Africa must begin to choose its own heroes, heroes who are not determined by the haughty opinions of outsiders, but by a country’s particular understanding of its own history…

By Chimezie Chika

The political failures of Africa are well-documented across history and media. The story of neglect trails its political landscape, and many of its contemporary cultural endeavours are sustained by largely private enterprise, with no help coming from the government. Africa’s heroes and relevant historical structures are either in the doldrums of oblivion or are not being immortalised enough by the machinery of state. Some people may ask if this is a valid concern in the light of more pressing problems in Africa. However, it is clear that, in postcolonial Africa, the bulk of attention have been paid to less pertinent issues. In the march towards finding lasting solutions to the continent’s many problems, one of the questions that must be asked is why Africa is not commemorating its heroes and its defining historical events enough. The public image of nations is sustained by the great individuals that have shaped their history and nationhood, and the strategic historical events that became the touchstone in the realisation of their national identity. The cultural prestige of nations—indeed what enhances their standing in the league of other nations—rests on how they project the work of individuals and events that shaped the histories of their countries.

(Read also: The Single Narrative about Africa is Exhausting)

Why is it so important to create such memorial fanfare around historical figures and events that have shaped a country? Is it enough to acknowledge their contributions once and for all and face other issues? The answer to these questions is that the cultural and social values of a country are manifested in its iconography. Heroes, freedom fighters, and even war help to form a people’s sense of collective identity. The citizens and the rest of the world get to know about a country’s journey through its heroes, historic events and important individuals. The mention of the name of a country causes the recalling of the image of its perennial hero or heroes, as in South Africa and Nelson Mandela. Commemorating a country’s important icons is an important source of documentation for posterity, so that young people may look at how far their country has come and be able to build from an established precedent while paying homage to their illustrious forebears.

History and the Importance of Monuments

Countries in Asia, Europe and America have filled our consciousness today with images that project their crucial place in the world because of the manner in which they have been able to convince us of the insuperability of their own greats. A perfect example is the world’s tallest statue, the 597 feet tall Statue of Unity, its cultural significance to India is in how it commemorates Indian independence icon, Vallabhbhai Patel, who unified India. In any discourse of Western countries, their heroes and defining events, we are always inundated with a vast plenitude of information in physical structures and artefacts, in buildings, in books, and in the media. In these actions, there is a concerted effort among these countries to create a distinct picture of their own greatness in the minds of the rest of the world. And what better way to do it than through the loud commemoration of individuals and events that has contributed to their existence.

Much of what comes to mind at the mention of France comes from our awareness of the French Revolution of 1789, and the wars of Napoleon Bonaparte, or even the Norman invasion of Britain. These events, which give French people a sense of identity, are commemorated in the famous Bayeux Tapestry, which has survived centuries, and in structures such as Place de Bastille, La Conciergerie, Palais Royal, Pavilion de Flore, Place de la Concorde, and others. A typical tour of America takes a stranger down the same lane. Wherever you are in the world, you get a picture of America’s sense of its own past and current standing in the world from how it continues to build structures and sculptures marking its heroes and defining historical moments. From the sculptures of Abraham Lincoln, the White House, the thousand headstones of Gettysburg, the Statue of Liberty, amongst others, America invades our consciousness from every angle and speaks to us of its own nationhood and greatness. Abraham Lincoln famously has more than 15,000 books written on him. There are many national holidays commemorating the likes of Lincoln, Washington, King and other heroes of America. We also find this in Europe and in the countries of the East Asia such as China, where statues of Mao Zedong litter the country. Other common ways in which these heroes are commemorated are in public holidays, and the naming of public landmarks, ships, islands, or even planets.

(Read also: Have Africans Failed to Properly Curate Their Own History?)

African iconography has succeeded in commemorating a number of events and individuals across the continent’s history. While there are many physical structures celebrating illustrious people from the continent, Africa cannot compete with other continents across the world in the sheer volume of such sites. Whatever African countries are doing is ultimately insufficient when weighed against that of other places. The conclusion that logically follows these complaints is what Africa can do to be better. Some of these solutions such as breaking external channels of influence, discarding the unpleasant fledgling culture of neglect, and ending political corruption are obvious ones..

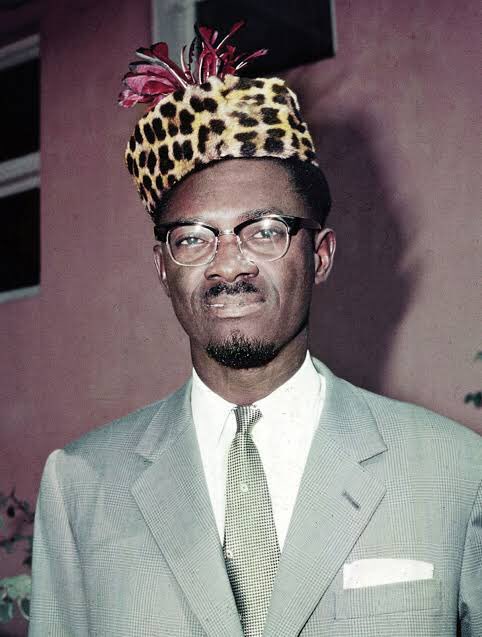

On the peripheries of history, there are controversial figures whose heroism and renown are downplayed by the perceived controversy surrounding their actions and death. Two such figures are DR Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, and Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara, whose legacy were demonised by an onslaught of foreign media vituperations that drove their various governments into a muted public regard for their legacy. On the contrary, the trumpets of these heroes should be blown loud and without restraint. Many such heroes who are spoken of with studied haughtiness litter the background of Africa. This issue also encompasses the destroyed or derelict structures from Africa’s antiquity. These are people who, by every standard metric, should be venerated relentlessly as key players in the histories of their countries. Africa must begin to choose its own heroes, heroes who are not determined by the haughty opinions of outsiders, but by a country’s particular understanding of its own history.

How, then, do we understand our history? We must open every avenue to discuss it and psychoanalyse our historical traumas. No aspect of history should be dissimulated in our education systems. Education systems in Africa must offer more than theories. They must be aligned to teach and foster the emergence of things greater than mere mediocrity, and thus gradually reduce our dependency on Western systems of education. We must be ready to look organically at who or what have been important to us in the long run. From this perspective, what was seen as full of ignominy in the past may become a crucial period of inevitable transition to greater things. An important case in point here may be the Women’s War of 1929 in Nigeria, which was known in colonial rhetoric as “Women’s Riot.”

This is perhaps why there is very little iconography anywhere commemorating the heroics of those women—an important inspirational aspect of history that highlights female power as unimpeachable—to serve as an example for African women today. On the contrary, similar events elsewhere in the West are branded “revolutions,” a prime in the West being the Albanian Revolution of 1997. In The Woman King, a recent Hollywood movie, the history of ancient Dahomey is depicted with some accuracy. The historical distortion is sometimes expected when African cannot tell its stories and allows others to do so. Perhaps Africa can do better with more indigenous efforts in the film industry on such a massive scale.

The Way Forward for Africa

A culture of neglect has developed in Africa after colonisation. The continent has allowed many of our historical artefacts, structures, and architectural iconography to fall into decay. This is a major problem being experienced by all spheres of African societies. We can point to, amongst other similar cases, the over a century old Douglas House in Owerri, which was demolished by the government of Nigeria’s Imo State in 2014 after a fire destroyed a part of it.

There are other such examples across Africa, including many derelict monuments and historical structures in the city of Johannesburg. Again and again, we are confronted with this common problem of carelessness and philistinism. There is always a tendency to allow great architectural and infrastructural feats to go into decay, helped in no small way by a succession of individual governments that share disparate values. While the disregard for culture and history persists, African countries can do better by establishing independent funding channels for these structures while decentralising the maintenance of monuments and creating avenues for transparency. There are many national museums existing in Africa today, but the long neglect being suffered by some of them shows that the current practice of building mere physical structures may not be sustainable. The countries of Africa must develop or find IT-enabled solutions to museum sustainability.

A culture of neglect can also be found in the lack of recognition for important people in past and contemporary history. This neglect fuels what is known today as the “brain drain” when people who have made, or about to make, monumental strides for themselves and their countries are not recognised by their own countries. It fans anger and unrest when this neglect perpetuates legacies of corruption and bigotry instead of rewarding real patriotism and dedicated contribution to a country’s image. A country that fails to recognise its real protagonists will not be able to export its own culture properly. Heroes preempt respect for a country at the international stage. The celebration of heroes is a way to retain future heroes to contribute to their countries’ development.

(Read also: Despite Strict International Laws, Challenges Abroad, Young Africans are Still Crossing Borders)

Today, Africa is experiencing the migration of its citizens to other parts of the globe. Africa must rise up and examine the lack of inspiration its citizens often get from their countries’ treatment of heroes. Recently, there has been debate as to why African scientists are not winning the Nobel Prize for the sciences, and some have wondered whether this is not linked to the near-neglect Africa accords its important figures, such as scientists, who are subsequently forced to move abroad. Stella Adadevoh, the Nigerian medical doctor that prevented Ebola virus from spreading in the country, should, for instance, have a major virological research institute named after her. Another exemplary case here is that of Nigeria’s Dr Ezekiel Izuogu, who created the Izuogu Z-600 car in the late 1990s. African countries cannot arrest such great losses of individuals if it does not first create institutions that encourage individual heroism in the sciences and arts, through education and proactive government policies, including grants, tax waivers for innovations, amongst other important programmes.

To be more effective in the commemoration of its heroes, African countries must end corruption in government and other sectors of national and private interest. When there is an absence of corruption, heroes can get their due. For instance, unsung heroes such as the millions of pensioners who have diligently served their countries into their old age can deservedly get their gratuity and pensions. Transparency is the foundation for encouraging innovation. Transparent governments in African countries will eschew platforms that project favouritism and establish genuine structures for talents to thrive in their striving to become heroes in their fields. The absence of corruption will also help create more iconography that enhances the prestige and values of African societies and subsequently be able to maintain such structures for the benefit of posterity.

Again, is Africa celebrating its own heroes enough and creating lasting legacies in their names? African governments must sit up with hard focus and define their political trajectories without bias. To be able to confront the future, Africa must celebrate the positive aspects of its past and highlight its negative past, too, for posterity to learn from. It is this awareness that partly drives development and helps to halt the loss of Africa’s human resources. Africa must then reorganise its political and educational structures to recognise heroes more.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.