With Nollywood films becoming more popular than ever, it would be very interesting to see Nigerian theatre leverage on the film industry in re-establishing itself as a worthy vehicle for leisure and information…

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

Between the 1930s and the 1950s, Hollywood fell in love with Broadway. Filmmakers scrambled to produce hit musicals, employing Broadway songwriters and basing films on the musical theatres. The tides eventually turned, and from the 1970s to the 2010s, it was Hollywood that became the inspiration for several Broadway shows, although films were still being based on Broadway musicals.

Recently, Hollywood has fallen in love with Broadway again. From the exceptional Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020), to the major hit Hamilton (2020), to the starry The Prom (2020), and the recent West Side Story (2021), Broadway is once again inspiring Hollywood movies in large numbers.

This relationship has, undoubtedly, been mutually beneficial, so much that during the COVID-19 pandemic, when theatres were closed and many theatre professionals out of work, theatre was somewhat kept alive in films adopted from stage plays, and a sizeable number of theatre professionals found jobs adapting stage plays to films. It is an enviable relationship, one that Nollywood and the Nigerian theatre have never quite been able to build.

Nigerian theatre dates back to prehistoric times, but it really began to take professional form in the early 1940s when Chief Hubert Ogunde popularised the travelling theatre, staging plays from one south-western town to the other.

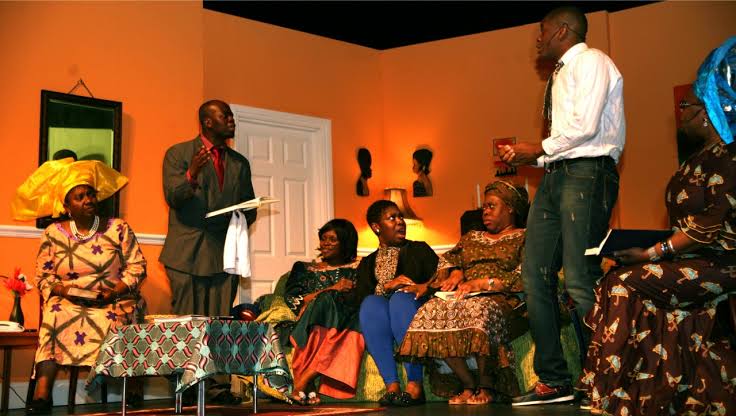

Nigerian theatre emerged as a variety of the Yoruba folk opera that combined what has been described as a brilliant sense of mime, colourful costumes, and traditional drumming, music and folklore, using Nigerian themes from modern day satire to historical tragedy.

Theatre soon grew to include literary drama, and notable playwrights like Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, Ola Rotimi, Duro Ladipo, and Oyin Adejobi, made invaluable impacts to the genre with their groundbreaking works. Between the 1940s and the 1980s, theatre in Nigeria (especially in Western Nigeria) boomed. Over forty years later, theatre seems to have lost its audience, and its continued existence seems uncertain. Most of its heyday audiences are no longer around, and it has struggled to win new ones.

Nollywood, itself, has gone through a rough patch. For decades, the industry has prioritised quantity over quality, and Nollywood has too frequently been ignored on the global scene. Nigerians commonly brag about their inability to watch Nigerian films, berating its quality and suggesting that people who watch them are of inferior intellect.

But since The Wedding Party (2016) grossed 453 million naira at the cinemas, and with recent Nigerian films like Eyimofe (This is My Desire) (2020) premiering at international festivals to critical acclaim, there is no denying that the industry has come a long way. Interest in Nigerian films has recently surged, both at home and abroad, so much that foreign film companies are seeking to jump on the Nollywood train.

With Nigerian films becoming more popular than ever, it would be very interesting to see theatre leverage on the film industry in re-establishing itself as a worthy vehicle for leisure and information. In a mutual relationship between Nollywood and the Nigerian theatre, like the relationship between Broadway and Hollywood, something profound is waiting to come out of both industries. So how can Nollywood help Nigerian theatre capture an audience?

The theatre could borrow some of Nollywood’s trade secrets. One of the most effective means of commercialising a brand is the use of famous faces. Nollywood has made a killing with this technique for decades. It has been noted by Barclays Foubiri Ayakoroma, PhD, that Nollywood, to a large extent, got its breakthrough because most of the actors who starred in Living in Bondage (1992/3), the first Nigerian blockbuster home video, were already popular on television for their appearances in many soap operas.

Even poorly made star-studded films do so much better at the box office and on Netflix charts than quality films with lesser known acts. The actors in the project often arouse curiosity from the audience better than the storyline, whatever it may be. Featuring famous acts in stage plays will ensure fans trooping to the theatre to watch their favourites perform live.

Between Richard Mofe Damijo, Rita Dominic and Adesua Etomi-Wellington, there are many Nollywood A-listers with backgrounds in theatre. In the process, the lesser known stage actors will get a chance to make their marks on the hearts of the members of the audience and become drivers of the industry, too.

Secondly, the importance of television as well as streaming and media platforms, especially in this brave new world of technology, cannot be overemphasised. Since the first television station was established in Western Nigeria, Nollywood has basked in the opportunities presented by the visual media. Even today, filmmakers and film companies are signing partnerships and deals to bring Nigerian films closer to both local and foreign audiences. It might appear at first look that adopting this technique may be detrimental to ticket sales. But that is not necessarily so.

When Dori Bernstein, a Broadway producer, aired a captured performance of her Broadway version of Hollywood’s Legally Blonde to MTV while the show was still active in theatres, there was that initial fear that its availability to be watched at home would be detrimental to the Broadway show.

But instead of sentencing the stage show to doom, it boosted ticket sales for the show, with viewers at home hungry to see the show live. It turned out to be a win-win situation. Even comedy shows that are aired live usually have full halls, and many who watch a previous edition from home pay to watch the following edition live. It stands to reason that theatre can benefit from this model as well.

Lastly, we have gleaned from experience that nostalgia and familiarity sell, even if using these tools is sometimes considered unoriginal or shameless by critics. It is nostalgia and familiarity that give remakes, reboots and present day sequels of decades-old films great commercial potentials, not just in the western world but in Nigeria, as well. It is the same reason churches, in the early days of Nigerian Christianity, reworked traditional songs, dances and drama into worship forms for the purpose of winning converts.

Nollywood can ride on this train of familiarity and nostalgia, as well as on the increased global interest in Nigerian content, and produce films that are based on or influenced by critically acclaimed Nigerian plays. A good place to begin is the effort already being made in this regard, with EbonyLife and Netflix’s film adaptation of Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman currently in the works.

Nigerians are familiar with plays being adapted to the screen. The very first feature film made by Nigerians and written by a Nigerian was Kongi’s Harvest (1970) also by Soyinka; and the television series adaptation of Ola Rotimi’s The Gods Are Not to Blame was the ninth season and one of the most popular on the anthology drama series, Super Story. These plays had earlier been performed on stage, to critical acclaim, before they were adapted for screen.

With Nollywood garnering more interest at the global stage, now is as good a time as any to bring back some of these classics and even adapt newer and fresher plays for screen. With fine execution and marketing, they can draw in both home-based and foreign audiences. And with a renewed interest in Nigeria’s literary art, audiences can more easily be wooed into attending the stage versions of the plays.

Theatre practitioners are encouraged to go the extra mile, like Broadway, by staging productions based on stories that were originally films. Filmmakers, in turn, can adapt popular stage plays to films. Between streaming services, international film festivals and performances on international stages, Nollywood and the Nigerian theatre can make important contributions to tourism.

Ultimately, not even Netflix-and-chill beats the feeling of watching a story that you have been sold on unfold around you. Lari Williams, writing for The Vanguard, put it this way: “[Those] who see the filmed version would be enticed to visit Nigeria to experience the splendour of the live version. Those who see the live version would be wooed into buying the filmed version for keeps.”

Of course, there are challenges to achieving this. But if it’s tempting enough, decent crowds will turn up as audiences for stage productions. After all, in 2013, Bolanle Austen-Peters’ Broadway-style production, “Saro the Musical,” had an audience of over 7,000. In 2014, the 11 shows of “Saro” were attended by 8,000 people over six days. In 2015, over 9,000 people saw 13 shows of “Saro” in six days. And less than five years ago, in 2017, “Saro” earned a standing ovation from a London audience with over 70 cast members performing on a unique Lagos-based custom-built stage. This was after Austen-Peters had put on a stunning show of “Wakaa! The Musical” in London the previous year.

It is true that with the consistently worsening economic conditions of the country, the terrible state of security, the absence or lack of government and even private sector funding, and the location of most of the very few arts and theatre centres in mostly upper-class environs — at least, in states where venues exist — bringing theatre to the average citizen is an uphill task. It is true that the problem with theatre is more than an audience problem. The cost implications are discouraging to theatre practitioners, and this is worsened by the fact that there are too few venues for theatrical performances, and even fewer with standard facilities.

Austen-Peters explained to The Guardian that “The majority of the cost [of production] goes into venue rental and technical cost since the venues are not equipped for Broadway-style Musical Theatre productions.” Yet, as Dr Ayakoroma insisted in a 2015 interview with The Nation, though insecurity and lack of funding have been named as challenges, “It is possible for us to cultivate our own theatre audience no matter the environment we find ourselves… If cinemas are thriving in this same insecurity environment, it means the ball is in our court. If we package good shows, people will come and watch.”

Everything boils down to packaging, he says. And he makes a good point. Despite the cost of living being more than double of what it was a decade ago, the average citizen still finds a way to visit clubs, cinemas and musical concert shows. If these are priorities; theatre, too, can be a priority.

However, productions must be excellent. It will not matter how much exposure theatre gets if productions are of a low quality. One thing is certain: If audiences show up to watch a stage play, for whatever reason, they will not stay if the show is not convincing enough for them to stay.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku, a film critic, writer and lawyer, currently writes from Uyo. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv and Instagram @_vivian.nneka