Aiwanose Odafen’s novel has entered popular feminist discourse, calling our attention once again to the travails of women. One realises that this is a topic that can never be truly exhausted…

By Chimezie Chika

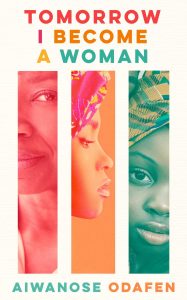

The first few pages of Aiwanose Odafen’s Tomorrow I Become a Woman certainly prepares one for what is to come; yet one is never fully prepared for the level of depth with which abusive marriage is treated in the novel. The novel excavates every aspect of a dysfunctional marriage with a deceptive simplicity. We see it from all angles, and we also view the slow atrophy of love and attention. Perhaps, here, we learn a lesson or two about why young Africans today are taking longer to make decisions about marriage.

Tomorrow I Become a Woman follows its protagonist, Uju, whose dreams are muted by her desire to please her mother. This desire would lead her to make decisions she would ultimately regret later. On the cusp of graduation from the University, Uju marries Gozie, a handsome man she met in her friends’ church, even though she is not certain of her love for him. This would be Uju’s greatest hubris: her inability to make firm decisions until someone else pushes her into it. What follows in Uju’s marriage to Gozie would lead us to a quiet tragedy of three intertwining lives.

(Read Also: A Call to Greater Understanding: A Review of Ukamaka Olisakwe’s Ogadimma, or Everything Will be Alright)

Perhaps the most dominant character in the novel is Uju’s mother, Mama, but she is not a very likeable one, and even when the author explores the pathos of her grief at the loss of her brother during the Nigeria-Biafra War, the reader struggles to develop sympathy for her. Mama’s prodding is entirely detrimental to her daughter, Uju. Mama’s tribalism drives her into not giving enough consideration about the man in her life, Akin, who has hovered in the background of her affections before Gozie appeared.

Uju’s parents’ insistence on her marrying an Igbo is reflective of the Igbo tribal consciousness in the ‘70s and ‘80s Nigeria—partly an emotional residue of the Civil War years earlier. Tomorrow I Become a Woman explores this in detail throughout the story as we begin to see binaries of ethnic relationship shown in all its negative and positive complexities.

Mama is one of those orthodox women who see marriage as the apex of a woman’s life. Uju’s life shows that such rigid orthodoxy is not always the best, with the denigrating belief in a wife’s mute docility and unquestioning subservience. Mama’s domineering presence in Uju’s life can be very difficult to read at tmes. When Uju begins to date Gozie, her mother says to her: “Nne, please behave yourself with him; don’t drive him away. Don’t talk too much, and don’t be doing i-too-know. Even if he is wrong, just smile, at least until he pays your bride price.”

Mama’s definition of womanhood is marriage and childbirth. To this end, a woman must shrink her dreams and aspirations, and must ultimately shrink herself into oblivion in order to achieve that dream of being a woman in an African society. Mama’s every effort is to suppress every attempt by Uju at independence, from her academic dream to even her attempt to rationally consider Gozie’s proposal of marriage. On that occasion, Mama tells her: “Uju, a woman should marry when a man is ready.”

There is so much baggage associated with the word, “woman,” the author seems to say, for at every turn, the mention of the word is a manifestation of discrimination and culturally heavy responsibilities encompassing marriage, childbirth, and other forms of gendered roles. Tomorrow I Become a Woman exposes how certain aspects of culture can be detrimental to the well-being of women. There are women who are disgraced for doing things men do habitually. Uju realises that what is called “culture” today is not really the culture of yesterday.

Indeed, there is an argument that the conversion of groups such as the Igbo to Christianity has adversely affected the traditional cultural values of the Igbo people. The question of what decent dressing entails comes in here, for our forebears revealed quite a fair amount of skin without inciting rape or attracting it. There is also the question of a woman bearing her husband’s surname which, contrary to what many may think today, is not part of Igbo culture and many other indigenous cultures across Africa.

With her religiousness, Mama is quick to blame every intimation of misfortune on invisible enemies. This is partly why her presence in Uju’s life always involves making quick decisions to beat the enemies. In the end, she drives her daughter into despair, for she truly fails to see her true emotions. Mama never blames the man. Every act of violence meted out on Uju is ultimately Uju’s fault. At some point, it becomes almost impossible not to skip the parts of the novel involving Mama, for it often becomes agonisingly painful to read.

With its two-dimensional drawing of Mama’s character, the novel details a time when older women tried to create wives for men through the painstaking training and domestic policing of their daughters. Everything about their daughters—birth, training, school—must be tailored towards a final end: marriage.

Tomorrow I Become a Woman exposes all the micro aggressions against women in excruciating detail. We also learn that there are women who enable patriarchy, such as Mama. Every detail of Uju’s marriage is more acute than the one before. The exploration of a dysfunctional marriage is both cold and emotional in its precision. In this respect, the novel shares kinship with other marriage studies that have begun to appear in Nigerian Literature in recent times. Recent novels exploring the marriage condition include Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me, and Ukamaka Olisakwe’s Ogadimma, or Everything Will Be Alright. But perhaps, more than any other book, Aiwanose Odafen’s novel pays greater homage to Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood.

There is nothing in this novel that hasn’t been explored before. The pattern follows an almost clichéd trajectory. From the travails of marriage, to the horrors of childbirth, to the interference of in-laws, to the evils of patriarchy, down to the unexpected discovery of a love that has always been there. The irony of interference in what should largely be a private marriage is that, while Mama exercises the freewill to interfere in Uju’s marriage as she deems fit, she strongly discourages her sons from doing the same in the event of violence against her daughter.

Mama’s sanctioning of such domestic aggression is astonishing. Mama’s antics in Uju’s marriage is so persistent that the reader even begins to wonder whether she, herself, passed through the same issues as a young woman. For, in fact, there are instances where even Uju exhibits some twisted form of Stockholm’s Syndrome.

(Read Also: Nnamdi Ehirim’s “Prince of Monkeys” Captures the Trauma of a Generation)

The understanding we get from these novels is that marriage is not a paradise of love and eternal bliss. The reality is shocking. The irony appears in one instance when Chinelo, one of Uju’s close friends, assumed that she was missing a lot of good things by not being married at the time her friends did, without knowing the level of violence Uju was enduring. The irony is captured in Uju’s first person narration. “With Ada’s marriage, Chinelo’s singlehood was cast into harsh spotlight, the emptiness of her ring finger glaring beside the perfection of our wedding bands.” Here, there is the ultimate assumption that a woman is incomplete without the imperfect institution of marriage.

Tomorrow I Become a Woman’s infusion of Igbo words is commendable. Though the words are italicised, they are, for most parts, left unexplained. The context explains the words in some cases. But, otherwise, the uninformed reader must make use of their Internet search engine. The author deftly captures Igbo culture in the novel. It is also heartening to observe that the Igbo words and phrases in the novel are spelt correctly.

Told in short chapters, the story does not exactly paint men as angels. Where they appear to be, there’s always a less-than-desirable monstrosity lurking. But there are good men such as Akin, who redeems the image of men in the novel.

Aiwanose Odafen’s Tomorrow I Become a Woman is not an easy read, emotionally. The novel is a treatise on violence, especially domestic. But there are other forms of violence. The violence—spoken and unspoken, forced and unforced, acted and unacted—is everywhere in the story. From the military regimes of the ‘70s and ‘80s to Uju’s personal life. The deliberate recourse to violence in Africa is shocking. A child misbehaves, he is spanked with a rod; a couple is having marital issues, and it degenerates into fisticuffs; the military takes over government, and it immediately starts exerting violence on innocent citizens through a group of sanctioned gestapo. There are even people who encourage violence as a way to correct misdemeanour. Whether or not such measures are effective is up for debate. But this is especially what we see with Uju’s mother in the novel.

Aiwanose Odafen’s novel has entered popular feminist discourse, calling our attention once again to the travails of women. One realises that this is a topic that can never be truly exhausted. The concerns of women in modern society is valid, as this novel makes us see. We realise that the point of womanhood is not a one-dimensional attachment to a man, but a complex network of cultural and societal abuses that must become subject to change. Womanhood thus becomes that moment of change.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Praxis Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment.