What we will realise immediately is that the nature of the act of plagiarism itself is buoyed by a desire to attain preset standards of success by copying what is already successful.

By Chimezie Chika

The Scandal

On the 5th of March 2024, Nigerian poet, Pamilerin Jacob, revealed on X (formally Twitter) that his work had just been egregiously plagiarised by another Nigerian poet, Ojo Taiye. The fallout of that announcement ignited vituperations which came from anger and hurt across the Nigerian literary community. For many of the poets who expressed their shock through the succeeding days, not only was it a mortifying situation, but it also revealed the deep, convoluted, and dexterous nature of these thefts of intellectual property, entwined as they were with the normality of the everyday pursuits of the literary enterprise.

This is not to say that plagiarism is a new phenomenon in Nigeria or anywhere else for that matter; the problem with the present case, as these concerned poets acknowledge to themselves, is that it may begin to call into question (at least in part) many of the poetry being produced in Nigeria now. To even begin to understand and consider the uncertain solutions being proffered towards this problem, we must get back to Ojo Taiye.

Jacob’s rueful announcement, as dust-raising as it was, was the second time Taiye had been accused of plagiarism. Back in 2019, Taiye had been involved in his first major plagiarism scandal. After admitting that he won that year’s Jack Grapes Poetry Prize with a plagiarised poem, Culture Daily, the journal that organised the prize, announced that it was rescinding Taiye’s award with immediate effect. Of the two poems Taiye submitted, the first, “There is Nothing You Can Do to Replace My Fada”, won the prize, while the second, “My Little Cousin Came to America Armed with Just a Few Phone Numbers & Four English Words – ‘I Am a Refugee’” made the Finalists. Upon revoking Taiye’s win, Culture Daily reiterated its commitment to authenticity in a statement on its website: “Culture Weekly stands for creative voices, the uniqueness of each person’s contribution, and resolutely for the importance of acknowledging the authenticity of an artist’s work. This is especially vital for poets, whom our society gives so little in the way of accord or remuneration: poets’ work and the publication of it is, for most, the grandest compensation.” This statement is similar to the one Afrocritik made condemning plagiarism in no uncertain terms, the same stance as has been taken elsewhere in the world among serious media institutions.

The last sentence of the statement captures the reason behind the bitter sense of betrayal that poets — and indeed writers in general — feel when their work is copied or appropriated without due acknowledgement. To be acknowledged as having originated a piece of work is, for all writers, part of the contract of the literary vocation; if that work turns out to be enduring, the name of its author becomes immortal. Part of a writer’s motivation, in a vocation in which lifetime success is a gamble, is the residual knowledge that being an artist is a stab at immortality. To be a poet then is to be aware of — and to respond to — this fact in an even more personal way, for poetry is the least financially rewarding of all the literary genres. Many poets write because they want to express themselves and because they can find no other natural route to enact, through literature, a human engagement with life as it is lived and felt.

I do not know for certain the motivations behind Taiye’s poetry. But there are few things we know. The first is that he was born in 1992, according to a Wikipedia entry in Hausa, though even this is not certain. Elsewhere, his original name is identified as Peter Ogun, which arguably makes “Ojo Taiye” a pseudonym. We also know that his poetry has won several awards and has been published widely in journals and magazines across four continents, including Grain, Lambda Literary, Strange Horizons, Banshee, Rattle, Frontier Poetry, Notre Dame Review and many other places. The sheer amount of Taiye’s publication history is prodigious. Everything in his resume points to a poet who has enjoyed relative success by any standards. Taiye remains one of Nigeria’s most successful, prolific, and frequently published poets. There is a view among some of the people I spoke to that this is a poet talented enough to fare well without sneaking other people’s lines into the dense thicket of his poems. Jacob, for instance, acknowledges that he had enjoyed Taiye’s poem in the past. “At least once, I have found solace in his poems. For me that was enough to consider him worthy of attention”, he said, “He ‘wrote’ a poem years ago called “Fuck Suicide” that has stayed with me over the years. To think that he may have stolen the lines is disappointing. It feels like a deconstruction of faith and it is unfair to the reader. He spat in the faces of all who thought him redeemable in 2020.” Talking to people, I realised that the scandal resulting from Taiye’s questionable poetry awakened a specific kind of commentary, especially with regard to the larger literary community in Nigeria. But we will come to this.

After his misadventure with Culture Daily’s literary prize, Taiye’s poems shifted towards ecological themes within a couple of years (One realises, after a time, that this poet is a master of the volte-face, rebranding and making turnarounds when it suits him best). Within the same period, he largely stopped publishing in America, which is the geographical abode of many of the magazines and institutions supporting and publishing African poetry today, and pivoted to European and other non-American journals where he began to submit his new-fangled climate-conscious poetry. He changed his bio and began to identify as a ‘climate activist’ (Before then, he had used variations of the phrase ‘a young Nigerian who uses poetry as a tool to hide his frustration.’ After the scandal in March this year, he adjusted his bio yet again — another volte-face — this time claiming ‘intertextuality’ for his poetry). But the interesting question here is why he was compelled to leave the American poetry space. A few people have conjectured that it could have been because he felt that his name had been sullied in the Americas, which may not be entirely plausible. Whatever his motivation for the change in location, it reveals a certain intransigence of spirit — it seems to be the typical reaction of a character who is not ready to face his own failings squarely with dignity, but one who, instead of doing that, goes to a new hideout to continue luxuriating in his shortcomings.

Given Nigeria’s political and economic quandary and its long tussle with its oil wealth and the attendant ecological damage that accrues from it, Nigerian poetry is not new to the subject of ecology and environmental despoliation. Many of the poets who have concerned themselves with that subject are from Nigeria’s oil-rich Niger Delta region and include such notable names as Gabriel Okara, J.P Clark, Tanure Ojaide and others who felt real concerns for the land of their natal origins. As a poet, Nigerian, and human being, Taiye’s climate activism appears to be honest. Watching his videos, his personage seems to exude genuine interest, calmness, and even sensitivity. His social media accounts are filled with flyers and statements linked to climate activism. He has also attended a number of ecology-themed conferences where he has read his poems. There is nothing in his demeanour that projects a dishonest, much less a stubborn, personality. But these are only observations that lack the privilege of proximity. What is not clear in his trail of success is whether all his poems are plagiarised in some way. Is there some redemption of originality for him? Even if there is, his poetic practice, however genuine much of it might be, has been tainted irreparably by this second and most recent plagiarism scandal.

The Nature of Plagiarism

Jacob had posted a screenshot of the two poems when he made that uproarious revelation in March. The two poems, his and Taiye’s, show striking similarities. Upon discovering that he had been plagiarised, Jacob experienced a rush of emotions. “I felt stunned, violated, and a little worried I was overreacting. This was someone who had been given a second chance, so I thought, surely, he wouldn’t do that. I went back to check the poem . . . I didn’t even see the other parts of the poem he stole, until someone else pointed it out, because I’d closed his poems and made that tweet”, he said. Baffled by Taiye’s behaviour and his insistent repetition of wrong-doing, Jacob tries to make sense of it: “In Christian theology, the only unforgivable sin is the constant rejection of grace throughout one’s lifetime. This is the Ojo Taiye story. He enjoyed a superabundance of grace from the Nigerian lit community, but being shrewd, utilised that very grace for self-gain at the expense of his peers. There are some things to note: amid the debacle, he went quiet, wishing amnesia upon the poetry community. Weeks later, when mags began to pull down his work, he put out an ‘apology’ demanding to be left alone. He only regrets being caught, not the plagiarism itself. Nobody is perfect, of course, but Ojo Taiye seems determined to be imperfect.”

Clearly, poets like Taiye evince bad portents for Nigerian poetry, if such actions are allowed to go without remark or action. What would unscrupulous people do when they find out that one could achieve some success in poetry by simply faking and winging it, as Taiye seems to have done? What would then happen if a generation of poetry coming out of the country lacks originality in the creative sense? If I were to guess, it would be more than disastrous. But, as any careful person would observe, the question of originality is not as straightforward as it may seem, and this is where, singularly, a lot of confusion about plagiarism emanates from.

In the academic sphere, where research proceeds on the assumption of a knowledge “gap”, and therefore assumes uniqueness, plagiarism is a most sensitive issue. This is why academia exhibits a fastidious tenacity to source citations, in which painstaking rigour is the iron rule for scholars. This delicate approach is an attempt, of course, to avoid what might easily become an appropriation of another scholar’s research.

But the boundaries of what to cite and what is essentially one’s own intellectual deductions can be blurry to the uninformed. No such excuses, however, can be made for scholars. In fact, the approach of the academic community to intellectual theft is one of uncompromising severity. We saw an example of this play out earlier this year when Harvard president, Claudine Gay was forced to resign over accusations of plagiarism after just six months at the helm. The scandal spurred opinions on the perceived complexities of Black representation, the decline of academia and, as one would expect, even unsubstantiated claims of favouritism. But this is no isolated event: institutions like Harvard and others have had similar scandals among their scholars. The consequence is usually in the form of the discrediting of the perpetrator’s reputation. There is clearly nothing more damaging to a scholar’s career trajectory.

Time-tested methods of acknowledgement in the objective world of academia may seem inimical to the emotional plains of poetry. Thus one may wonder when and how poetry can employ the technique of intertextuality without teetering into intellectual theft. Considering that, it follows logically that one must then find out, in the simplest terms, what plagiarism is. Again, we can do no wrong in trying to discern where plagiarism begins and ends. The University of Oxford gives a simple answer to that question: “Presenting work or ideas from another source as your own, with or without the consent of the original author, by incorporating it into your work without full acknowledgement.” Thus, it can be established that plagiarism is claiming credit for the work of another. All plagiarism cases have this in common. This means that a writer’s first approach to avoiding plagiarism is sincerity: sincerity of mind, of tone, of purpose.

But even with the exactitude such as we have established above, we see that there remains something of a blurry line around plagiarism, intertextuality, and literary appropriation in contemporary discourse. Some people seem to have no clue whatsoever about which is which. In my conversations with young writers, I witnessed palpable confusion as to where plagiarism ends and literary borrowing or intertextuality begins. Hence, the ludicrousness of claiming plagiarism in what has become known as “After-Poems”, that is, poems that continue the conversation of a previous poem written by another poet; where several poems can be in conversation without imitating one another — though even those are still susceptible to plagiarism, as we can see from the case of Rachel McKibbens. Such ignorant complications are precisely the reason why definite explications of contentious issues such as plagiarism are needed. In the case of the modernist Nigerian poet, Christopher Okigbo, accusations of plagiarism in his poetry are self-evident. But, in other cases, postmodern structuring, used by experimental poets to extend or deconstruct narratives, shadows such clear-eyed views of what plagiarism is. We can at least note and operate by a few unimpeachable literary touchstones involving the notion of mastery, intent, technique, and annotation.

What we will realise immediately is that the nature of the act of plagiarism itself is buoyed by a desire to attain preset standards of success by copying what is already successful. In other words, “hacking the system”. It is devoid of moral obligation, which is the prevailing impulse from which a writer sallies into the mastery of his art. Moral obligation, the choice of it at least, is what informs intent, which in turn informs technique. Intertextual poetry, for instance, is the product of a mastery of technique and intent, even though the boundaries between such a technique and plagiarism are very porous indeed; its application then demands extreme care. In this context, is there a scenario in which a literary collagist such as Zambian poet, Cheswayo Mphanza, could be tagged a plagiarist? Should his highly stylised poetry be juxtaposed with Taiye Ojo’s on the basis of their both being instances, albeit different, of ‘literary appropriation.’ If we analyse both poets’ works, and thus their creative processes, what would that reveal to us?

The application of the literary collage technique and intertextuality in Mphanza’s poetry is, perforce, a product of an artistic philosophy which undertows a manner of thinking — a style, so to speak, of reasoning. While noting the delicacy of the choice of intertextuality in Mphanza’s The Rhinehart Frames, Ernest Ogunyemi, in a review in Open Country Magazine, remarks that the technique allows the poet to create a dialogue between “literary criticism, cultural commentary, art criticism, a scholarly text” and “a conversation with the writers and artists and historical figures” that influenced him.

When Mphanza incorporates a line from elsewhere, he is not using it directly as his own but in juxtaposition of thought and image. The extracted lines offer a continuum of old, established (even frozen) thoughts into the poet’s own current, urgent, and flowing images. And he carefully attributes his sources:

“On a street discreet as our intent, searching for Mr. Badii’s perfect burial, the lakefront’s scent curls around us, retreating me to sore summers.”

—from the prose poem “Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami, 1997).”

Writing on the poet’s mastery of sampling in the excerpt above, Ogunyemi notes, “Mphanza does it so well that while reading these poems, particularly the centos, it is clear that what is before our eyes is not an amalgamation of lines clipped from here and there but a culmination that is totally his. He makes better what he takes.”

Plagiarism is feckless imitation, but what we glean in the works of Mphanza and prose writers such as Dos Passos are random scraps of human thinking purposefully reprogrammed to represent the writer’s own interpretation of human experience. The pathos therein emanates from the careful placement, in opposition and apposition, of arbitrary thoughts across the extant realm of written knowledge. It is deliberate, it is bound by philosophy, it reveals something new, and above all, it is honest about what it is. All of which plagiarism is not.

As much as we may shy away from its discourse, the polyphonic nature of Internet culture and the mainstreaming of AI technology has also advanced complexity in creative ownership, so that any singular style or manner of doing things that achieves success quickly results in its widespread duplication. Recently, we saw controversy in the use of certain words which, having been coded into the diction of AI language applications, have begun to be seen as humans copying computers. Thus, simultaneously, we are assaulted daily with the complexes of a democratised culture of appropriation. The influences that accrue from this prevailing culture must have affected the nature of our literature in the age of social media.

The Limits of Plagiarism

So here is Taiye, the embattled poet. I conjecture that he does not think about plagiarism when he initially sits down to write; perhaps when he sits at his desk, what first comes to his mind is how to be successful, and how to move ahead in the literary world. How far can one go to get that? So, again, here is Taiye, or a certain unknown young poet somewhere in Nigeria, riveted to the disingenuous idea of appropriating poems he read and found remarkable; creation means nothing to him at that point other than a carrying of the unique creations of other poets into his own larger ideas. It beats understanding in certain ways and yet it makes sense that such an act could come from a culture that has turned itself into a highly competitive, wolfish world.

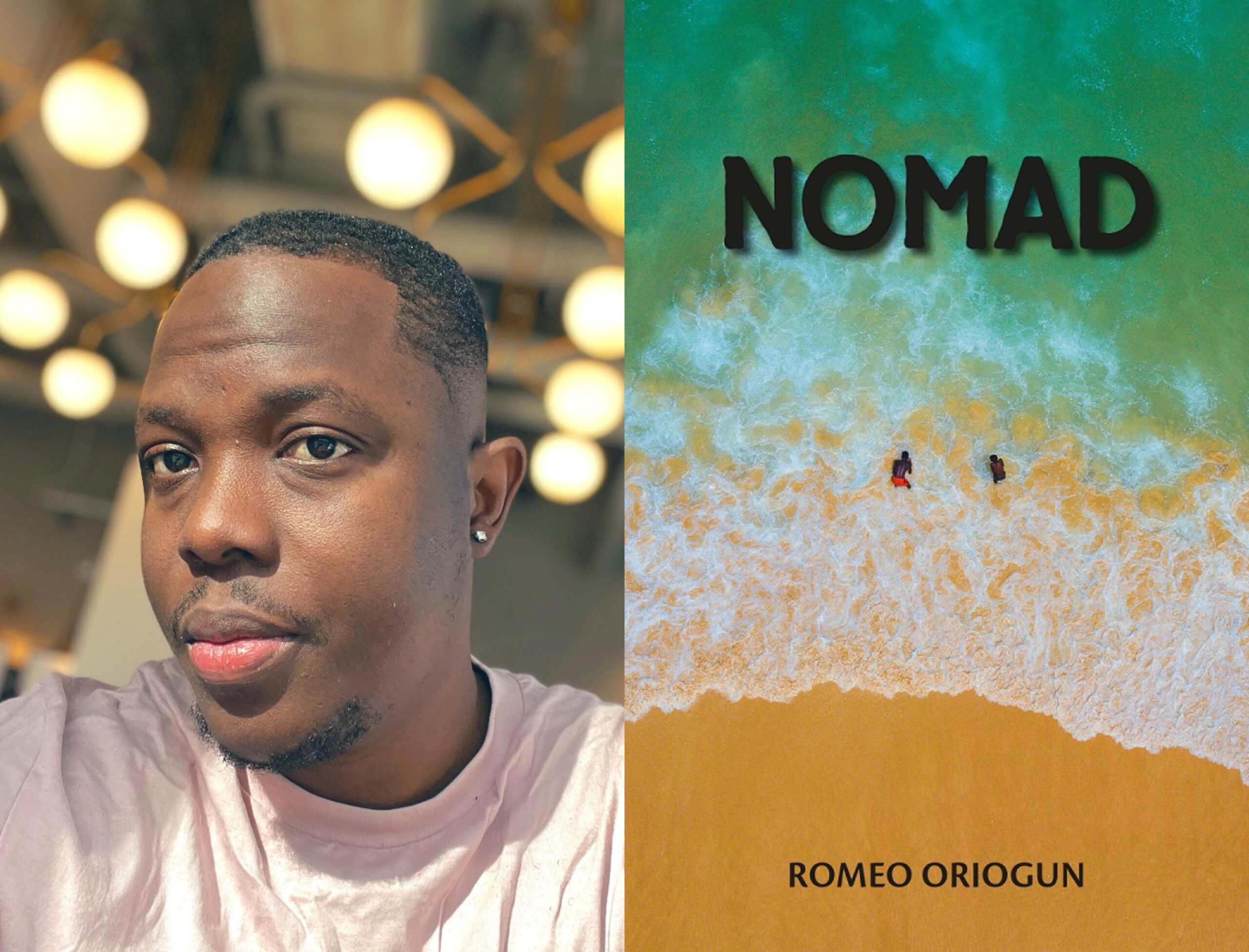

Any poet with Taiye’s rising pedigree in any literary scene tends to have an immediate influence on the aspirations of much younger poets. In a literary culture that obsessively accentuates success in poetry, perhaps because the incidence of success in the genre is so rare (though putting finances first in the pursuit of the arts seems rather misplaced), we have seen adoration — and imitation — of our most accomplished poets of the last decade. Among them, Romeo Oriogun is arguably the most copied, especially after he won the Brunel Poetry Prize in 2017. But there are other stalwarts such as Adedayo Agarau, Gbenga Adeshina, Gbenga Adeoba, Nome Patrick, and others, whose styles and verbatim sentences are leaving a slew of private production lines in mass-produced duplicates for the American literary magazine market. One only needs to take on the position of ‘Reader’ in these magazines to get an inkling of the scale of copycatting going on. When poet and editor Jide Badmus announced on the 6th of April that a poem written by a mentee of his and published in a newly released anthology he co-edited had plagiarised Dami Ajayi’s “How to Grieve in Time” (the young poet had informed the editor himself), it threw the literary community into a fervid whirl and escalated conversations on plagiarism which had started a month earlier (attended by paranoia and, understandably, some sleuthing), resulting in more evidence emerging that Taiye’s plagiarism was even more pervasive that originally thought. There were strong-worded condemnations and calls for the literary community to take a stricter stance on the matter. If one takes a more circumspective posture, one must admit that the copying of the phrases and morphologies of accomplished poets can be either innocuous, as is the case of Jide Badmus’ protégé, or frenzied adumbrations of an untoward desire for success by a group of people who have identified poetry as a pliable financial racket.

Perhaps no literary genre coming out of Nigeria has demonstrated quite openly this dubious motivation, aided by the endless solipsism of social media. One sees the veritable pressure in the pattern of behaviour exhibited by young poets: there is, in short, a routine scramble to get published as much as possible and gloat over that idea of success to prove individual relevance. The resultant blur of narcissistic posts and updates that is Nigerian literary social media never ceases to baffle me; amidst the hysteria around this lurid glamorisation of achievements, I cannot think of a more emphatic inhibition to creativity. Three months ago, a friend complained to me that a writers’ group she joined on WhatsApp had deviated from its original purpose of sharing literary opportunities for mutual benefit. “I am beginning to feel uneasy there”, she said, “because all they seem to talk about now are how they are important and how they have been published in a lot of places and won many prizes.”

Any artist who has advanced in his perception of the interplay between art and life realises that creation is a thoroughly moral act. To choose to create — to make out of an idea something new and tangible — is to enact morality, for to be moral is to be faithful to one’s own innermost creative instinct, to understand as it were the need to contribute in the most honest way possible to the body of knowledge in the world. To be moral is to treat human experience with dignity, to approach it from one’s own perspective or understanding of it, and to adhere to the aspiration to be a good writer, artist, and human being. Plagiarists, by their immoral actions, necessarily go against these tenets. A writer who chooses the route of arched infelicity to the creative process sets himself up for self-doubt and a misalignment between himself, his creation, and the world — that is, his readers — to whom much of his artistic allegiance lies.

For new poets who plunge into plagiarism out of ignorance — especially because they do not know enough to know what plagiarism is — the situation is simple enough: they are on a learning curve and, if they apply themselves enough, they will gradually grow into their own creativity. Almost every writer began by imitating the great works they have read. Now, it is not clear how far talent goes, but every sentient human skill is polished through imitation, repetition, and conscious practice. If copying is a form of private practice in the quest for mastery, then we can agree that it is allowed so long as the poet does not claim ownership of lines he did not create, or go as far as trying to get them published. This is where we can find the limits. Beyond is the shady world of theft.

Where Do We Find Remedies?

Despite his infamy, can a poet like Taiye be offered expiation? Can there be redemption for perpetrators of plagiarism? If we are to judge by majority opinion, then it will be unanimous condemnation for Taiye and his ilk. In an X Space meeting tagged “Cryptomnesia and Plagiarism in the Literary Community”, hosted by Michael Okafor to discuss the issue soon after Badmus’ plagiarism notice, many poets and writers offered opinions that ranged from quite militant calls for the cancellation of offenders to that of Oriogun who feels that the poetry community should extend “grace”, as he put it, to young poets who have done the act. In his opinion, cancellation could result in the destruction of fledgling careers and cause irreparable trauma. For him, it is very likely that many of them do not know what they are doing and only a gentle approach and nurturing could address the issue satisfactorily for all parties involved “It will save their future”, he said.

In a private message to me, typically insightful and circumspect, Jacob agrees with Oriogun: “For a relatively new or ‘young’ poet, I usually just send a mail with a stern warning about what happened to Ailey O’Toole when she did it. The remedy for plagiarism is contentment. When I spent months in the psychiatric ward writing poems, adoring tons of poets, not once did it cross my mind to ‘steal’ their words or glittering expressions. And I was a young poet. In the case of a seasoned poet like Ojo Taiye, he exemplifies what Catholic monk and poet Thomas Merton noted: ‘Hurry ruins saints as well as artists.’ There will be among us those who resist patience and the ordinary life stuffed full of unbridled ambition that reduces the work to the coolest places to get published.”

At the same time, Jacob feels that harsher penalties are justified in such cases. “Due to the nature of the offence, a plagiarist invokes upon the self a variant of the Roman damnatio memoriae. The plagiarist has condemned the public for putting its trust in his creative labour by theft of the imagination. This is why the person whose work is stolen isn’t the only person who feels hurt by the offence. Literature is shared imagination. It is only normal to have the community of poets to, in turn, condemn the plagiarist to a fate of erasure. Plagiarism, really, is self-destruction.”

In Badmus’ opinion, plagiarism has a euphemistic effect on the surface in that people outside the literary sphere may even go as far as thinking that responses to it are overwrought. But he believes that the remedy is not de-platforming the erring poet. “There should be room for repair, too”, he observes, “but this also depends on the offender’s disposition.” He acknowledges that finding a solution may need research, knowing that these things happen from time to time. “It is good we are having these conversations”, he says. “I think the talk around this and taking down some of his (Taiye’s) publications here and there will serve as a deterrent to younger ones.”

Perhaps Taiye’s redemption is compounded by his silent refusal to make an apology (When he did offer one in a statement he put out a few days after the second scandal, many found problems with his choice of words and declared the apology to be insincere. But by then multiple platforms had begun to pull down Taiye’s published works after a sustained calling out on social media as a “serial plagiarist” by persons who were infuriated by what they saw as his arrogance). I am ever more interested in the remedies that could be offered in cases of plagiarism. How can it be ameliorated? How should the perpetrators be treated? In the ascetic world of academia, as can be seen from precedents, the results are usually instant dismissal. But in the literary sphere, the solutions are not singularly certain. Are all the solutions being offered sufficiently operable in the context of our national literature? Will they emphatically end any vestiges of plagiarism?

In hindsight, Jacob’s view puts everything in perspective (including my own purposes and concerns here) when he observes that the only reason why the case even achieved this level of notoriety has mainly to do with Taiye’s obstinacy. “I suppose we have his ego to thank for making his case a lesson for others to learn from”, he said. “While we elevate the deeds of our best, we must also document those who thought they could cheat the collective imagination. History is all beauty and gore. If in three years, no one knows about Ojo Taiye’s antics in 2024, we would have failed them.”

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Republic, The Shallow Tales Review, Terrain.org, Iskanchi Mag, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Afrocritik. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.

Cover Photo by Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash.