The chapbook contains memoirs of the melancholy of survival during the pandemic and the forlornness of the world. Written as a kaleidoscopic view of this state of ennui through the eyes of the different artists… these essays propel us to certain parts of ourselves that the journalistic cameras of the media could not take us to, especially into how individuals survived.

By Nket Godwin

Three years ago, the coronavirus pandemic (almost) turned the world into T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem, “Wasteland”, leaving nothing but debris, an existence only characteristic of World War I, and more ravaging than the 1918 Spanish Flu and 1957 Asian Flu. The root of existence was undoubtedly shaken. We groped for a handle to life and fretted about the future of humanity.

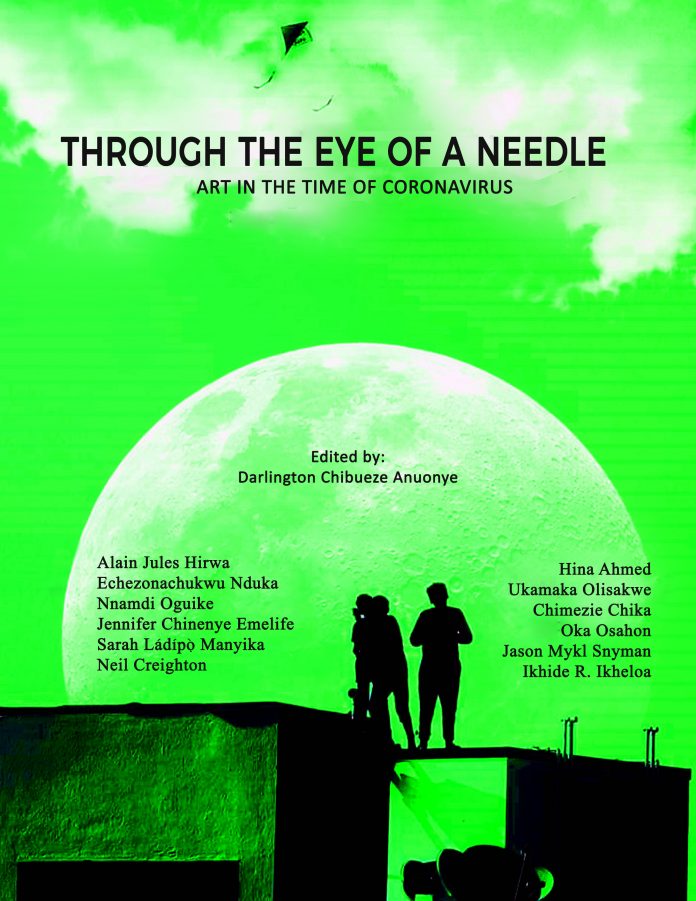

Trapped within the confines of our homes and selves, art — in all its forms — became an invaluable element of our survival. One of the testaments to that indelible period in human history is the 2020 collection of essays, Through the Eye of a Needle: Art in the Time of Coronavirus, published by Praxis Magazine, and curated and edited by Darlington Chibueze; a chapbook of twelve essays which straddle the philosophical insights and foresight of artists from Nigeria, Rwanda, US, Italy, South Africa, and Australia, on not just the pandemic but the future of humanity after the virus. Containing fifty-five pages, the essays take readers through a melancholic foray into personal, communal, national and even international trauma, economic downturn, hardship, social retardation, and apprehensive silence induced by the sudden lockdown. While the artists turn to their art, with the hope that the world could find solace, the collection behoves us, as Chibueze says in the introduction, to “pay attention” to the implicit meaning of existence lurking in the reality of the pandemic.

In these essays, the artists are “caught, but not trapped in the fearsome web of the pandemic”, as Chibueze puts it, although sombre, they philosophise survival and humanity. They listen to the world’s throbbing, sieve through the past in hindsight, collect insight from their present, and look with foresight at the world and human existence after the virus. The requisite of art here is not only to assuage our grief but to have a deeper understanding of existence and our humanity, for, as Chibueze says of the artists “they do not lament so inconsolably about their private loss; they rather transcend their misfortune in their human attempt to console the grieving world, ultimately establishing kinship with the dead and the dying, proving, especially in this time of physical lockdown, that the warmth art offers can dispel loneliness and chase away fear”.

(Read also – Chidiebube Onye Okohia’s Of Dark Tides And Darkling Times is a Philosophical Exploration of Life)

The chapbook contains memoirs of the melancholy of survival during the pandemic and the forlornness of the world. Written as a kaleidoscopic view of this state of ennui through the eyes of the different artists; both from the vantage point of their private lives (as in Echezonachukwu Nduka’s “Art as a Lifeline” and Ukamaka Olisakwe’s “Art as an Escape”) and general reflections on the virus (as in Jason Mykl Snyman’s “What Kind of Animal”, Oka Osahon’s “The World Does Not End Here”, and Chimezie Chika’s “A View of Hope”), these essays propel us to certain parts of ourselves that the journalistic cameras of the media could not take us to, especially into how individuals survived.

Also, the reality of the virus added credence to the truism that certain aspects of our existential constructs are not as important as we make them seem. For instance, in “The Art of Small Spaces”, Alain Hirwa particularly laments racial construct, especially, as demonstrated by the former US President, Donald Trump, who, suspicious of China (because the virus seemingly originated from there), declares it the “Chinese virus”, oblivious of how it perpetuates schism and widens the margin in human relationship, particular in the face of such threat as the virus. Indeed, as Hirwa reveals, “racism is an invented form of ignorance”, especially when it pits our empathy against the humanity of others.

Toeing the religious line of being, Hirwa takes us back to the sanctity of our bodies. For instance, not being able to worship in a public space called “church”, the coronavirus experience attests to the fact that there is a “smaller space” where God also exists: our bodies. Else, how could we have worshipped Him amid the socio-religious lockdown? The body reclaimed its sanctity, proving that “it is the true spiritual temple” (as 1 Corinthians, 6:19 shows), which should also be paid attention to.

Ikhide Ikheloa’s assertion, in “Art in the Age of Anxiety”, that “the artist is a human being, as the human being is an artist”, attests to the fact that every artist is first human before an artist, as this — if nothing else does — makes their stories carry certain inevitable relativity with the human condition, although theirs seem different in a particularly insightful way, in that they bring the philosophical to bear on what may pass for “an ordinarily inherent” human condition. Also significant here is that “attentive art” fosters hope and restoration, and eases emotional aches caused by the virus, and by extension, any human travail.

(Read also – Nnamdi Ehirim’s Prince Of Monkeys Captures the Trauma of a Generation)

In Echezonachukwu Nduka’s “Art as a Lifeline” and Sarah Ladipo Manyinka’s “On Being an Artist in a Time of Coronavirus”, the importance of art in a time of crisis, such as we faced during the pandemic, comes to the fore. Although these works read like a narrative in privy, induced by the virus, their essays usher us into the reality of the human condition, the place of art, and our need for it. They note that art can offer us solace when the world is caught in a menace it is never prepared to face, just like the soldier (in Nduka’s essay) longing for the sound of guitar instead of the sound of cannons. To this, Nduka agrees with Ben Okri that, “art becomes most powerful in the face of death”.

In “A Great Leveller”, Nnamdi Oguike’s inspection of humanity before the virus is gripping, as he reveals that prior to the pandemic, humanity was like a desert where we existed almost in isolation, dispersed by religion, social stratification, economic disparity, race, creed, and continental (geographical) mirage. “The world, as we have known it since we were born, has often emphasised our differences. Of course, we have differences. But, sadly, our differences have been exploited to pit us against one another,” he laments. However, the virus came and compelled us to recognise and, thus, turn to our collective humanity, in spite of our socio-cultural, religious, or racial differences. He goes further to encourage us to hold onto such leverage. For him, fighting the virus as one humanity goes to show that we are naturally intrinsic to and relative of one another than our religious, national, and racial differences make it seem, for in times like this, it is not race, religion nor nationality that would sustain us, but our collective humanity. Hence, he implores us “to think.” But are we thinking? Aren’t we bent on exterminating nations, even after all that the virus did?

The concern for the “art of attentiveness” inspires Jennifer Emelife’s rhetorical title: “What’s to Become of Us When It’s All Over?” Her essay is undertoned with the latent concern, which, preoccupied with the quest to come out of the virus, we might forget. It is a foreshadowing of what the world should look like after the virus is gone; for, as Oka Osahon says, actually, “The World Does Not End Here.” Sure, just like the 1918 and 1957 Flu, even the 2014 Ebola, this, too, must go. And, like a sea on which a boat chugged through, there would be trails in certain areas of our existence. Hence, we must pay attention and think, using such experience as the basis of our thoughts.

Nket Godwin is a poet, essayist, and book reviewer. His works have appeared on Afreecan Read, Eboquill, Inkspired, Best Poet of 2020, published by Inner Child Press, USA, Con-Scio magazine, etc. He writes from the city of Port Harcourt.