The movement towards a fusion of artistic expressions from around the world is perhaps a recognition of a more universal world, where even items in remote locations are only a click away…

By Chimezie Chika

Tribes, Totems and Culture

The period was the 1800s. The place was the flat green plains of the Serengeti — a natural stretch of green lawn where some of the greatest animal migrations take place every year — in East Africa. The people were the Masai, and the first English colonists had just come across them in their natural habitat. At the very least, the adventurous Englishmen considered them a strange and fascinating people (“Even so the manly virtues, fine carriage, and often handsome features of the Masai arouse a certainty sympathy,” wrote Sir Charles Eliot), for here was a tribe of tall, black, nomadic people of Nilotic origin, distinguished by their cattle, their red clothes, and their abundant bead jewellery.

(Read also: Lafalaise Dion is “Cowrying” Through Fashion and Spirituality)

Like the animals of the East African plains, the Masai migrate, too, moving with the changing seasons. They follow the clouds, schlepping their cattle along the Great Rift Valley looking for water and pasture. In the highlands there was fog and cold; the mornings were always white and implacable. But in those highlands, the Masai are at home with the world. There are very few immaculately preserved cultures in Africa like the Masai. The men and women, often clad in shuka and kanga blankets of different colours — mostly red — are recognisable anywhere with their close-shaved heads and the enormous amounts of ornaments they carry on their body.

Intricate jewelry is a feature of Masai culture, evidence of accomplished craftsmanship and entrenched notions of beauty. Typical Masai fashion is often assessoried with heavy jewelries: necklaces, anklets and bangles; they usually also indicate wealth and social standing, totem or clan. In most instances, the earlobes are pierced in many places and beaded ornaments strung — sometimes rather precariously — on them. Some of these piercings can be very large, with flesh hanging thinly beneath.

The red colour which is found in almost all Masai apparels is supposed to be a representation of the Masai supreme deity, Nkai, who has a dual nature, represented by two colours: Nkai Narok (Black God) and Nkai Na-nyokie (Red God). Nkai Narok is said to be benevolent, while Nkai Na-nyokie is vengeful. The Masai are a people conscious of how close blood is to all human endeavours and how everything works in duality. The major totems of the Masai tribe are represented as Red Cow and Black Cow. The corresponding presence of the colour is evident in circumcision rites, when the new initiates go about clad in black for weeks. Each colour, with its distinct tribal symbols, is represented in the ethnic jewelry. The jewelry are thus the people’s expression of their heritage. In the modern times, these ornaments are relentlessly sold to tourists. It tells a different story of the modern economy of the Masai.

The Dinka people of South Sudan are of similar Nilotic origin to the Masai, their single most visible feature being their gigantic heights. The Dinka have been called the tallest people in the world. Their culture projects a multi-faceted use of jewelry. The use of jewelry among the Dinka is a manifest striving for a kind of showy beauty in the brass and bead ornaments. The complex beadwork of the Dinka is not limited to necklaces, bracelets and anklets but includes trinkets, corsets, headgear, and garments of various shapes and sizes. The bead ornaments are not used to enhance the beauty of the human body, but they are expressions of beauty themselves and, in the culture, they embody a tribal worldview of beauty and maturity. The colour divisions of the Dinka male corset represent a man’s totem, age group, clan or marital status.

Among the Zulu and the Xhosa of Southern Africa, jewelry is a colourful, flamboyant affair. These are cultures that are blatant with their expression of beauty. The Zulus decorate everything around them — from houses to humans — with bead ornaments. Their bead jewelry has elaborate colour motifs and geometric patterns. In many instances, the Zulu jewelry is highly symbolic. They are worn by wealthy individuals and are used as amulets and protective garments in war. During courting among young people, a maiden presents her betrothed with a beaded necklace known as “ibheqe” and keeps a similar one for herself. The ibheqe is then used to pass messages between the lovers, with the messages coyly embedded in the coloured patterns. It is a complex bead language in which pattern, colour hue, and colour position, communicate meanings. For example, red (depending on the hue) can mean intense longing or anger. Blue means something along the lines of: “I am unhappy. You have abandoned me. When will you come back?” Among the Zulu, the ibheqe is not the jewellery that shows formal engagement. The ornament that bears that burden is the “ucu.”

Xhosa ornaments are beads made from glass, wood, metal, bones, sea shells, precious stones, and other similar objects which are then strung together on a tread. Although it often represents similar symbols as the Zulu bead jewelry, Xhosa beadwork seems more expressive with tangible images such as trees and geometric lines patterned into them. The beads are also shaped into skirts that mirror tribal notions of virginity and fertility.

One of the most flamboyant ethnic jewelry can be found among the Ashanti of Ghana, a culture known for their gold. Rich gold ornaments and jewelry adorn the body and garments of the wealthy during public events. Gold signifies everything that the Ashanti hold dear: their matrilineal heritage, royalty, authority, and wealth. Every article of significance is made of gold; from the golden stool of kingship to betrothal ring (petia).

Many tribes all over Africa regard jewelry as not just casual extensions of beauty, but tend to express cultural beliefs and practise with these ornaments. There are cases in which these practices may be casual, but there are others where they begin to exhibit extremities of belief systems, and somewhat unusual beauty standards.

(Read also: Subjects of Desire Review: Are We Ever Going to Get Over the Idea of Cultural Appropriation?)

A Strange and Unbearable Beauty

Indian scholar, Chinmayee Satpathy, writes that the human craving for ornamentation is due to a number of reasons, ranging from personal adornment, ethnic identity, gift exchange, status symbol, marriage symbol, body modifiers, to self-defence and symbols of mourning. He concludes that jewelry is the “most effective medium of cultural communication of human civilization,” in an increasingly globalised world which is often prey to “the potential loss of intangible cultural heritage.”

Throughout history, the craving to show beauty or make some sort of social statement with jewelry has persisted; parties and balls are filled with such visible displays. The wearing of jewelry dates back to the oldest known human settlements. The oldest humans used eagle talons and animal bones for jewelry. Kings used (and still use) jewellery to show authority; family heads wear their own special jewellery; social occasions are marked by peculiar jewelry of different shapes and colours. Ancient Egyptians were elaborate in their adornments. The rituals of burial and the afterlife are magnified by the placement of gold ornaments and jewelries — made from gold, silver, beads, precious stones and metals — in the tomb of the deceased.

This curious use of ornaments gets even stranger when different religions and spiritualities are considered. Religious ornaments are essentially utilitarian as articles of spiritual significance. African tribes from the Tswana, the Zulu, the Xhosa, to the Igbo, the Yoruba, the Mossi, and many others, have a deeply spiritual regard for certain ornamentations, whose use takes on a sacred, somewhat beatific character. These jewelries — they often come in the form of charmed amulets, anklets, and waist beads — are made from cowries, and the shells and bones of rare animals and are supposed to protect the wearers from certain evils. In any case, one cannot deny that even with such uses, these spiritual adornments are supposed to also blend in with the body, or enhance the appearance of the wearer in an unobtrusive way.

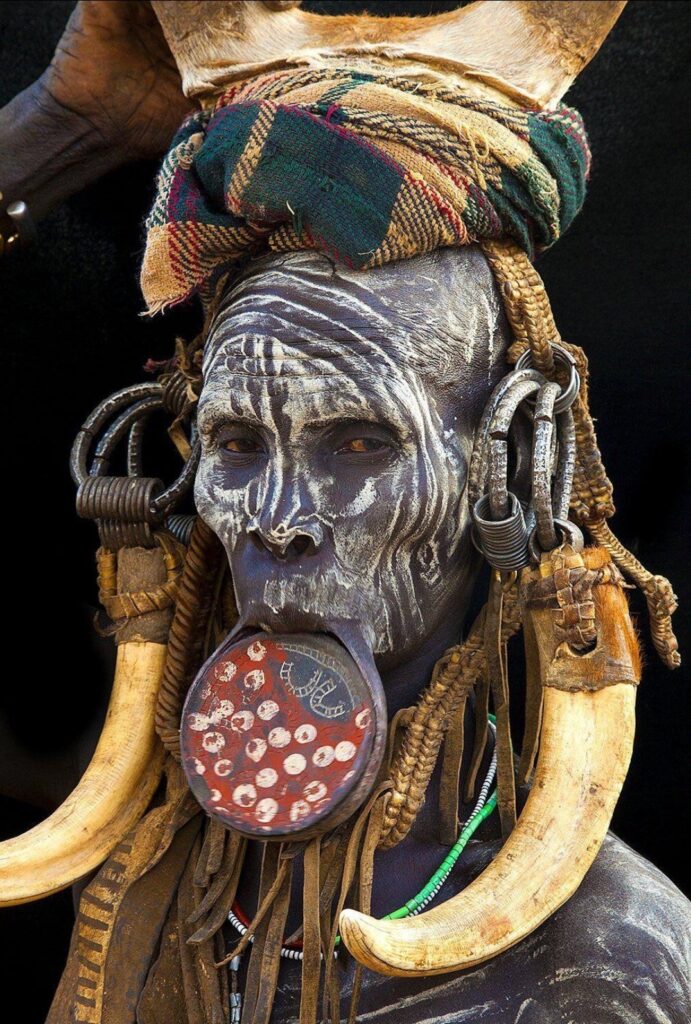

Whether religious, cultural, economic, or social, there is no one definition of what beauty represents. Beauty is what a group of people say it is. What is considered abominable and repulsing in one culture is seen as the ultimate evidence of beauty in another. There is the curious case of the Mursi people of Southern Ethiopia, who are arguably one of the most isolated tribes in the world. The interesting beauty routine of the Mursi is the insertion of wooden plates in the lower lips of young women. The plate is usually inserted just after puberty, at 15 or 16, usually by the girl’s mother who would first cut the lips and remove some of the lower teeth before inserting the plates. It is said that the larger the plate, the more beautiful the girl is considered. The Mursi also mutilate their ears with heavy iron hoops. It is not clear whether there are other meanings attached to the ornamentation of the Mursi, but their curious view of beauty certainly raises eyebrows; to the non-Mursi person, it is a strange and unbearable beauty.

(Read also: Tribal Marks: Cultural Heritage or Plain Barbarism?)

Modern African Jewelry: Is There an Agenda?

Modern jewelry wearers are simpler. Globalisation also seems to have standardised designs and practices, although of course there are still interesting people with multiple piercings all over their body. For the most part we know the uses of most of our jewelry. The wedding band for example, in all its simplicity, represents the eternal bond of matrimony between two people. Ear rings, necklaces, brooches, bracelets, anklets are all supposed to enhance our appearance.

Previous periods of modern history exact a more puritan use of jewelry — thin necklaces and finger rings and earrings — but in a more liberal world, there seems to be movements towards recalling some of the baroque ornamentations of the past. Movies and social media have made more people aware — and certainly appreciative — of jewelry of other cultures. Thus we have now begun to see an increase in the wearing of nose rings and waist rings, where there was little previously. The blatant expression of this globalised sense of beauty through jewelry seems to show a willingness among modern men and women to embrace a mix of different cultures, ideas and expressions.

The movement towards a fusion of artistic expressions from around the world is perhaps a recognition of a more universal world, where even items in remote locations are only a click away. African jewelry designers such as the South African company, Lashongwe, have found new ways to merge elements of Zulu ethnic jewelry and western designs. Other designers across the world have incorporated motifs from African cultures; European designers are constantly accused of stealing African traditional cloth patterns — Beyonce suffers the same relentless accusations for her Africa-themed outfits and jewelry, the cowrie shell dress in her “Spirit” music video being an example — which has been criticised in certain quarters as an instance of cultural appropriation. In the context of the modern world, arguments around “cultural appropriation” are no longer compelling and run the risk of being nothing more than obtuse gatekeeping.

Whether Western or African, modern designers are artists with the freedom to explore their artistic sensibilities in minimalist or maximalist creations. In our thoroughly globalised world (the age of television, mobile phone, and social media), there is a hankering towards artistic expressions that fuse versions of cultural practices around the world. This is the basis of ideologies like altermodernism; jewellery and ornaments are also part of this new global ideology.

But is there a visible agenda behind these? If there is anything to say for it, it is that, apart from specific tribal symbols, the basic reason people wear jewelry has not changed over the years. It is still, at its most basic point, a question of beauty, status symbol, and wealth. What is evident in the modern world is that more people have the purchasing power to buy more expensive jewelry, and more people have become more aware of how they are used in other places.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.

I’m very pleased to learn such brilliant piece of article. I appreciate your hard work. Thank you for sharing. I will also share some useful information.

I appreciate your hard work. Thank you for sharing. I will also share some useful information.

Many tribes all over Africa regard jewelleries as not just casual extensions of beauty. Each African piece of jewelry contains its symbolism, reflecting the way of life, the unique culture, and the history of the tribes.