“We’re living through an era when civil liberties are being seriously threatened, and it is important for us to continue to tell stories of liberty, and of the bravery of ordinary individuals.”

By Helena Olori

I first chanced upon South African filmmaker, Ian Gabriel’s Death of a Whistleblower when the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) announced the line-up for its rebranded Contemporary World Cinema Centrepiece programme. As a lover of crime, mystery, action and political thrillers, the poignant storyline outlined in the synopsis, and Noxolo Dlamini’s command of the lead character as teased in the official trailer immediately captured my interest.

Death of a Whistleblower follows the story of investigative journalist, Luyanda Masinda, played by Dlamini, (Silverton Siege) as she seeks justice for her friend and fellow journalist, Stanley Galloway, who is killed for daring to release catastrophic state secrets. She teams up with whistleblower, Albert Loots (Irshaad Ally) to uncover a dangerous web of government secrets, double-dealing profiteers, and the deep-rooted corruption in South Africa’s military trade.

Though fictional, Death of a Whistleblower, in its 127 minutes-runtime, artistically mirrors the challenges faced by investigative journalists in South Africa and Africa as a whole, as it weaves together, in an authentic manner, threads of intricate past and present dark political realities in the region.

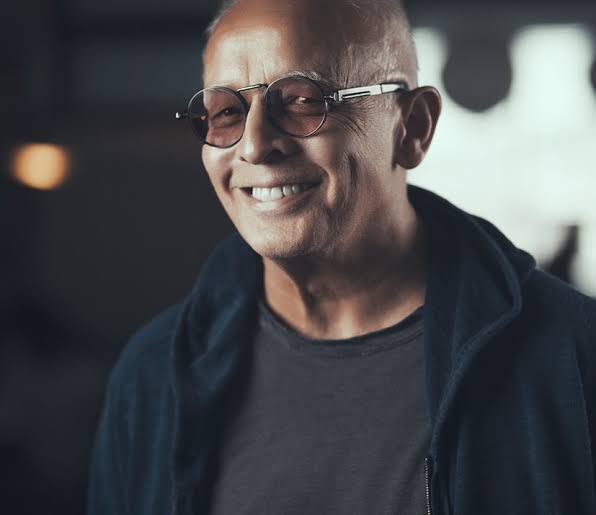

In this interview with Afrocritik, Gabriel, the first director of colour to start an independent production company in South Africa and three-time TIFF-screening director, shares insight into the creative process behind the Death of a Whistleblower, discussing the film’s real basis in South Africa’s historical context. He draws from his personal experiences during apartheid, while sharing his aspirations for bringing this age-old story to life. The ace filmmaker also speaks fondly of collaborating with his actor/writer son, Gabe Gabriel.

Note: This interview has been edited for length, style, and clarity.

Congratulations on the world premiere of your film, Death of a Whistleblower, at the Toronto International Film Festival. 35 years after the original idea was conceived, the film has finally premiered. How does it feel to see the project come to fruition?

It was very rewarding to have our film, Death of a Whistleblower, included in the Toronto International Film Festival Centrepiece official selection. Just to clarify, the film was not 35 years in the making. I mentioned that the opening scenes were scenes from a screenplay I developed in the mid-eighties, and these two scenes now play as a flashback introducing the audience to our film’s contemporary 2023 narrative.

This is not your first appearance at the festival. But as the saying goes, the third time is the charm. What would you say is significantly different about this year’s feature?

The audience reception at our screenings was very gratifying to witness. People were swept up by the drama and emotion of the film. For a filmmaker, I think each film one presents is like having one’s favourite children on display. You’re held responsible for the film’s strengths and weaknesses; you are in that parent position where you must continue to work to foster your film and guide it through its reception by the varied audiences the film confronts. Even interviews like this give us the opportunity to talk further about the trajectory of our film, but of course, to be strong, the film must talk for itself. Eventually, as a filmmaker, you stop carrying the film and hope the film will carry you a little through the challenges it faces, and hopefully, reveal new truths to you that you can build on for your next outing on film.

(Read also: Race to The Oscars 2024: A Look At The African Stories Vying for Best International Feature Film)

Death of a Whistleblower explores a compelling and complex subject – biological warfare in Africa and the Middle East. What drew you to this story?

For a start, I’m drawn to the film because it has a real basis in reality in that the South African biological and chemical warfare programme did exist, and this was revealed when I was still a young South African man hoping for a better South African future. If one examines carefully, there is a failure to make sure all the documentation and all the materials for chemical and biological weaponry are secured and accounted for. That is a disturbing truth that we continue to live with. I think we need to take account of its possible resurgence, and recognise that should the same horrors manifest again, they need to be more thoroughly and effectively dealt with than was the case in the early nineties when officials connected to the programme were still freely travelling about and supplying information to associates. There are unsolved and unrevealed aspects of this case that still fascinate me. I am also deeply aware of the power of the extortion economy that enables many of the misdeeds in South Africa – including the surge in the assassination of whistleblowers. These two powerful narratives provided us with fertile ground to till and develop our narrative.

(Read also: Beyond the Visual Aesthetics, Film Locations Are a Tool For Storytelling in Nollywood)

Your experience with the apartheid-era challenges in the 80s, as mentioned in the film’s backstory, must have influenced your approach to storytelling. How have your personal experiences shaped your perspective as a filmmaker, and are there echoes of those experiences in Death of a Whistleblower?

Yes, certainly. My experience of apartheid was central to my years growing up as a youth in South Africa, and evident in the varied experiences of the many branches of my very big and scattered family, many of whom were scattered by the processes of apartheid. Any story I tell, therefore, will always have echoes and reflections on the truths and challenges that my family and I faced during that time, first as a child, and then as an adult. My instinct as a filmmaker is to acknowledge the extraordinary courage and open-heartedness I always experienced from the many diverse South Africans, and how strong, courageous and deeply resourceful “ordinary people” are when faced with the unkind and brutal attitude that apartheid attempted to impose on all South Africans, whoever they were.

Your career has spanned diverse genres. How do you approach storytelling differently in projects, like the drama-comedy, Runs in the Family, compared to a crime series like Ludik or a thriller like Death of a Whistleblower?

Whatever genre I’m working with, I try to apply some sort of sense of truth that I’ve managed to cull from the events in my own life – the films I make are all about aspects of what I’ve seen and experienced. And yes, that does cross genres, as life does. So, I get as much of a kick out of playing with the facts of a family-based “dramedy” drawn from real events in my life as I do with a “franchisable” story about an investigative journalist like the hero Luyanda in Death of a Whistleblower. These stories have a way of becoming companions – as important as our friends and colleagues, and as one continues to move through and enjoy the diverse experiences of life.

Your collaboration with your son, Gabe Gabriel, on Runs in the Family must have been a unique experience. How did the father-son dynamic influence the creative process, and what did you enjoy most about working together?

It was a great privilege to work with my son in a director/actor/writer relationship. I think the flow of work and ideas between Gabe and myself has always been very open and spontaneous, and that’s why our work relationship flourishes as it does. Gabe and I are both inclined to experiment and look at new ways of doing things, so neither of us imposes any kind of lag or restraint on the other. We want to find out what we’re capable of creatively and that feeds our instincts as filmmakers. I think we’ll probably always collaborate from now on. It is special and I see no reason to not keep that “specialness” alive. It is a fresh and new resource that is going to keep me young, I suspect, for a very long time.

You also direct commercials and have worked with iconic figures like Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Cristiano Ronaldo, and many more. How would you describe working with well-known figures and directing newbies in the industry?

Well, the great thing about working with well-known figures is that you just walk straight into the reality of what they want to say. Nelson Mandela, in particular, was incredibly warm and receptive to us as filmmakers. When the AIDS crisis and its denialism were escalating dangerously in South Africa, Madiba (Mandela) was keen to deliver a very simple message – which was that he viewed the AIDS crisis as just as much of a threat to South African peace and prosperity as apartheid had been in a previous time. He didn’t have a lot of time allocated to us in his day, but he gave all of himself to us and to the country he was addressing, to let everyone know just how vital his message was. On the other hand, when I work with newbies as you say, I often have to try to get beyond initial restraint, to let the performers know that it is what they know that is important for us, that it is what we need to reflect on film. Not a false image, but a true one.

Let’s circle back to Death of a Whistleblower. How do you see the central thesis of the film – society repeating its errors without acknowledgement of the past – in relation to current global issues and struggles for justice?

I do think we’re living through an era when civil liberties are being seriously threatened and eroded by less and less tolerant ideologies and nationalisms that continue to rise as societies face ever-greater challenges. With that being the case, it is important for us to continue to tell stories of liberty and of the bravery of ordinary individuals – they are the ones who will save us from the potential folly of tyrannical leaders in the future, just as we have been saved in the past.

As a political thriller, Death of a Whistleblower connects past events, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with contemporary issues. How do you navigate the intersection of history and current social and political challenges in your work?

As a filmmaker, I look for signs of resourcefulness and redemption in whichever narrative I am working on. That is a choice I make at the outset – dealing with challenging political or social problems. My hope is that the curve of history and our own personal stories, whatever they are, will always lift upwards, towards something more positive in the future. I also think we are proceeding towards darker political realities, because our ability to be democratic is continually tempered by the systemically undemocratic aspects of unbridled capitalism that favours the “haves”, in unconscionable ways, over the “have-nots”. But the darker that reality presents itself, the more optimistic I am that there will be positive individual responses that display the better side of human nature, and reflect well on our desire to respect and work together in an equitable way. At the end of Death of a Whistleblower, there’s a track we use by Zakes Bantwini called “Osama”. It is a very positive uplifting track that gives a sense of the positive spirit of contemporary Africa. We chose it specifically to be the “leave the cinema track” for the audience, so they walk out having heard our message feeling positive and “ready to fight the good fight”.

The film has been described as a bulky story navigating South Africa’s past and present. What were some of the challenges encountered in bringing this age-long story to the screen, especially working with four screenwriters?

We always knew that Mandela managed to pull off a certain amount of positivity out of negative times and we as a country would have to spend time elaborating and improving on that positivity as some predictable roadblocks evolved further down the line. So, in part, that is what our story is about, and the challenge was to deal with our past and present with the same sense of urgency. Working with four screenwriters allowed us to absorb the varied instincts to coalesce our very South African story. I am pleased that we’re starting to develop a more focused South African narrative that tries to transcend the examples of the “foreigner as hero”, white man or woman as enabler, and colonial narratives that we’ve often had to stomach in the past as the only norm there was.

Noxolo Dlamini‘s spectacular performance as Luyanda Masinda is one of the most memorable parts of the film. What is your favourite thing about this project?

Undoubtedly, the work with the actors was where all the fun resided in this film. I wanted the audience to feel like they were “in the room” with the actors, experiencing the reality we were depicting. So, that was the code that I think we developed with the actors, they allowed us in on the intimacy of each of their relationships – whether it was the closeness between Luyanda and Astha (Kathleen Stephens) or Luyanda and Stanley, or the latent aggression between Luyanda and Mohale the Tracker (Anthony Oseyemi), or the latent alienation between Albert (Irshaad Ally) and the world around him – in informing the audience. That’s my favourite work in the film, but Dlamini was certainly a wonder to behold and to work with.

The film closes with a tribute to whistleblowers who faced violence in their pursuit of accountability. How do you envision the film contributing to conversations about transparency, justice, and the role of whistleblowers in today’s world?

Narrative filmmaking can be incredibly strong and convincing, and as filmmakers, we have the privilege of being able to reach a very wide audience. I think our film will reach a much wider audience, beyond the informed few who know about the plight of whistleblowers caught between corruption and the gangster state style of control and elimination that people like the late Babita Deokaran faced. So, I think this will contribute to the expansion and intensification of that conversation, and hopefully, with awareness comes a more circumspect and cautious pattern of behaviour in the future. It is our duty as citizens to speak out, to make the world a better place for our children.

You were the first director of colour to open an independent, director-owned production company in South Africa, and you have seen the industry evolve over the years. How would you describe the film industry now compared to your early years?

I opened the first director-driven film company back in 1979 when most film companies in South Africa were working, at least partially, with the SABC which everyone knew was a mouthpiece for apartheid in those days. What that meant then was that I needed to work exclusively in commercials because that and music videos were the only two areas of actual independence in South African filmmaking at the time. Fast forward to today, filmmakers now have the opportunity to work independently in all aspects of filmmaking. That is a big desirable improvement and there is more being done now to open up avenues for independent filmmaking across all the genres.

South Africa’s film industry is replete with crime/political thrillers which have contributed immensely in addressing socio-political issues. Are we expecting more thrillers from you soon?

I do like the thriller genre, but I think I will soon be drawn to some kind of cross-genre work, where we see maybe the thriller genre intersecting with something unexpected, maybe like music and comedy. You will have to wait and see.

Looking back at your career, from anti-apartheid theatre to international acclaim, what advice would you give to emerging African filmmakers facing challenges similar to those you have encountered?

I think as long as you stay focused on doing the work as it presents itself, there will always be opportunities out there, and there is an ever-growing audience who wants to hear what you have got cooking that is unique to you and your life.

Death of a Whistleblower is expected in cinemas soon, what should filmgoers expect?

It is a tense, exciting, and pacey investigation that also works as a franchisable story. So, expect to see a great gutsy performance from Dlamini. And expect more from us – and from her – soon!

Helena Olori is a talented multimedia journalist, she enjoys staying abreast with the latest happenings in the film industry and what makes the movie business tick. Connect with her on Instagram @heleena_olori or helena.olori@afrocritik.com