As a boy living in the rectory attached to the church, Nduka did not immediately pick up the piano. His yearning to play music had led him to the music instrument store in the church. He picked up the trumpet and tried to blow into it but abandoned it when he felt pain on the edges of his mouth…

By Chimezie Chika

I

Echezonachukwu Nduka tells a very striking story of the crucial moment in his life when he discovered music: the church choir was practising for the upcoming dedication of the church on the 27th of December, 1995, and as he passed by the open doorway, he was struck by the vocal crenellation of quick rising sounds following each other, rising and falling in a carefully calibrated tempo. He stood there, outside the church building, unable to move, and in that moment of luminous clarity, he felt his soul climb and hover over all the surroundings, and he saw the beauty of the world and the grandeur of the years ahead. Years later, he would find out that what he had heard that day was the chorus of an oratorio from Handel’s Messiah titled “Lift Up Your Heads.” This epiphanic initiation into formal classical music would be, perhaps, the most defining moment in Nduka’s life, for herein was the discovery of a thing so elemental and celestial that it destabilised every other thing that happened prior.

Born on July 19, 1989, to parents who were Anglican ministers, Nduka grew up in the vicarage. His family moved around a lot in the nineties as a result of the several transfers his father was subject to. He recalls brief sojourns in places such as Oko, Agulu, Umunze, and Awka. His family stayed longest in the college town of Oko, and most of his fond memories of childhood, including his fateful encounter with classical music, took place there. The family he grew up in was normally involved in the daily rituals of prayer and music, and this shaped his thoughts. The proximity of the living quarters to the church deepened Nduka’s immersion in music, for his ears were constantly assailed by the polyphonal sounds of choir rehearsals.

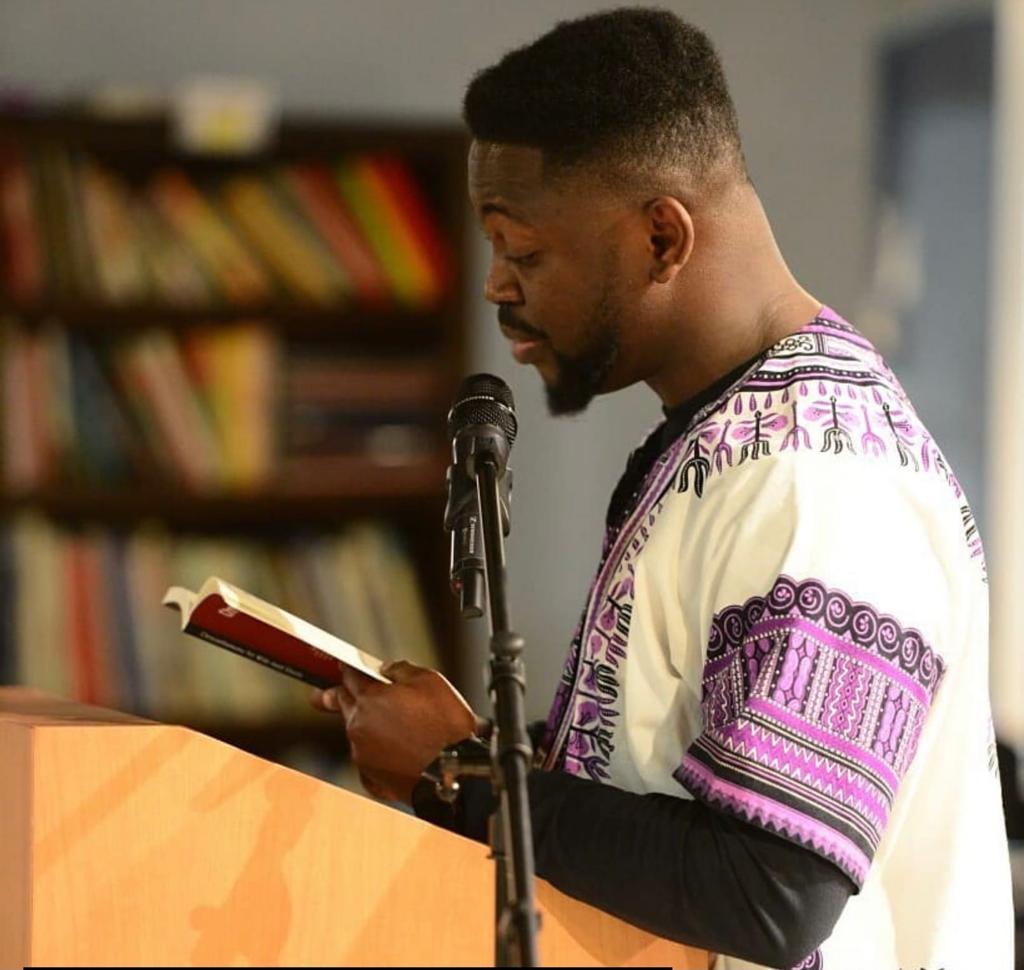

From the age of eight, at the encouragement of his family, Nduka began to take Bible readings in church. A stool would be placed for him to climb onto so that the congregation could see his head from the pulpit as he read the verses of the day. Nduka credits this as his first training in stage comportment, an etiquette so important in the performing arts. His family also encouraged his foray into music. In those early years, he began to go close to the choir, learning all the liturgical hymns by heart. In the brigade, which he joined around the age of five, martial music was mostly played. He was only too happy to experience music in all its eclectic forms.

In 2000, Nduka gained admission into the prestigious Bishop Crowther Seminary in Awka. It was here that his musical penchant blossomed under the tutelage of his music teacher, Amaka Igwe who taught him to read staff notation. He was in the school choir and was especially involved in the debating society; representing the school in state and national competitions. Nduka’s debating prowess is an early indication of his ability to express clear thoughts in words.

Playing the piano in church and in school, Nduka felt something akin to the levitation of the soul. He was completely at home with the riot of his fingers scurrying across the keyboard. In his quiet time, he imagined a music orchestra, performances, huge organs with storied keys reverberating through a hall; he heard crystalline tonalities in the mundane. It was this almost spiritual hankering for sounds that led him to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka for his bachelor’s degree in Music.

It was at Nsukka that Nduka deepened his knowledge of music. He learnt the long historiography and theory of music down to its present practice. The combination of his passion and practical engagement helped him advance his expertise in the different forms of classical music. Upon his graduation in 2010, Nduka was auditioned by Enoch Bibama, head of Viscount Organs Nigeria, for a position at RCCG in Ikeja, Lagos. He got the job and signed a three-month contract. It was his first professional contract as a pianist, barring small-time gigs he had taken before, and it set him on the path to making a career out of music.

As a young graduate, this seamless transition into the professional practice of music put him at a certain pedestal in which he saw his future laid out before him. He had no illusions regarding what he wanted with life or the great sounds that would reverberate from his hands.

II

Echezonachukwu Nduka talks about his introduction to African composers while at Nsukka. His piano teachers, Dr A.O Adeogun, and Prof. Christian Onyeji, formally introduced him to the work of African piano composers who, starting in the early fifties, sought to create a musical genre that merged certain aspects of western classical and indigenous African music. Thus, African Pianism was born. “Notwithstanding the work I have done with the music of African composers, classical music is still not a very well-known music tradition in Africa where people mostly want to dance and not sit still in a concert hall,” Nduka laments.

In many of his performances of African composers, one spots a sprightliness in the rhythm, almost like a formalised calypso. In his performance of Fred Onovwerosuoke’s “Jali” from 24 Studies in African Rhythms No 5, the sound dances over each other in a polyphonic progression. Varied rhythms go back and forth until they seem to achieve a harmony of emotion. His performance of Itunu Oyewale’s “Atewo” shows a formal mastery of the tenets of absolute music. Here, Nduka’s pianism is a striking fusion of African and Western classical sounds. As he touches the piano in rapid movements, there are many percussive sounds competing for attention in the upward movement of the argument, something akin to motetical complexity, until they reach a panicked intensity in the climax.

Nduka’s national service posting came up as his contract at RCCG expired. In 2011, he was posted to a private secondary school in Bungudu, a small town near Gusau in Zamfara State, where he taught Introductory Technology. He narrates how he immediately took up residency at the Cathedral Church of Christ, Gusau, partly because of his fear of the insurgency in most parts of northern Nigeria. He remembers the barren stretches of lands, the cultivated plains, and the bucolic air of Bungudu. He threw himself into the activities of the cathedral church in Tashan Magami, Gusau where he had an enthusiastic community of Christians around him, serving as the music director and organist of the church. Six months later, he redeployed to Owerri, Imo State. “Apart from the church in Gusau,” he says now, “I didn’t feel at home in the north. The bishop at the cathedral was sorry to see me go.”

In Owerri, he was posted to the Alvan Ikoku College of Education, serving in the Department of Music. This was a very pleasant time for him. Apart from his pedagogical duties at Alvan, he went on many paid concerts as a pianist and organist and had ample time to drive around most of the south-eastern parts of the country in his car, which he had bought shortly before his posting to Zamfara State. He read a lot of books and poetry at this time, attended literary events all over the east, and began to scribble lines of his own.

After his national service, the Department of Music retained him. At 23, he was probably the youngest lecturer in the school. Whenever he entered a class, students often mistook him for one of them. His early interest in music had buoyed him up the staircase of life, so that when he looked back he saw his peers casting about in the foliage of their dreams, seeking for the same purpose he had found early. There is research evidence to support the claim in some quarters that exposure to classical music enhances the cognitive and spatial reasoning of a person for short periods. If this is the case, then it is possible that classical music enthusiasts would not only feel things more deeply but also have a greater perception of things, a sudden moment of clarity.

III

The music suddenly comes to a stop for a second or two; a moment of silence, almost imperceptible. Then the thump of a shrill key. Then an answering bass salvo, the sound jarring the mind to awareness. The shrill note comes again and the bass salvo follows again. Like that, the music picks up. Higher note upon higher note, polyrhythmic sounds murmuring behind the major notes, like a rumba on a beach, an evening song, a festival. The counterpoint climbs, alternating between the drum-like sounds and the classical notes of the first salvo. The listener’s emotion surges with the music. He imagines an evening beach, the waves, the coconut palms, belles dancing.

Such is the sonic beauty of J.H. Kwabena Nketia’s “Volta Fantasy” as played by Echezonachukwu Nduka. The effect at a point is that of a modified contrapuntal fugue subsumed in African rhythms, the flute-like notes in-between almost like a lullaby. Nduka’s mastery of this complex network of sounds did not come easy. He says, “You have to work alone.” He is not only referring to music here but also to poetry and its demands for perfection.

As a boy living in the rectory attached to the church, Nduka did not immediately pick up the piano. His yearning to play music had led him to the music instrument store in the church. He picked up the trumpet and tried to blow into it but abandoned it when he felt pain on the edges of his mouth. His fingers took to the piano instead. In his essay, “Redreaming the Sound,” he tells the story of how his determination and hunger led him to teach himself to play the piano. Again he was greatly encouraged by his parents. His mother had a hand in the purchase of his first toy piano. Shortly afterwards, his father bought him his first real piano. In the ensuing years, he studied his favourite western classical composers vigorously. He was entranced by the works of Handel, Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Schumann.

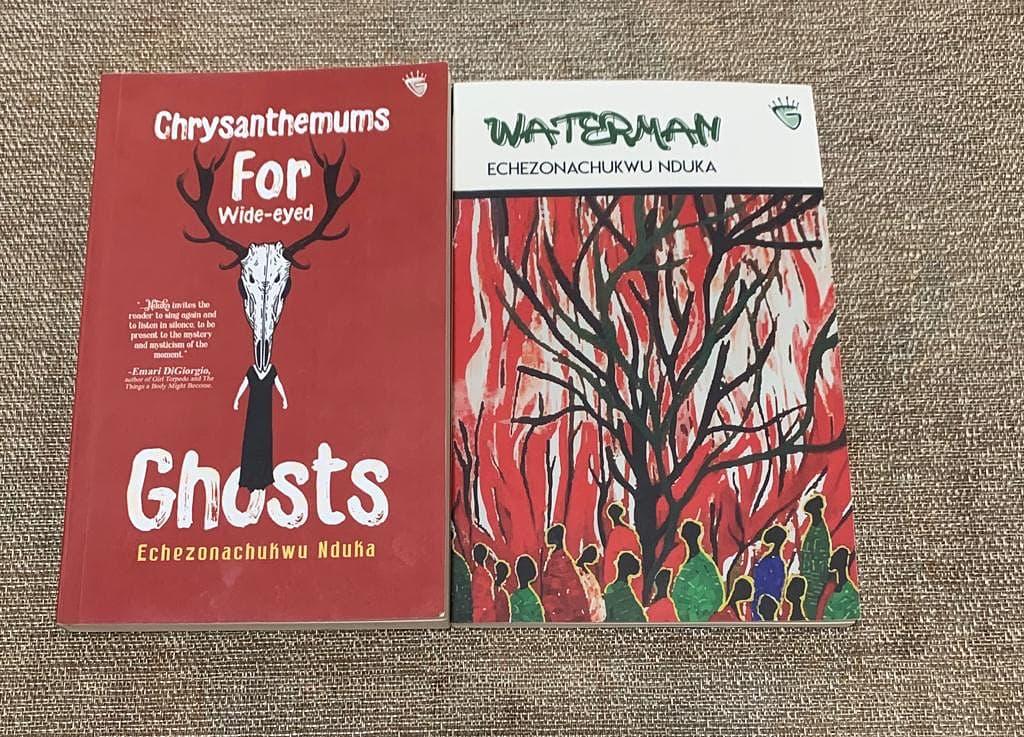

From 2012, Echezonachukwu Nduka began to publish his poetry. His first publication gave him a certain sense of achievement, so that he was motivated to write more. More publications followed in prominent journals such as Transition, Jalada, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, amongst others. Though poetry came late to him, the propensity to write came from somewhere deep down his subconscious. When he observed people and places, he wanted to express the encounters, the sights and scenes. Sometimes, he felt an emotion that music did not completely own. Poetry was his way of making sense of these things. His ecclesiastical upbringing placed him in a chastising relationship with life and death. In other words, one must live well in order to experience celestial bliss in the afterlife. Much of his first collection, Chrysanthemums for Wide-eyed Ghosts, confronts death and memory. One of the poems in the collection, “Inside the Old Room,” deals with death as an examination of memorabilia. Here, furniture, books, and pictures become mnemonic items to remember the dead. “Photographs in monochrome are placed on a shelf,/their images staring longingly like a lonely lover awaiting/familiar laughter . . .,” he writes. The poem is a highly lyrical quintessence of Nduka’s standard preoccupations of death, memory, music and faith. In one striking imagery, he muses: “There is no one left to say the angelus, none to measure the size of silences.”

Music permeates Nduka’s poetry. Since he came to music before he began to write, his poetry was greatly influenced by it. This was, after all, the poet who wrote that “To kill a song/you must find its spirit/and pin it to the wall.” What, then, is the spirit of song, and how connected is it to the spirit of poetry? One can only go back to the essence of art to find answers.

Sometimes the description of an emotion in Nduka’s poetry is better understood with the knowledge of the musical reference between the lines. We see this in “Ghost Lover” from Chrysanthemums and also in “Arabesques” from Waterman, his second collection of poems. The structure of some of his poems are tailored to mirror classical music. Some poems progress from the first movement to coda. There are poetic sonatas and lyrical ensembles. There are poems imbued with rhythms. There are choruses and there are arias and oratorios. The entirety of his first collection is structured like the seven movements of a classical music piece.

IV

Echezonachukwu Nduka plays music before he sits down to write. He mentions the powerful effects of Tchaikovsky’s “Piano Concerto” and Beethoven’s “Piano Concerto, no 4 & 5.” He also reads Ben Okri’s essays to put him in the right frame of mind.

While still lecturing at Alvan, Nduka gained admission to Kingston University, London to pursue his master’s degree in Music. His time in London was mostly spent in studious seclusion, but he also acknowledges that his experiences there influenced his writing in terms of cultural and racial awareness. “I did not really write my MA thesis in classical or African piano music as one would expect,” he says now. “I chose to write a critical thesis on popular music.”

Nduka’s range in music came in handy when he moved to the United States in 2016. It was in America that he began to gain greater acclaim as both a classical pianist and a poet. He gave numerous lectures and concerts and was featured in international radio and television. His first two collections of poetry were published after he moved to the US. He also released his first two EPs: Choreowaves, which the BBC Newsday described as a “unique audio fusion,” and Nine Encores, his second self-referential EP which includes western classical music and the African pianism of composers such as Joshua Uzoigwe, Fred Onovwerosuoke, and Christian Onyeji. Nduka’s unique perspective is to project African piano music compositions and to create a conversation between them and the western classical music.

Amidst all these activities, Nduka reveals that he has a classical music concert coming up in February next year. Nduka has also been awarded the prestigious Benjamin Franklin Fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania to pursue his doctoral research in the ethnomusicology of African pianism. One thinks of Nduka’s optimism in terms of water, its life-giving pervasiveness. Perhaps that was the overriding imagery that influenced his second collection of poems.

While writing Waterman, Nduka had listened to Schumann’s “Piano Concerto.” This may account for the roving emotional tone of the book. Like water, the collection shimmers with light. In the eponymous poem, he writes that “waters take inventory of trespassers in cryptic tongue of air,” defining the metaphorical thrust of the book.

V

Echezonachukwu Nduka is interested in the reinvention of language through music. He has stated that he was first a “listener” before he became a “reader.” When he goes out, his ears pick out emotion in random sounds. To express a thought, he thinks of it in terms of sounds. All his strongly-felt emotional moments are subsumed in the memory of music. He has written movingly of how, while listening to Stephen Adam’s “The Holy City,” he remembers his late mother, her funeral service, and the crippling sadness that enveloped him. And yet the music makes him long for that memory. The poetry that expresses these emotions involuntarily acquires the rhythmic entrainment of music.

Again the question must be asked: what is the spirit of song and how is it connected to the spirit of poetry? In one instance, Nduka points to the “emptiness” of derailed dreams, like the subject in the poem “Mahler,” from Waterman, who has “a piano waiting in his room, cold from neglect.” In another instance, in “Transition,” he points to unrestrained freedom that is often the case with the creation of art: “Oh harmonic resonance of all unguarded hours,/ride me to the precipice—”

Let us look at Nduka’s most recently published poem, “Jazz Abibiman.” Here, the poem follows the rhythm of jazz delightfully, looping and turning, sometimes jarring, sometimes slowing to sink in an image. Here, “the sound is vast enough to recollect . . .” histories and tears. In mapping Black and African histories, the story “opens with a guitar solo. Synths/ & hi-hats set the tone for rebirth.”

The perfect fusion of music and poetry is unrelenting: the government is “alte,” and the teeming electorate are “a chorus of voices,/throbbing feet, reeds of horns . . .” The story continues in the same striking cadence. Like the gory events of October 20, 2020 in Lekki, Lagos, the despotic regime demand a song from the youth. The young people chorus: “When we sang, our country turned its/back & walked away,/feet dripping with blood . . .”

The image of national disappointment is embodied in the intensity of expression of the rambling jazz. At that moment, life acquires forlorn rhythms and the music becomes poetry.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Praxis Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment.