…the sentiment of migrating is not shared by all young adults, and most are still optimistic about Nigeria…

By Sybil Fekurumoh

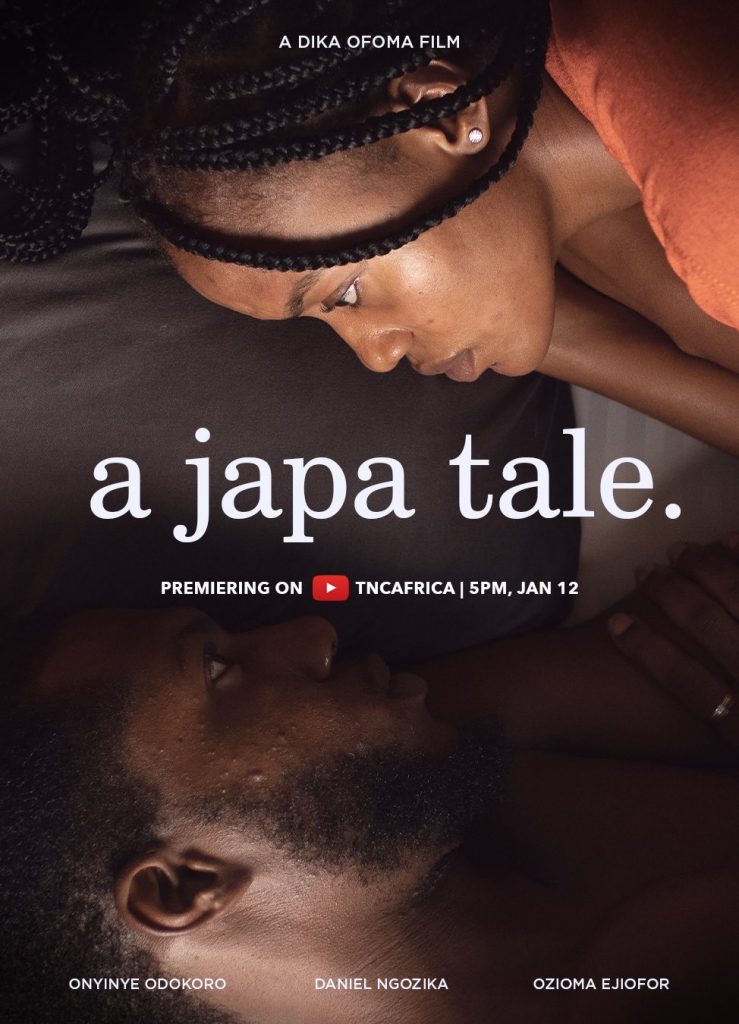

In less than thirty minutes of its run time, A Japa Tale lets viewers into the little-discussed side, if ever said, of migration. “To japa,” which loosely translates as “to run away” is a familiar term in the parlance of young adult Nigerians aspiring to leave the country. In most cases, the side of a migration story that we get to witness is the celebratory moment when one successfully departs, the part where observers look on with admiration that a person finally “got out,” and the part where we get to aww at the pictures of departees welcoming themselves to “new dispensations.” But with the Dika Ofoma-written and -directed short film, viewers peer into the people and relationships that departees leave behind, and the sacrifices and emotional toll that migration may take on intending departees.

https://youtu.be/FbuxNfo6BFM

A Japa Tale follows the stories of two lovers, Emuche (Oyinye Odokoro) and Dubem (Daniel Ngozika), as their relationship becomes more complex when one party decides to leave the country. A Japa Tale is sewn from the same fabric as the 2020 Esiri brothers-directed movie, Eyimofe, as both films explore migration and the need to escape to find seemingly greener pastures. But unlike Eyimoye, the characters do not settle for what is available, but instead, make decisions based on what they think they deserve. When Dubem suddenly announces his plans to leave the country, Emuche finds out she’s pregnant, too. Acting on a whim, Dubem suggests they get married and have his girlfriend move in with his mother (Ozioma Ejiofor) temporarily. In theory, it is a straightforward plan, but this plan is rather simplistic, and reality is as complicated as it gets. As prospective parents, marriage is the logical step to take for their unborn child. Perhaps they could have tried to have the child abroad, too. This would mirror the plot of the 2010 movie, Anchor Baby, where a young illegal migrant couple tries to have their baby can become a US citizen. But we never get to see this happen in A Japa Tale; Emuche doesn’t join Dubem abroad, and it’s hard to tell whether she ever does.

At first glance, one is tempted to dislike these characters; a girlfriend seemingly afraid to commit, a boyfriend that gives off important information at the last minute and can’t seem to make up his mind, and a difficult-to-please, soon-to-be mother-in-law. But A Japa Tale moves away from a rather predictable trope and finely weaves us a progressive exploration of modern young adults making decisions and coming to terms with their choices. It is a refreshing narrative of growing and living in Nigeria.

But A Japa Tale is a story about love and migration as it is about personal goals and aspirations. As observers, we are compelled to see this young couple, not as a whole, but as individual beings, as one would any young adult trying to make a name for one’s self. At its core, the movie reveals that right or wrong decisions are not polarised, that truth can be subjective, and there are grey areas that one must also consider. We can empathise with the conflicted Dubem, as much as we can with other young professionals in Nigeria, as the economy bites at their seams and leaves holes in their pockets, so much so that leaving the country becomes the only available option. Despite rising prices in ticket sales for air travel, last year, reports showed travel by flight increased by 91% in the second half of 2022, as young professionals in Nigeria leave the country for better opportunities abroad. Dubem, as a doctor, joins the exodus of medical practitioners who have decried poor working conditions in Nigeria, to practice abroad.

(Read also: Despite Strict International Laws Abroad, Young Africans are Still Crossing Borders)

Again, the audience can perceive the unfair disadvantage of the female protagonist, Emuche. While the male counterpart is encouraged to be ambitious, it is not so much the same for women who choose ambition over motherhood. But Emuche is daring enough to weigh her options on a pedestal, and even when her ambitions are scoffed at, we can see the conviction with which she reminds herself that her dreams, too, are relevant. The dynamics of a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relationship that is often projected on the screen is one where two women are pitted against one another. But instead, we see a loving, supporting, and understanding mother looking out for her son. That is what family members do after all, they look out for each other. We see this selfless care in another migration story, Ijé: The Journey (2010), where a woman willingly crosses borders to defend her sister who has been accused of a crime. She sought the truth and fought for her sister’s freedom, amidst a corrupt judicial system. As this is less a review and more of an observation of the parallels between A Japa Tale and real life, it is difficult to point out where this movie falls short. If there are any, the excellence of the storytelling would make these shortcomings forgivable. As with many older adults, we see a mother that is aware of the changing times and modern ideologies even when she cannot fully grasp these beliefs. Essentially, Ofoma’s characters are informed and cognisant enough to understand each other’s decisions, even when they do not accept said decisions.

In a few sequences and dialogues, the movie also interrogates the continuing discourse about abortion rights and pro-life choices. As much as children are culturally viewed as blessings from God, we see a young woman whose trajectory is about to be changed by an unplanned pregnancy, and perhaps for a split second, we do not consider Emuche’s contemplation as an act of selfishness, but rather, a young woman saving herself in uncertain times. The movie comes to an end and the credits roll in, but the story is hardly finite, and Ofoma also allows his audience to speculate the boundaries and intersections between actions, religion, and beliefs. For example, abortion is hinted at in the short film, even as it is a tentative subject in Africa, for religious and/or cultural reasons. Unless performed to save the life of a pregnant woman, abortion remains illegal in Nigeria.

Yet, Dubem’s mother, a consistent churchgoer and practicing Catholic hints at abortion, yet, her son, who barely practices the religion and engages in premarital sex vehemently discourages it. Perhaps the mother understands the challenges of bringing up a child as a mother herself and considers the alternative a worthy-enough compromise, and Dubem’s reaction mirrors people making assertions about things they cannot fully understand. There is also the question of navigating a long-distance relationship, where sometimes distance makes the heart grow fonder, and other times, it becomes a deal-breaker. Dubem could go off the radar and appear in 25 years to reclaim his love, Emuche, who might have moved on from the relationship as the story went in Gone (2021) where a husband disappears without a trace in New York, only to reappear after 25 years to pick up the relationship where he left off. Sure, that may only happens in movies, but there is a joke about the proximity between the two couples that determines whether the relationship would work. A long-distance between a couple in Nigeria would no sooner collapse compared to when one party is out of the country.

(Read also: Abortion Ban, and the Fate of African Women in the US)

I couldn’t help but also notice the little details; a doctor’s need to give a lesson now and then on “cavity protection,” an aspiring actress reading the works of Constantin Stanislavski. There’s also tribalism and the subtle way tribal groups shade one another, and how older adults have a distrust for modern technology. The growing disinterest of the young adult population towards religion is right under one’s nose, or perhaps it is a growing interest in traditional religion, such as when Emuche says “I thought the gods were playing some kind of joke.” One is also never too old to be scolded by a parent, and we can all agree that talking about safe sex with a parent would always be a cringy discussion.

Also, the sentiment of migrating is not shared by all young adults, and most are still optimistic about Nigeria. Emuche doesn’t consider leaving Nigeria, she believes her dreams are achievable, too, in Nigeria, or it is likely that she pictures another country to be just as dire as hers, and a dream country is illusionary. Consider the 2021 migration movie, Flaky, starring Tinuke Adetunji as Ibinabo where Ibinabo soon finds out as a young migrant working a low-income job in the US that chasing the “American Dream” is a fool’s errand.

In A Japa Tale, the use of the Igbo language during communication is commendable. It adds to the realism of the film and gives it a natural, homely feel. You can easily picture yourself having a conversation with your family at home. One cannot quite place their emotions after watching A Japa Tale. The film’s unpredictability takes the viewer on a journey that is both thought-provoking and enjoyable. It is a heartbreaking story that is potentially a sad romance, but it is also a happy-ending film where the things that you wish could still imaginably come through. The short film is well-written and the characters embody their roles naturally and effortlessly. The film is a testament to the director’s skill and is a true representation of the quality of storytelling that can be found in the Nigerian film industry. It is a noteworthy production that showcases a unique portrayal of everyday occurrences in Nigeria.

(A Japa Tale is showing on the TNC Africa channel on YouTube.)

Cover image credit: Geralt from Pixabay

Sybil Fekurumoh is a senior writer for Afrocritik. Connect with her on Twitter and Instagram at @toqueensaber.