“Films from Namibia often go under the radar, and we struggle to attract the bigger platforms to showcase our work, but I think this is beginning to change” – Perivi Katjavivi

By Helena Olori

World cinema is seeing an all-time peak in diversity with storytelling as the era of monolithic narratives from Hollywood gradually fades. African filmmakers are increasingly illuminating the global stage with stories deeply rooted in their cultural origins, yet echo universal experiences. From the bustling streets of Lagos – which serves as the headquarters of Nollywood film productions – to South Africa’s industry and Kenya’s booming Riverwood, African film industries are replete with diverse stories that have put African cinema on the global map, gracing prestigious festivals, clinching coveted nominations and awards, and garnering critical acclaim from local and international critics. Yet, nestled beside a global competitor like South Africa, is Namibia’s film industry with only a handful of feature films — still finding its footing. Not very many of its films have achieved momentous milestones. The southern African nation, renowned for its scenic filming locations that have caught Hollywood’s eye, has been more of a backdrop in film production rather than a spotlight for its catalogue of home-grown content.

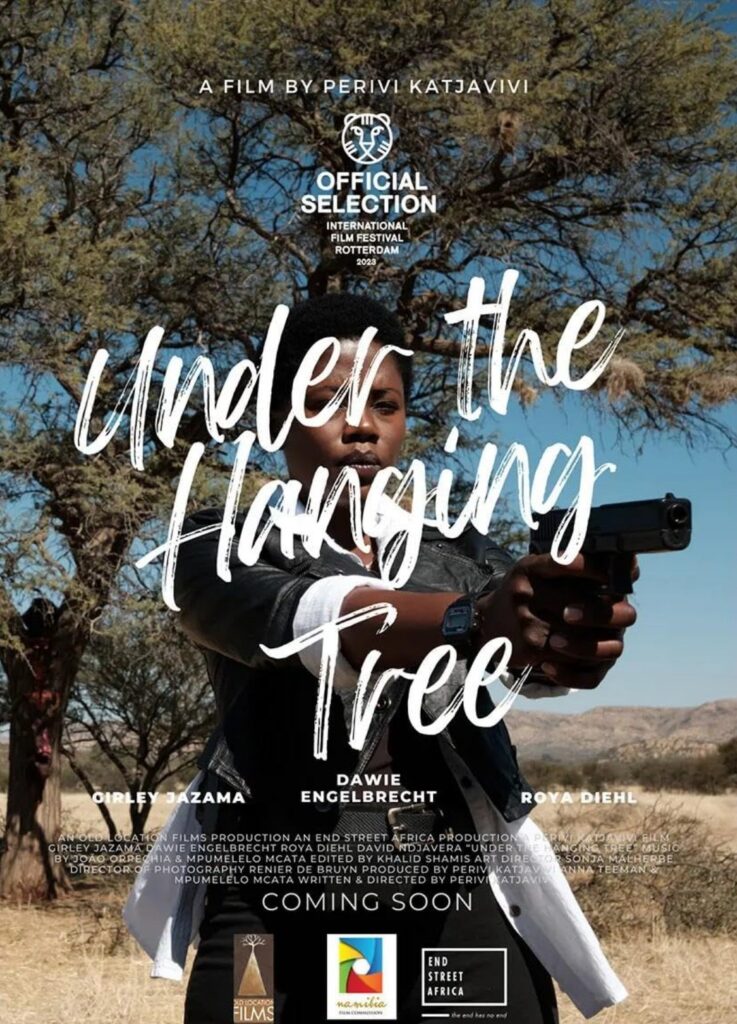

However, in a historic turn of events that signals a new era, Namibia’s International Feature Film Awards Selection Committee, on October 16, 2023, announced its nomination of Perivi John Katjavivi’s Under the Hanging Tree, as its first-ever official submission to represent the country at the 2024 Oscars. This ice-breaker moment, amidst cheers and applause, has turned the international film community’s gaze to Namibia’s budding film industry which, somewhat, has been overshadowed by its neighbouring Netflix powerhouse. The film joins other African titles vying for the 96th Academy Award for Best International Feature Film.

Under The Hanging Tree, written, directed and produced by the England-born-Namibian filmmaker, is a supernatural noir that explores Namibia’s dark colonial history, racism, and superstition, and has been praised for its creativity in telling a boundary-pushing narrative. Like his previous feature, The Unseen and Eembwiti, Katjavivi’s latest offering is centred on the cultural identity of his people and vividly captures the transgenerational trauma that trails the genocide suffered by the Herero people during the 20th-century genocide under German colonial rule. Before its groundbreaking entry to the Oscars, the film, starring Girley Jazama, Roya Diehl, and Dawie Engelbrecht, had its world premiere at the Rotterdam International Film Festival and toured several film festivals before premiering in Namibia cinemas on August 31, 2023, with much fanfare.

In the lead-up to the highly-anticipated Oscars shortlist announcement on December 21, 2023, the multitalented filmmaker shares with Afrocritik the inspiration behind his work, his multifaceted creative approach, its impact on local cinema, the honour of pioneering Namibia’s film industry to the global stage, and his aspirations for the future of the steadily-growing industry.

Congratulations on your film, Under the Hanging Tree being selected as Namibia’s official entry for the Oscars. Though, this builds on the success of your debut feature film, The Unseen, which received critical acclaim at various film festivals, how does it feel to be the pioneer filmmaker representing Namibia on a global stage like this?

I’m very honoured that our film has this special tag as Namibia’s first official entry into the Oscars. But it’s been made possible as well by many other filmmakers from Namibia who have laid the groundwork. I am touched that a film with these themes – history and the genocide – is being considered in this way at the highest levels.

Were you eyeing the Oscars when you set out to create this masterpiece?

It wasn’t the initial intention; it was quite a long journey to get to this point. I first started developing it as far back as 2017. But during the post-production phase last year, I began to consider the possibility of submitting it to the Oscars. And earlier this year, we ensured that we secured a cinema run to qualify for consideration at the Academy Awards.

As the first Namibian film at the Oscars, how do you see the impact of this recognition on the local film scene? Do you think this is a turning point for the Namibian film industry?

I do hope that it draws more attention to our little country and encourages other filmmakers to follow suit and submit their films in the future. Why can’t we have a Namibian film being considered every year?

Under the Hanging Tree vividly captures the transgenerational trauma of the Herero community. How were you able to depict such a sensitive and historically significant theme to resonate authentically with the audience?

That is because it is my story. I think as a Herero, as someone whose family went through this — my great-aunt was shot in the war and then went on to raise my father – these stories have been in my family and community for over a hundred years. But I do, at the same time, have some distance, through time and place, and this unique vantage, perhaps, helps. You want to be close but not too close.

The film adopts a contemporary approach with a noir style of storytelling in exploring colonialism, racism, and superstition in Namibia. What inspired you to combine these diverse themes in telling this story?

I love crime stories, noir, and Nordic noir. I began by watching television series and thinking, “Why can’t we transplant our heroine, our female police officer from the ice of Scandinavia to the desert of Namibia?” I think police officers are interesting within the context of these genres because they are usually flawed seekers of truth; investigating, searching for clues, digging up the past. This sort of character felt appropriate and well-positioned to be our avatar as we time travel back to colonial history and violence. I’m also a city kid – so to speak – so I was interested in a protagonist that is grounded in a city consciousness and must come to open up to their own culture, tradition, and ultimately, traumatic history, to solve the case.

What message do you hope these paranormal themes convey about Namibian culture?

I wanted to play with Herero mythology and mysticism a bit, and this is suggested in the use of fire, the names of some of the characters, the use of the sounds of dogs barking, and the use of proverbs as chapter headings. I wanted to work in the spirit of the “return to the source” genre in African filmmaking — that something pre-colonial and traditional is being suggested as the solution to contemporary African problems, in an updated premise that only through the individual’s personal gnosis and wrestling with their own “fire” or demons can we move forward. The narrative places power back into the hands of the individual, embodied by our protagonist, Police Officer Christina. In a time when focus often leans towards government or collective efforts to address the aftermath of violent colonial history, the film underscores the significance of individual agency.

(Read also: Four Nigerian Filmmakers, Actor, Receive Academy Awards Membership for 2023)

From Eembwiti to The Unseen and Under the Hanging Tree, your films are notable for addressing cultural identity, political themes, and the impact of colonialism in Namibia. How do you see your role as a filmmaker in shedding light on these issues, and what conversations do you hope to stimulate through your work?

I think chiefly because these are also my personal themes that I am interested in exploring. I’m ever curious about identity and history; about my creator, about humanity, and our psychology and idiosyncrasies. I sit on the edge of different film influences. I grew up watching Hollywood films but I gravitate towards techniques that can be found in slow or transcendental cinema. Reading Paul Shrader’s work (writer-director behind American Gigolo) had a huge impact on me. Discovering (French director) Robert Bresson, and (Thai filmmaker) Apichatpong Weerasethakul as well. It is mostly the privilege of doing my Masters of Arts in African Cinema that gave me time to study the greats and consider cinema as being more than just entertainment, art, or playing with time as some of the aforementioned influences might suggest, but as a cultural responsibility rather akin to the Griot tradition of West Africa. That is what stirs my soul the most so to speak. This kind of tradition and sense of responsibility of making sense of the pulse of things and being a wisdom keeper, of sorts. It is what happened to me during the process of making Under the Hanging Tree. There was an ancestral calling of some sort. That’s where I see my work shifting towards more and more in the future.

Would you say your family background – as a son of a Namibian politician and diplomat – influenced the themes or narratives you explore in your films?

I see in the many lineages in my family, both on the Namibian side as well as on the English side, a certain tradition — a long line of freedom fighters, politicians, artists, and religious leaders that fanned the flame each in their own unique ways according to the needs of the time.

As a filmmaker, your expertise extends beyond directing; you’ve also taken on roles such as producer, writer, camera operator, actor, cinematographer, and editor. How does wearing these different hats contribute to your overall approach to storytelling?

I must admit, this is not always intentional. The realities of indie filmmaking are that you often, particularly at the start, have to do much of it yourself. But I love the craft. I enjoy doing most of the things that come with making films — above and below the line. And I think it’s also the training I had when I was young, where you are forced to learn how to wrap cables and carry gear etc., long before you can play with a camera or direct or write something. It’s important to have an all-rounded understanding and ability about the craft.

With a background in African Cinema and your current pursuit of a PhD in Visual History, how do your academic leanings inform or add unique layers to your filmmaking?

The process — researching something and writing versus making a film — is the same for me. I go through the same creative process, and it’s like the detective archetype I mentioned exploring and unearthing. Regardless, I do think that one needs both a literal and research sequence eye as well as a creative lens to be able to grapple with whatever your subject or theme is. So, I’d like to think that the academic and the creative/practical both feed each other.

(Read also: Michael Omonua is Telling African Stories in the Language He Wants)

If you could pinpoint a pivotal moment that shaped your career as a filmmaker what would that be?

There have been many but I think my foundation; simply growing up in an environment where creativity and individualism were encouraged and getting to watch so many films, making films with friends and cousins as a kid. That ability to be able to play and explore without fear of what the outcome might be has always stuck with me.

In addition to your filmmaking, you also write for publications like Windhoek Observer, Africa is a Country, and OkayAfrica. How does your work in journalism and commentary intersect with your filmmaking, and do you see them influencing each other?

Sometimes, one may feel compelled to write an article, at other times, to make a film or pursue a longer field of inquiry like a research project, a book, or a degree. But I’d like to think it’s all the same work exploring identity, colonialism, history and the transcendent. Essentially, it is a search for a new language, a new methodology that allows all these efferent approaches to coexist more comfortably.

The film’s cinematography is praised, particularly its stunning depiction of the Namibian landscape. How do the visuals contribute to enhancing the storytelling and marketing of the country’s scenic filming locations?

Namibia is an amazing location for filmmakers. As seen in Mad Max – Fury Road (2015) and other big Hollywood productions, and in our film as well. The landscape is a character, and we wanted to highlight these vast empty open dry spaces that make up so much of the country. They’re beautiful but also brutal. It summarises our experience of Namibia aptly. The Director of Photography, Renier de Bruyn, did an incredible job at showcasing that. I wanted to juxtapose this with the 4:3 ratio to make the point that as much as you may want to get lost in the landscape vistas, this is more about humanity — the people. Hence the decision to use a ratio that is more suited for portraiture photography.

With the challenges of showcasing Namibian films (and most African films aside from big markets like South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya) outside the country due to streaming services’ disinterest in the small market, what alternative distribution models or partnerships do you think can explored to reach a wider audience?

I plan to just take the film around the country in an old Land Rover with a projector and a laptop. There are other ways like this that I’m able to take the film to the people. Most Namibians still live in rural areas so a cinema on wheels solution is one. The distribution challenges exist in the sense that films from Namibia often go under the radar and we struggle to attract the bigger platforms to showcase our work, but I think this is beginning to change.

We’ve seen the Namibian Film Commission funding projects annually – which is commendable – are there alternative sustainable funding models that can propel the long-term growth of the Namibian film industry?

It’s a small country, so unfortunately, there are still very few avenues for funding here in Namibia. We’d like to see greater support from the corporate and international film community. It is commendable what the film commission has achieved given the challenges.

Given the global recognition Under the Hanging Tree is bringing to the Namibian cinema, how can the industry leverage this exposure to attract more international investments and collaborations to boost the local film ecosystem?

I hope that they get on board at an earlier stage and ask themselves why they are not engaging with young Namibian filmmakers when they are in the process of developing and producing their films, as opposed to coming to the party after the film has been made.

Ahead of the Oscar’s nomination list which will be announced on December 21, what are your expectations and hopes for Under the Hanging Tree at the Oscars?

I think it’s a tall order to expect to make the list given how good the films are this year. But you never know, we have grappled with greater challenges just to get here.

If you dared to dream, where do you see the Namibian cinema in 5 years?

Winning an Oscar.

Helena Olori is a talented multimedia journalist; she enjoys staying abreast with latest happenings in the film industry and what makes the movie business tick. Connect with her on Instagram @heleena_olori or helena.olori@afrocritik.com