think it will impact Nigerian and African filmmaking?

C.J. Obasi: Oh, it’s already happening. People are going to try to do something like Mami Wata. People are going to try and delve more into their own mythologies and their spirituality. Especially in Nigeria, there’s going to be a pre-Mami Wata and post-Mami Wata era. That’s a guarantee. And, for me, it’s a good thing. For every festival the movie has been selected in, all the programmers, all the artistic directors that select the film always talk about how this is a fresh vision of Africa. And that, for me, is the win. When they see Mami Wata, they say they’ve never seen anything like it before. It’s about a new vision, it’s about a new way of seeing Africa. It’s about a new aesthetic. Like my cinematographer always says, aesthetics are political, because aesthetics are associated with a mindset, with a stereotype, with an imagery of a people. And so, as long as you can reinvent that successfully, you have reinvented how people see a particular people. And that, for me, is the success of Mami Wata on a global stage.

Lílis Soares: As a cinematographer, I have in my hands an incredible opportunity to visit my roots and explore black and diasporic aesthetic codes in depth. We can use this position to change realities, to create another gaze and narratives. This is not new. Our ancestors did this in religion, music, and fashion. We use the language of the cinema to bring awareness to the African and afro-diasporic representation and history. Aesthetics are politics. And I hope Mami Wata will become a reference point in African filmmaking, especially for its daring aesthetics. We need to strive to see that what we’re doing is not just reproduction but diverse storytelling about Africa. If we want to make a difference in the industry, we must dare. Mami Wata is a daring movie, and I hope this film pushes more filmmakers to create new narratives, not by American or European standards alone, but deeper than we did were before.

Oge Obasi: A lot of filmmakers are conflicted between making films that the Nigerian distribution will be comfortable distributing and making the kind of films that they truly want to do. The streamers that are here now, we prayed for it for so many years. And then, they’ve come, but our films have not really changed in terms of storytelling boldness. We keep relying on a Nigerian audience worldwide or Africans in diaspora, whereas we’re supposed to be making films that, globally, can be consumed irrespective of where you’re from, the way we, too, consume films from other regions irrespective of where they come from. Opportunity will come. The audience is there. But we, filmmakers, are we ready? Are we taking advantage? Also, as much as the world is ready for African stories and we may still be finding our voices, especially regarding Nigerian cinema, I would really like to encourage filmmakers to collaborate and co-produce, especially with other African filmmakers. There is so much we can learn from one another, and together, we have a stronger voice.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku, a film critic, writer and lawyer, currently writes from Lagos. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv and Instagram @_vivian.nneka.

Helena Olori is a talented multimedia journalist, she enjoys staying abreast with latest happenings in the film industry and what makes the movie business tick. Connect with her on Instagram @heleena_olori or helena.olori@afrocritik

Blessing Chinwendu Nwankwo, a film critic, beautician, and accountant, currently writes from Lagos State, Nigeria. Connect with her on Twitter at @Glowup_by_Bee and on Instagram at @blackgirl_bee.