Advancing technologies, receptive studios, and the collaborative efforts of producers, artists and storytellers have breathed life into this burgeoning industry…

By Sybil Fekurumoh

Africa’s movie industry, like its music industry, has gained global traction in recent years. Africa’s animation industry is setting a new frontier for storytelling and entertainment, both locally and internationally. African animators are spreading their tentacles into the far reaches of the global industry. In the animation industry, there’s been a steady rise of creators and animation studios who have evolved their crafts to create films and series on their own terms. These films tell authentic African stories, with shared experiences Africans can easily relate to at the forefront.

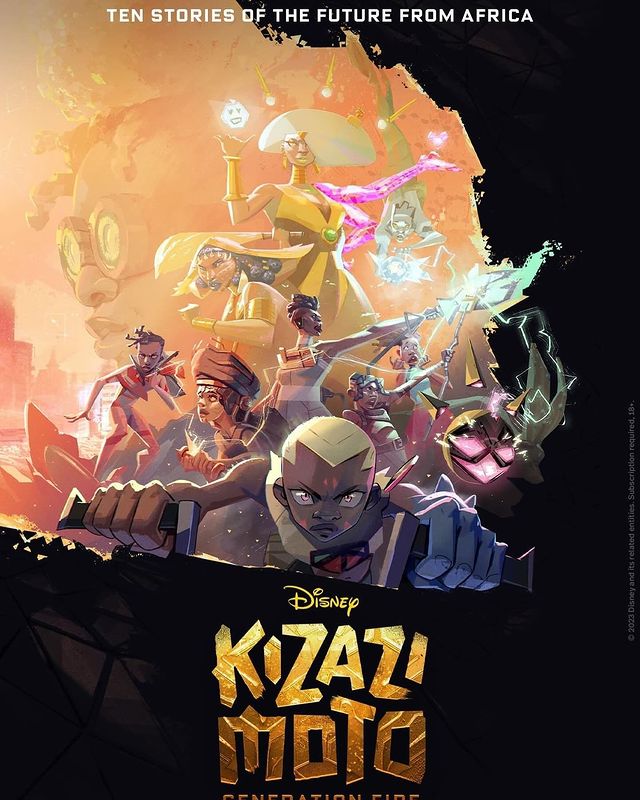

Only this year, there’s been much buzz about the line of animation projects making their way to streaming platforms. Since Disney+ announced the premiere date for its Sci-Fi/African animated anthology, Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire, the series has been generating excitement, and on July 5th, the animated series was released on the streaming platform. This excitement is to be expected. Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire encompasses the collective effort of creators from Zimbabwe, South Africa, Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, and Egypt. Also, this original ten-part series takes on several themes that are sure to resonate with viewers, exploring themes such as the influence of social media, colonialism, coming of age, friendship, and service, among others. But most importantly, the anthology is inspired by Africa’s diverse history and culture, told from an African perspective.

Netflix also announced the premiere of Africa’s first animated series, Supa Team 4, set for July 20th. The series follows four teenage girls living in a futuristic version of Lusaka, Zambia, who are recruited by a retired secret agent to save the world. Netflix acquired the animated series in 2019, as Mama K’s Team 4, produced by Zambian screenwriter Malenga Mulendema. Supa Team 4 was groundbreaking, as Africa’s first animated series. Also, the series’ all-women crew as superheroes further pushes the boundaries of representation, as it breaks away from the stereotypical portrayals of African women in film. This comes after Showmax aired the made-in-Nigeria animated series, Jay Jay: The Chosen One, inspired by the Nigerian footballer, Jay Jay Okocha.

In addition, Cartoon Network is set to debut its first superhero animated comedy series, Garbage Boy and Trash Can, produced in South Africa. The series, which will premiere on Cartoon Network Africa on 17th July, 2023 is created by Nigerian animator, Ridwan Moshood, who won the 2018 CN Creative Lab initiative. In the face of the seemingly ludicrous concept of Garbage Boy and Trash Can, young Tobi, a self-proclaimed superhero, fearlessly embarks on thrilling adventures, alongside his loyal sidekick, triumphing over adversities along the way. Last year as well, HBO Max and Cartoon Network announced a 2D animated adaptation of the graphic novel series, Iyanu: Child of Wonder. Written by Nigerian-born author, Roye Okupe, the story is inspired by Yoruba culture, making references to its folklore, music, and tradition. Interestingly, Okupe’s comic collection, Malika: Warrior Queen, which is set in fifteenth-century West Africa, and follows the exploits of the titular queen and military commander, Malika, was adapted into an animated short film.

(Read also: Iyanu: Child of Wonder HBO Adaptation: Nigeria’s Animation Industry and the Nigerian Factor)

Oftentimes, cartoons and animations are thought of as popular entertainment for children, as something of a pasttime or a distraction from hyperactivity. Granted, there is some truth in this, but like traditional films or any other visual media, animations are an integral part of communication. Creating animation is a complex art form, yet it conveys important messages in simple ways. Creators can tell unique stories in a readily comprehensible manner, enabling audiences of all ages to learn, delve into possibilities, and perceive the world through a fresh lens. African animations bring African stories to life, allowing storytellers to portray the nuances of African narratives to global audiences. The futuristic and abstract elements serve to ignite curiosity and wonder, enticing individuals to venture into unexplored narratives and controversial subjects, while also imparting valuable lessons. Iwájú, another anticipated Disney Studio production in 2023, is set in a futuristic Lagos, Nigeria, and features themes of inequality and class divide.

The futuristic and exploratory elements aside, these animations also evoke a comforting sense of familiarity for viewers. The significance of representation cannot be overlooked, as the relatability of these stories — through the inclusion of familiar names, history, beliefs, and cultural references — strikes a chord with audiences. Nigeria’s first feature-length 3D animation, Lady Buckit and the Motley Mopsters, received critical acclaim, not just for being the first of its kind in Nigeria, but also because it represented South-South Nigeria and showcased the Niger Delta to a global audience. As Nigerian independent animator, Kemi Esther Gbadamosi, shared with Afrocritik, there is a need for cultural animation projects that explore Africa’s distinct cultural interactions and elements. She noted that, “It’s really about our unique experience and perspective different from the rest of the world.” Gbadamosi’s project got featured at the 2023 Berlinale Film Festival.

(Read also: Kemi Esther Gbadamosi on Taking Nigerian Animated Films to Berlinale: In Conversation with Afrocritik)

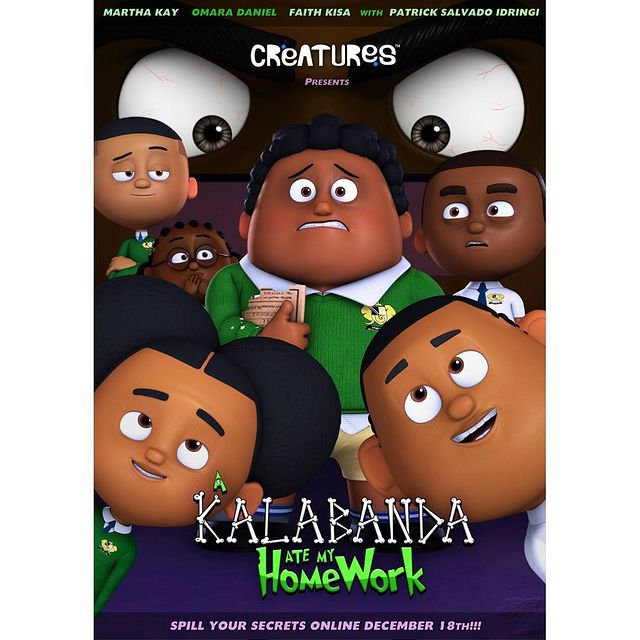

In the 2017 Ugandan animated short film, A Kalabanda Ate My Homework, created by Raymond Malinga, Tendo, a primary school pupil, comes to school without his homework. His excuse, a Kalabanda ate his homework. The film is a Ugandan twist to the Western reference, “a dog ate my homework” and has an appeal because, in Ugandan urban legend, the Kalabanda is a mythical creature that hunts schools. It is similar to the Nigerian “Lady Koi Koi” myth featuring an evil woman who is believed to lurk in boarding schools. Unsurprisingly, A Kalabanda Ate My Homework received several awards and nominations and was screened at the 2018 Cannes Festival. In a TED Talk, Malinga, who is also the CEO of Creatures Animation Studio in Kampala, talks about the possibilities of African animations, “…these fictional worlds [of cartoons and animations] can play a pivotal role [for young people] if they depict familiar people in familiar environments, experiencing familiar problems, and providing extra-ordinary solutions that are yet to materialise in the real world.” As these animated films depict Africa’s indigenous histories, or a more technology-driven future for Africans, young Africans can connect with their past, and perhaps visualise innovative solutions for the future.

The successes of animators extend beyond the global stage; these creators are also garnering well-deserved recognition as film creators within their own local communities. Nigeria, for example, has witnessed an increase in animation produced in the country, such as the 2022 production, Moremi: The Epic Battle, inspired by the historical Queen Moremi of Ife, and Anthill Studios animated series, League of Orisha. Similar to how books and literature possess the power to expand one’s horizons, films, as an art form, have the capacity to inspire, and animation is no exception to this potential.

African audiences have long yearned for animated stories that reflect their own experiences and feature characters who share similar features. Unfortunately, there has been a scarcity of such narratives. Many young adults today reminisce about their childhood cartoons, which predominantly showcased superheroes, princes, and princesses who were far removed from their own realities. The creative industry recognised this unmet demand, and seized the opportunity to create animation stories for African viewers. Advancing technologies, receptive studios, and the collaborative efforts of producers, artists and storytellers have breathed life into this burgeoning industry.

The industry still faces a significant shortage of animators, which limits its potential. Animation demands specific skills and training, which may not be easily accessible in Africa. This, combined with structural constraints and a lack of government incentives, hampers the industry’s growth. While international streaming platforms, channels, and festivals have provided a substantial boost to the animation sector, it is hoped that this progress will encourage the government and local organisations to invest more in the industry’s development. Despite the many numerous challenges confronting the African animation industry, the commendable strides made by African animators and creators internationally, have both impressed and fueled the desire for even greater achievements.

Sybil Fekurumoh is a senior writer for Afrocritik. Connect with her on Twitter and Instagram at @toqueensaber.