Fela was no gentleman; he used music as a weapon. He believed in a free Africa and had problems with authoritarian and military regimes. His activism was exemplary if often leading to violent outcomes…

By Chimezie Chika

Fela, Gentleman?

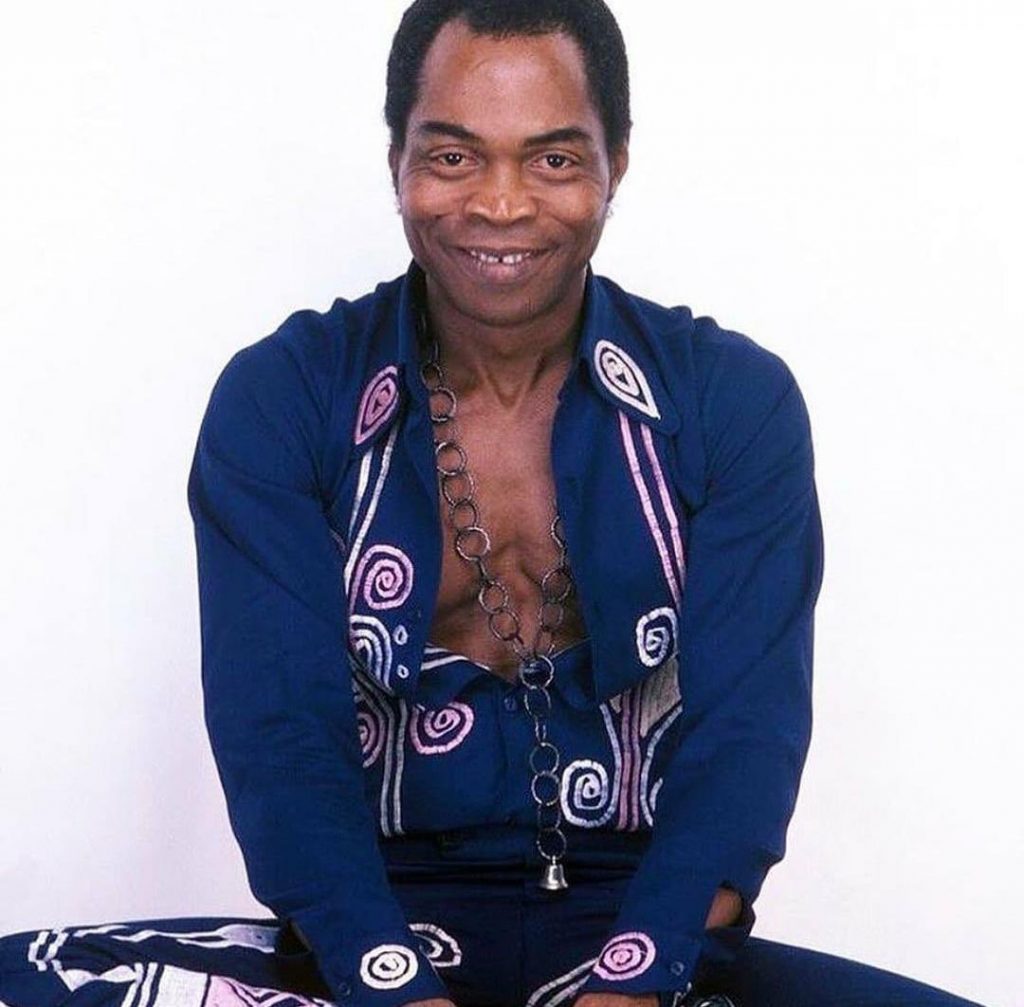

A scene in a video from the 1980s. On the big, green sofa sits a thin, sallow man in panties, his upper body bare, his hands splayed out before him in a relaxed posture. On his right hand, there is a joint which he brings to his mouth from time to time, inhaling deeply and blowing out wispy coils of smoke. He looks about him, smiling occasionally at no one in particular. He seems a little weary, too, as if he finds the act of talking a great effort. His posture shows he wants to be alone. All around him, many women and young men are walking to and fro, engaged in all manner of activities. But Fela Anikulakpo Kuti, the leader of the pack at his Kalakuta Republic residence—a quasi-socialist setup that also houses his dozens of women, band members, and disciples from all over Nigeria and the rest of the world, who come in and stay on—seems tired and weary, not wanting to talk.

Don’t be deceived by his silence. In 1973, this same man sang, I no be gentleman at all oo/I be Africa man, original/I no be gentleman at all oo. Just in case you were already about to mistake him for a gentleman. At the heart of those lyrics are his purpose and image of himself as a social crusader. There is certainly nothing gentle about a man that makes militant music about the injustices of military government, and all illegitimate political setups. Each of his sounds, his songs, are accompanied by a forceful personality consumed by a desire to scream messages against corruption in high places. In the discharge of this duty, he does not advocate gentleness. Gentleness, he points out, should be the least concern of a drowning African man fighting to save himself from the treacherous storms of his country’s political shortcomings. I be Africa man, original. I no be gentleman at all oo.

(Read also: Echezonachukwu Nduka and the Music of Poetry)

Fela was a man for whom dissidence was a way to speak the truth. His every action was couched in unconventional behaviour. For him, granite authority had to be discarded in favour of socialist equality. That was the hope of the African continent. He subscribed to the message of his hero, Kwame Nkrumah, who in the late 1950s and 1960s preached the message of a united Africa. Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism—alongside the black nationalism of Malcolm X, and the Civil Rights Movement in the United States in the 1960s—struck a chord in Fela. He realised, he said, that even in his desire for swashbuckling difference, he had been going about it all wrong. He was agreeing with the establishment by his own wrong footing. He sought to create a music that spoke to his new identity—music that is Africa in all flavours, music that is at once jolting in its message and arresting in its merging of sounds from Africa, Europe, and America. The music that Fela created, known today as Afrobeat, is an eclectic mixture of sounds from Yoruba music, jazz, African spiritual music and funk. Instruments ranged from drums of all kinds, both African and Western, saxophones, trumpets, keyboards, guitars, and other instruments from West Africa.

Fela had been brought up to become a gentleman. He came from a prominent upper middle class Yoruba family in Abeokuta, western Nigeria, consisting of his father, a church minister, and his mother, Chief Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, who was an educator, political campaigner, women rights activist and purportedly the first Nigerian woman to own and drive a car in Nigeria. His parents had careers planned out for their children, with expectations that they would become prominent ministers and leaders in the new Nigeria. With that in mind, Fela was sent off to England to get a degree in medicine. But the young Fela immediately drifted from the formalities of anatomy and physiology. Teacher don’t teach me nonsense, he must have said, and switched to a major in music at the Trinity College of Music.

Music as a Weapon

In an interview with Reelin’ in the Years in 1988, Fela tried to describe the unique form of music he had created: “The way I try to describe my music, it’s like I was born a colonial boy. I went to colonial school. I went to England to study music and everything . . . When I started working as a professional, I found later that I was not playing African music. I had to take myself back, find books to read, and started listening to a lot of traditional African music . . . this is my music . . . I told people that African music was going to be the music of the future . . .” Between his early days with his first band, the Koola Lobitos, who played in the London underground music scene in the sixties, and his epiphanic moment in the United States with Sandra Smith, Fela discovered that, as a black man, his music should have a deeper purpose and meaning. In his struggles to create something new out of this new belief, he began to see music as a weapon. In many interviews, he repeated this mantra: “Music is the weapon of the future.”

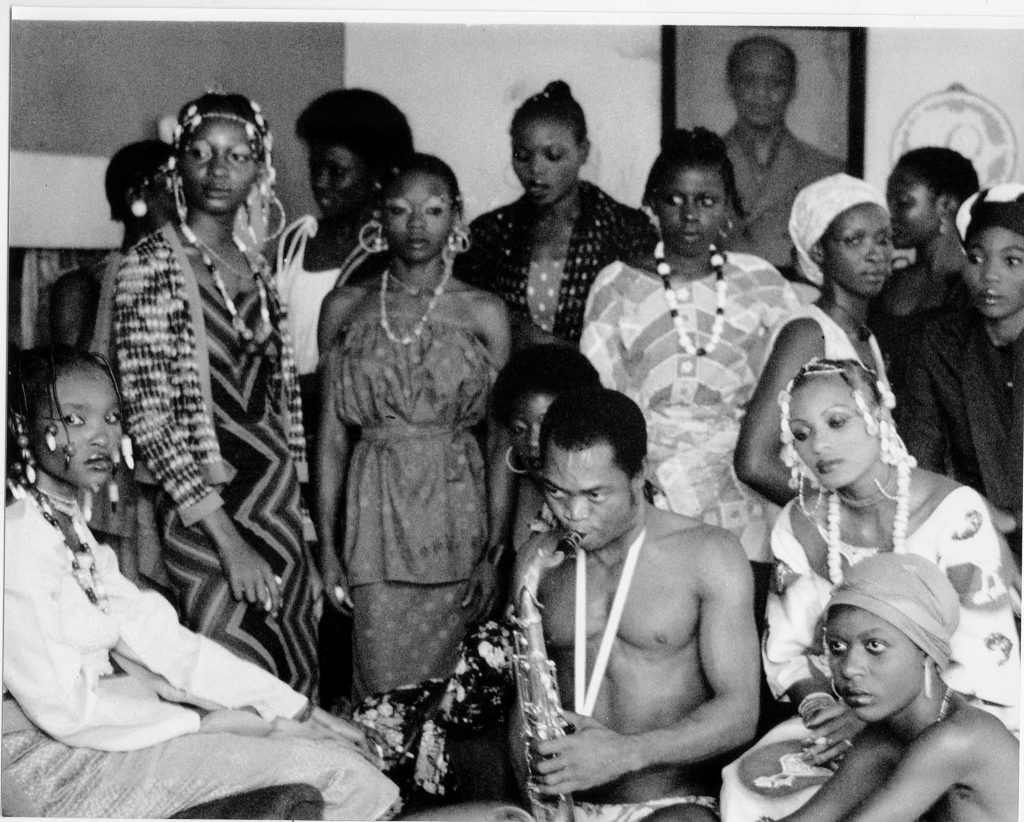

Returning to Nigeria in the 1970s, Fela reassembled his band as the Africa ‘70, established his Kalakuta Republic commune and declared it independent of the Nigerian state. He established his famous night club, The Shrine, where people from all over the world witnessed some his most electrifying live performances. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, The Shrine was so popular among young people that it served as a melting point of all budding cultural expressions and dissidence at the time. On international stages, audiences marvelled at Fela’s intense music—the enigma of the thin man twisting his body and mouthing angry lyrics on stage. The late 1970s through the 1980s was perhaps his most turbulent period. With his now aptly renamed band, Egypt 80, he got more direct in his music activism and suffered greatly for it.

But Fela had told us that music is a weapon. With it, he shot slings and bullets. No agreement today, no agreement tomorrow, he sings in the slow-burning blend of instruments and styles in “No Agreement.” There would be no love lost between him and the people he fought. Slings and bullets as lyrics. Dem steal all the money/Dem kill many students/Dem burn many houses.

Fela, Beast of No Nation?

Fela was a different beast, the likes of which the Nigerian government and its populace had never before seen. In his fiery, slightly protruding eyes, there was anger and defiance. In his bare torso, there was primitive daring. In his swanky moves on stage, his interjections into the jazzy groove of the saxophones, the drum percussions, the chorus by his backup singers, there was the determination to make music that defied tyranny—a music for the masses, the lyrical hope of the suffering multitudes. When the military juntas of his time sent soldiers into the streets to trample and subjugate the poor masses, Fela cursed them, beasts of no nation! When the leaders of the day were caught up in corruption scandals, Fela screamed, beasts of no nation! For he seemed to say, if you did this, then you’re all just animals in the forests, with no sense of duty to any nation. Curses and expletives were never far from the shores of the musical sea of Fela’s Afrobeat. Animal in human skin . . . Animal in craze-man skin.

At the height of his fame, Fela always had close brushes with the military regime in Nigeria, whom he criticised without restraint. He recorded “Beasts of No Nation” after a 20 month stint in prison between 1984 and 1985. The album was released in 1989, featuring the eponymous song. In the song, he spared no fine words for the military regime. The lyrics of the song from the beginning seemed to exude a laid-back anger, climbing slowly to the indignant lines: Human rights na my property/so therefore, you can’t dash me my property. Fela was referring to how authoritarian regimes pretend that releasing innocent prisoners was a way of doing them a favour.

In 1976, Fela released the album, Zombie, in Nigeria. The title song was a harsh criticism of the Nigerian military, whom Fela likens to zombies who move without thinking. Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go/Zombie no go stop, unless you tell am to stop. The military junta felt personally insulted by the song’s lyrics and stormed Kalakuta Republic in a 1000-man strong raid by the Nigerian Armed Forces. Fela was arrested, Kalakuta Republic was burned down and Fela’s old mother was thrown out of the window. She died after eight weeks of lying in a coma.

These events deeply affected Fela’s relationship with Nigerian society. In the aftermath, he would marry 27 of his backup singers in a single ceremony, claiming that the women could not find jobs after the destruction of Kalakuta Republic, and he felt an obligation to help them. But these actions only increased his notoriety and mystique in the eyes of people. In one bold act, he deposited his mother’s coffin in front of Dodan Barracks (Nigeria’s military headquarters) in a stand-off between him and the soldiers. In Fela’s metaphor, ‘beasts of no nation’ are the illegitimate military leadership and authoritarian regimes across Africa who often engage in human rights abuses. The metaphor, if we think about it deeply enough without the plural, could also be that of the one man fighting a dangerous war against gun-toting authority all over the world. He becomes a friend of no nation, for, in fighting, he becomes a lone beast with no biases to a particular nation, groups, or people; the one that says I waka waka waka/I go many places—a beast of no nation.

(Read also: Umu Obiligbo and the Music of Life)

Sorrow, Tears and Blood

Fela was no gentleman; he used music as a weapon. He believed in a free Africa and had problems with authoritarian and military regimes. His activism was exemplary if often leading to violent outcomes. But these were not all. Fela had an often turbulent and troubled personal life—the very picture of the same “Roforofo Fight” he sang about. He smoked incredible amounts of marijuana and had been known to praise marijuana as being medicinal. His sex life was littered with tales of orgies and legendary promiscuity. His large harem of 27 wives and concubines did not help his image in some quarters.

In his time, and years afterward, Fela was sometimes accused of having a bad influence on young people with his debauched personal life. Kalakuta Republic was accused of being nothing more than a brothel and a den for criminals and lawless people. This was the perfect excuse for the raids and arrests that mired Fela’s lifetime. His death from AIDS-related ailments seemed to confirm the accusations of his detractors and those who, even today, judge him harshly by his personal life.

Yet, is that all there is to Fela’s legacy? Perhaps, at this point, we can remember the sorrow, tears and blood of the downtrodden whom Fela fought for: the hungry children walking about in the streets, the masses of people who toil so hard and yet have so little to show for it, the helpless ones who are killed in avoidable wars. Perhaps we can remember the maverick character of the defiant musician who hated tyranny with all his might. For a musician of Fela’s peculiar talents and themes, he needed no softness or tenderness; his dissident character had served him well in his career. Here was a man who had gifted the world a timeless oeuvre of songs and a musical genre that will endure, perhaps forever.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.