Chidiebube onye Okohia thus takes us through the anxieties of youth, the travails and dangers of living and existence on earth, and into the dreams and memories of the evening of life…

By Chimezie Chika

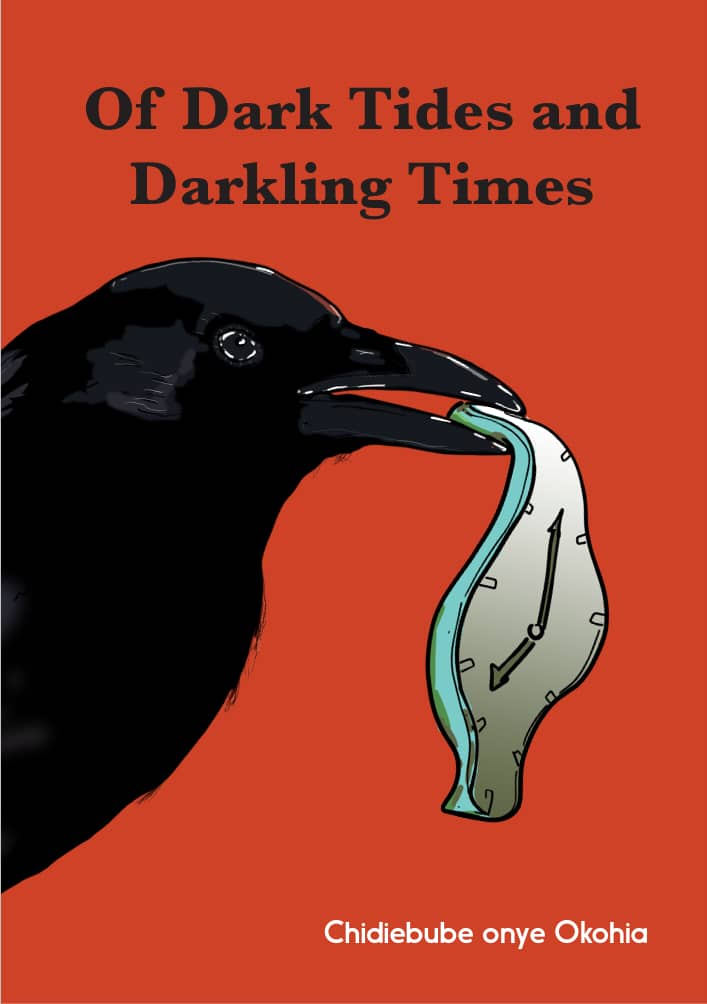

The first thing one notices a few pages into Chidiebube onye Okohia’s poetry chapbook, Of Dark Tides and Darkling Times, is the author’s laidback philosophical vision of man’s journey through life. From such varied experiences as love, religion, environment and politics. There is attention to times and its movements. The poet seems to see everything through a dark screen. There is no glorious exaltation of man’s achievements here; onye Okohia’s dark vision sweeps over everything, picking and examining our most remarkable failings in life and on earth.

The first poem in the chapbook follows this trajectory. In the first poem in the collection, “Old, Older, Olden,” the poet acknowledges the event of getting older and wiser as he relives the years he spent in the university. The phases of life passes from innocence to experience—William Blake says—and here onye Okohia takes a panoramic view of his life in the past four years. He sees his toils, his suffering, his growth, and in the end he doesn’t seem satisfied. There is a palpable anxiety for the future, for he realises that he had grown wiser and thrown away all the ideals of his early years. “This grey youth speaks of gayer years,/Four years—the friends forged, lessons learnt,/ . . . Tall tears that stole your eyes . . ./ Yet these dying minutes betray us with mild memories of regret.”

The exploration of the travails of youth continues in the poem, “Jong Bloed,” in which he images youth as a time of prolonged anguish and anxieties. “Youth is a falling rain,” we read. It “dazzles in its aery flight.” The poet sees life as the weather, whose transient seasons are only for a time. Youth, being of those seasons, is “young and fresh.” But he also acknowledges how youth is shadowed by a looming change: “Still the thunders shake and blare.” And he pleads: “Let Time pause its monstrous change.”

(Read also: Nnamdi Ehirim’s Prince of Monkeys Captures the Trauma of Generation)

Deep into this chapbook, one notices a number of things. Already, one sees a Blake-esque progression from innocence to experience, from youth, environment, and young love to eroticism, religion and politics. There is a remarkable luxuriance of words, words both archaic and current. The poet possesses an ear for rhythm and sound, in a poetic sense. In many of the poems, his style is noticeably old-fashioned—marked by the sense of rhythm that comes with attempts at metric patterning—like something straight out of the 19th century. Words such as “benumbed,” “anon,” and others words peculiarly prefixed with “a,” “be,” and other morphemes litter the collection. Exclamations are marked by the use of “Oh” or “O,” and there are unusual sentence constructions with biblical origins. This one in the poem, “As Dying Sun,” says: “When new gods to him have ruined and racked?”

The conclusion is that this is a poet firmly entrenched by 19th century poetry and even more specifically influenced by the Romantic movement of that time. The poet’s stylistic focus on these literary trends of bygone years does not detract from the fact that some of them are still very relevant today, especially in the comparison between Romanticism and the green revolution geared towards climate change. In poems such as “O Plant,” “Late Bloom,” “Our Earth,” and “Green,” it is not hard to see where the poet’s allegiances lies. In these poems, his searing concerns for the environment are self-evident. The poet is attentive to the notion that the pain of the world is that of climate change and man’s contributions. All of our contemporary anguish are tied to this disaster of existence.

Onye Okohia’s tone in the poem “Green” seems to be one of resignation. We observe that, “There are no more short shrubs and tall trees/in the straight posture, standing position;/They are all sawed, sawed; they’ve all seen the sword.” Humans destroyed nature, the poet tells us, in their craving “to be lord.” In the next instance, he vindictively calls humans “guilty-guiltless earth-killers.” There is contemporary relevance in the discussion of climate change, for it affects us all. All over Africa and the rest of the world, there are stories of flooding, rising sea levels, desert encroachments, deforestation, and wildlife poaching. Hardly a day passes that we do not read these things in news reels. Its effects are visible to us but the destructive greenhouse emissions are relentless and unending. In “O Plant” the anthropomorphic carnage on earth seems to have led the poet to remind us that the earth is there for our enjoyments, and that there will be nothing to enjoy if we destroy it. In short: we will die if the earth dies. “When I’ll be draped with death/You shall die too.”

Onye Okohia’s Of Dark Tides and Darkling Times showcases, in large part, the poet’s alliterative virtuosities. He seems to enjoy the music of alliterative lines. One nice example suffices in the oxymoronically titled poem, “Live Death”: “As years go gargling with godspeed.” Other good examples include: “for the man is full, fit, but we fight for form” (in “We Are Used to the Norm”), “You bought me flowers that are fires of your feelings” (in “Luciet”), “The sliver-silver stars are scarce now” (in “Life-Lights”). In exploring the onomatopoeic properties of alliterations and assonance, the poet seems hell-bent on a rigid adherence to the old poetic practice of sound, rhyme, and form. This is not bad in itself, but comes out as exhibiting an obvious tendency to intentional pun. In truth, it can be a little too much at times. For instance, I am not sure why the poet seems to believe that his interest is best served by overloading these lines with alliteration: “momentous moments” (in “Religio”), “love lured lust to leech me, I prayed as a prey;/All my will washed, my wish waned;/My woman dried, my worth drained” (in “Luciet”).

Some of the best poems in the collection are about religion. This may be due to the fact that the style fits the poet’s often high-flown biblical language. In “On the Progress of Faith,” the poet begins contemplatively: “A faith ago/I munched and crunched . . .” In “Fyke From Sky” one lines says of the negative part of every human, “Though my Thomas thoughts stroll like the Devil.” The poems on Lent (“Lent I” and “Lent III & IV”) reflects a mind concerned with questions of the soul. The poet dwells on the human need for the redeeming light of religion. Here we find some of his most deeply affecting lines.

(Read also: TJ Benson’s Ambitious Debut Novel, The Madhouse, Takes Nigerian Literature to New Heights)

The poems that give the collection its tempo and tenor philosophises grimly on life, and the act of living. The final lines of “Overmorrow” touches the core of this temperament: “The grating of faith against fate is my best bluff; /How failure pressures in the face of prayer.” These poems speak directly to the human condition; to failures and the pressures of living, the successes, to fate, and to memory. In the poem, “In Memory,” the poet reflects on the making of memory, “Those that I have always loved their ambience:/I still sniff the aroma of the dust of lovelies/who weaned my mind with memories.” These memories are what keep us alive, if they are good. But we are also alive because of the possibility of hope and dreams, the poet seems to imply. “We’re alive with light’s colour sparkling and brighting . . .” And in “Weed-Like,” he ruminates: “our masterpiece dreams are weeds/they feed and feast on other fields . . . As one will want to aspire/Branding his name on the world’s lips.” What makes our lives meaningful here on earth is our constant striving for the colours of life and the dreams that brighten and enrich our memories in old age. Chidiebube onye Okohia thus takes us through the anxieties of youth, the travails and dangers of living and existence on earth, and into the dreams and memories of the evening of life.

(Order Of Dark Tides and Darkling Times here.)

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Republic, The Shallow Tales Review, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Efiko Magazine, Brittle Paper, and Afrocritik. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.