The endeavours of musicians from past eras, both of the first and second generations, have vastly inspired the new generation of Kikuyu artistes to continue using the sound as a tool for introspection.

By Frank Njugi

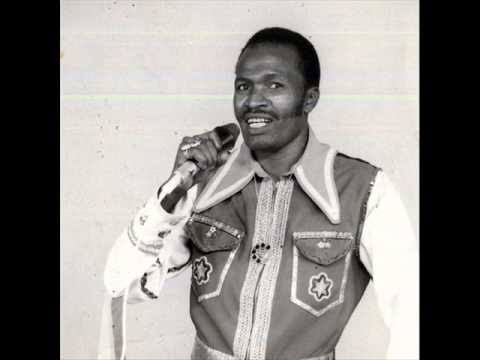

In August, twenty-six years ago, Kikuyuland (the largest ethnic group in Kenya) laid to rest, John Ndichu, one of the most prolific musicians to come from the tribe. Given the byname, “The Wonderkid of Kikuyu Benga,” Ndichu used Benga music, synonymous with a hasty rhythmic beat and a bouncy finger-picking guitar technique, to narrate his tribesmen’s triumphs, alongside their trials and tribulations. His still-famous songs such as “Thina wa Ndichu,” a nostalgic tale of the melancholy experienced with a sickly wife in the slums of Mathare, and “Mama Ciru,” which narrates how lovers can become estranged, have for years been the delight of his Kikuyu tribesmen. This is because these songs espouse unchanging daily life occurrences, even in present times.

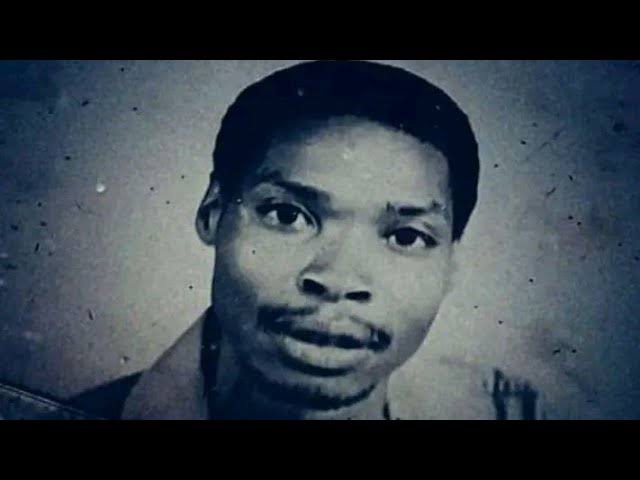

Ndichu’s musical sound and style are, however, not original to Kikuyuland. It is rather, a borrowed entity. Benga music is native to the shore-dwellers of Lake Victoria in East Africa – the Luo tribe. They brought the distinct music to other Kenyan communities, mostly through their rural-urban migration to Nairobi, shortly after independence from British colonial rule in the 1960s. Through intra-communal interactions, early Kikuyu Benga artistes borrowed the sound from their Luo counterparts. The likes of John Kamaru, Lawrence Nduru, and Francis Rugweti, in the late 60s, adopted the Luo style – characterised by a rapid plucking of single notes by guitar pickers – and fine-tuned it with a newfound dexterity, and with the invention of the electric guitar, added pizzaz to the new sound influenced by country and Western music.

They gave their new style the name, Mwomboko, which also became the general term for Kikuyu secular music. This new version of Benga music became known for its political messaging, addressing civil issues that affect their tribesmen, while also narrating other sociocultural aspects of the Kikuyu. Due to their stature as the first-ever artistes to use this borrowed version, Kamaru, Lawrence, Francis, and co became known as the first-generation Kikuyu Benga artistes.

(Read also – Storyteller and Gentleman: What Is the Measure of Mike Ejeagha’s Influence on Highlife Music in Nigeria?)

Among them, Kamaru garnered the most fame, mainly through political signalling, drawing the attention of those at the helm of political power with his music. Today, his songs such as “Muhiki Wa Mikosi,” “Kenya Ya Ngai,” and “No Ithui Twari Kuo,” are spoken of with the level of respectability that only a pioneer of a genre would attract. The Kikuyu recognise his songs as tools to not only become conscious of the tribe’s history but also to remember the country’s colonial legacy.

But while Kamaru, with his generation of artistes, is credited for pioneering the Kikuyu version of Benga music, Ndichu and his generation of Benga music singers, brought the sound more eminence. Ndichu and his cohort, who became known as the second generation of Kikuyu Benga artistes, stamped the genre and made it become the ultimate version of secular music within the Kikuyu tribe.

As such, in the 70s and 80s, inspired and mentored by the pioneering generation, the likes of Jimmy Wayuni, Kariuki Kiarutara, John De’Matthew, Joseph Wamumbe, Timona Mburu, Peter Kigia, Kimani Thomas, Simon Kihara a.k.a Musaimo, and Ndichu himself, took the genre and gave it the flair that it is still associated with, engraving it as the mirror of Kikuyu social culture.

Thika-based aspiring Benga artiste, Raphael Irungu, reveals that songs by the second generation had something that the first generation sometimes lacked – the relatability of their music. “While Kamaru and the likes introduced the genre to the tribe, it was Ndichu’s generation who largely made the genre a revelation to our people’s situations. Growing up, we would hear Kamaru’s songs and be delighted, but in retrospect, some of the things he sang about felt foreign. But Ndichu and his compatriots sang of realities similar to the conditions we grew up in. This shows how there has been a minimal change since then, and this has inspired us to continue speaking about similar stories.”

(Read also: What We Speak of When We Talk About Osita Osadebe and Highlife Music)

With the second generation, Ndichu became what Kamaru was to the first. Among his compatriots, he was the most famed. In 1978, he released the song “Cucu Wa Gakunga,” which narrates his childhood and roots. The song is also a metaphorical inspection of the social life of the Kikuyu people and is today considered one of the best Kikuyu Benga songs of all time.

Ndichu’s songs are considered allegories of both the strengths and fallibilities of the Kikuyu tribesman. Nairobi-based music teacher, Ann Wangui, speaks on the influence of Ndichu’s music, “If you are a Kikuyu who grew up around Central Kenya and its hinterlands, you grew up with parents to whom Benga was one of their core delights. They influenced us to listen to Kamaru and his folk narrations, as well as Ndichu. But Ndichu kind of appealed more. Maybe because his lyrics dived into scenarios we witnessed firsthand. He made us see music as a tool for our own stories. And that’s where we fell in love with the sound, as we saw it as the canvas upon which our essences were portrayed.”

Over the years, Kikuyu Benga music has become one of the portraits of the Kikuyu. The endeavours of musicians from past eras, both of the first and second generations, have vastly inspired the new generation of Kikuyu artistes to continue using the sound as a tool for introspection. The ones currently active in the Benga music scene, such as the likes of Samidoh, Kajimmy Manpower, and Waithaka wa Jane, have all paid homage to these artistes from the past. They do this primarily by maintaining the guitar elements in the performance of Benga music and by retaining the themes from the old ways in their song lyrics. The present generation still sings of the lives of the Kikuyu people, and although the pioneers are long gone, for the Kikuyu, their legacy is one that is fondly remembered by tribesmen.

Frank Njugi is a Kenyan writer who has written on culture for The Moveee, Afrocritik, Africa in Dialogue, The Cauldron, Salamander Ink Magazine, and elsewhere. He tweets as @franknjugi.