His idea of fame may have metamorphosed, but with his poetry, Chinua is charting new courses in the national memory of his troubled country…

By Chimezie Chika

As a child, Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto wanted to be an inventor. He dreamed of inventing something that would make his name known all over the world. He had read about the great inventors of the world: most notably Thomas Edison who invented the light bulb, and Graham Bell who invented the telephone. All around him, he saw these inventions and noticed how important they were to humanity. He decided that there was no better way to fame than becoming an inventor. For months, he was excited.

He dreamt of inventing things that would make the world marvel and long to meet him in person. At that point, he was watching many science programmes on television, and he saw that a lot of things had already been invented. Each item he conceived turned out to have been invented. He feared that this would derail his dream. Then, one day, he came up with a genius idea: a wristwatch with a television in it. He was giddy with excitement and went about telling everybody how he was going to become famous.

By his own account, he was a very creative child and had wild visions of the world he wanted. He first began expressing these precocious imaginations in drawing. Many of these drawings so impressed his mother that she kept some of them. With time, he grew dissatisfied with the drawings since they were not making him famous the way he wanted. He wanted to do something that would have an immediate impact in the real world, and so he had gradually stopped drawing and switched his attention to becoming an inventor.

To ensure that his idea of a special wristwatch was original, he told his well-travelled father to buy him a portable, handheld television on his next trip out. He didn’t know if such a thing existed, but he was testing the waters. If it hadn’t been invented, then he’d be the first to invent it. On his next trip, his father brought back two tiny devices that looked like transistor radios. These devices had antennae and received transmission that appeared on the tiny screens—one could practically tune in to television frequencies nearby and watch the programmes.

“I still have evidence of this,” Chinua tells me now. He goes into the room and returns to the sitting room with a tiny handheld TV. “It was one of those my Dad bought for me all those years ago. I don’t know why I still have it.” I examine the device. “You know, I was shattered by this discovery. It was the last straw. There was nothing I could invent that hadn’t been invented. At least that was what I thought in my mind. But that was the end of that dream for me.”

He focused on other things and lost interest in science as a career. One thing he did not lose, though, was the curiosity and penchant for all things imaginative, inventive and experiential.

*

Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto was born in 1992 in Awka where his father taught at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University. He recalls a happy childhood in which he had almost everything he needed. He read many picture books, and, influenced by their illustrations, started drawing.

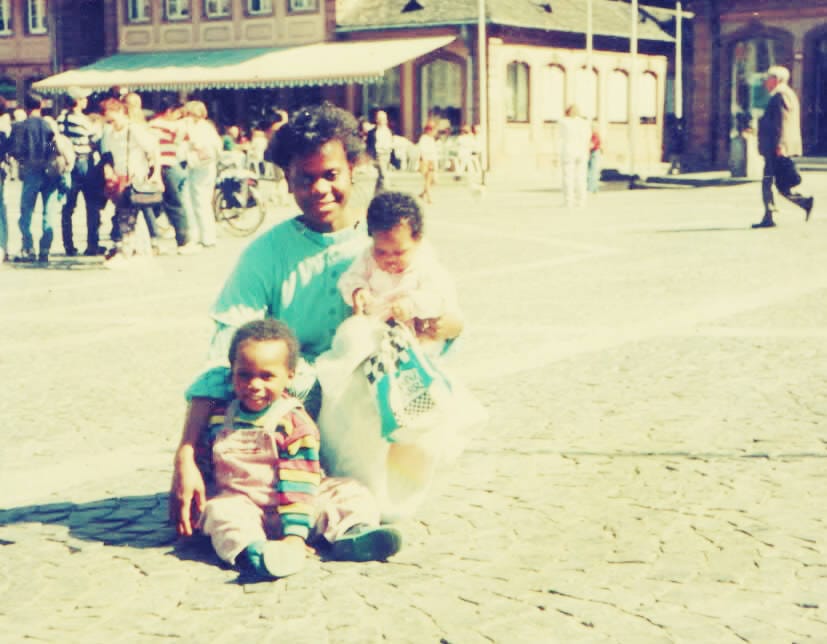

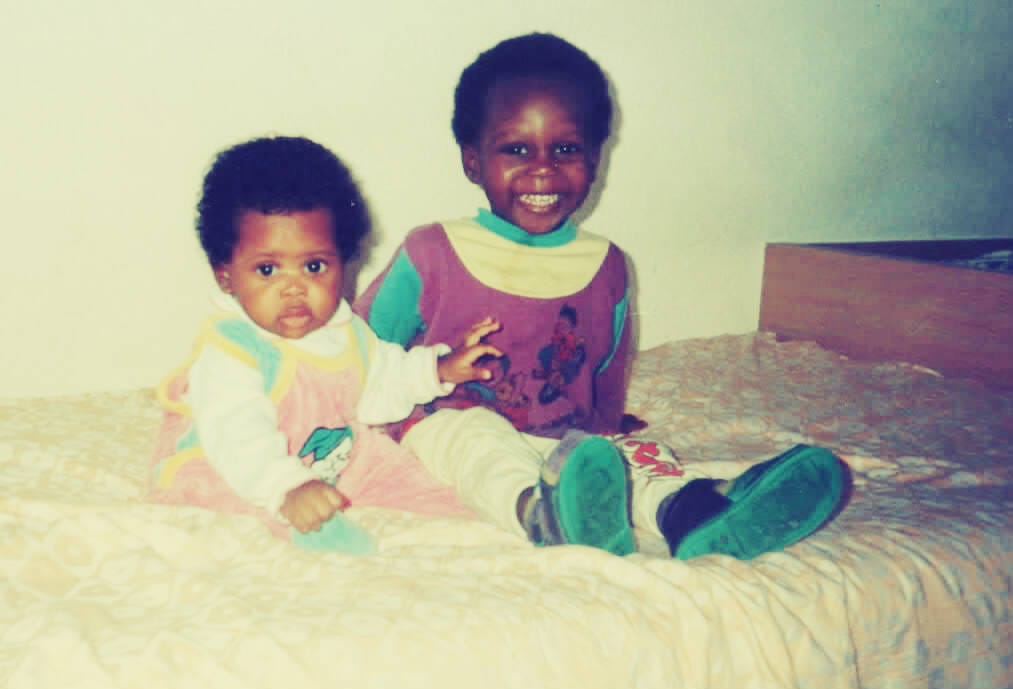

Chinua spent part of his childhood in Germany where, for a time, his father was a DAAD scholar at the University of Mainz. Some of his early memories are of a large apartment with patterned black-and-white tiles, wide roads and concrete kerbs. He recalls an incident in which he and his parents went to a beach and he poured sand on another child’s head. This incident remained blurry in his memory until years later his parents clarified it: the child he had poured the sand on was the son of a German couple who were also at the beach. The two couples had laughed over it, and that was the beginning of friendship between them.

Years later, in “A Handful of Memories,” Chinua would write: I hold the memory of my father/in my hand—this is how I grow chrysanthemums/for the scars I carried for all years. It is possible that Chinua’s excavation of the imagery of memory in his poems are a corollary of his own experience of memories. The lenses from which he sees these images inform how he may employ them. This is why further in the poem he entreats a higher entity: . . . put me in a corner/and trace the feelings garnered over the years.

The early desire Chinua had to invent and create things found tangible expression in its synchrony with memory. He recalls how he accidentally started writing poetry apropos of his father.

It began one sultry afternoon when he stumbled upon a book titled Voice of the Night Masquerade. He opened it and began to read words that ended in short lines only to begin in the next, the train of thoughts flowing, continuous and intermittent at will. For him, this was a new way of writing, and in it, Chinua saw the world spread out before him, supple and strange.

When Chinua finished the book, he wrote a poor imitation of what he just read and showed his father, who laughed, recognising that his son was only imitating his works, and afterwards, advised the young Chinua to only put down his feelings. This simple advice has since then been at the core of Chinua’s principle of writing poetry.

One thing that struck him, Chinua says, is that until he stumbled on that book which had his father’s name, “Ezenwa Ohaeto” engraved on it, he hadn’t realised that his father wrote books. This surprised him greatly. Perhaps, he reasoned, he did not know these things because his father travelled so much.

He hadn’t realised he had a father who was famous in academic and literary circles until his teenage years. He reasons that perhaps it helped that he did know about it as a child, that perhaps it helped his writing in ways he may not have entirely realised. And perhaps helped to develop his art free from his father’s shadows, to the point where he now writes a completely different poetry from his father’s.

*

Ezenwa Ohaeto, Chinua’s father, named him after his teacher, Chinua Achebe. For years, Ezenwa Ohaeto did prodigious amount of research on Achebe and finally published the only authorised biography of the writer titled Chinua Achebe: A Biography — a book that achieved instant success and quickly became a reference point on any discussion of Chinua Achebe’s life and work.

By all accounts, Ezenwa Ohaeto, who was a professor of literature at Nnamdi Azikiwe University, was an energetic man with a prodigious amount of academic and literary output. By the time of his death in 2005, he had published hundreds of academic articles, essays, over ten books, and won many awards including the prestigious NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature months before his eventual demise from cancer. He also left behind a mammoth amount of research for three or four manuscripts he was working on, including a biography of the Nigerian Nobel laureate, Wole Soyinka.

“I wonder how my father found the energy and time to produce so much in a relatively short time.” Chinua raises his hands in resignation. “I can’t do that. The world we live in now is very different. It simply can’t be done unless one can maintain the same level of energy. Then again, you have to have an understanding family, an understanding wife.” He recalls that his father travelled so much on different fellowships, residencies and visiting professorships. “You have to become a hermit of sorts to do that now,” he continues. “But I am not my father. We have very different trajectories when it comes to writing. He followed his own path, and now I am following mine.”

This is especially true of his poetry which is nothing like his father’s combination of political satire and cultural elements. Chinua’s poetry is more retrospective. His consciousness is that of memory and all its roiling accouterments. He reasons that he started taking poetry seriously in his senior year in secondary school. That was the year he finished his first collection of poetry. The next year, 2009, when he entered the Nnamdi Azikiwe University as a freshman, the Association of Nigerian Authors announced the ANA/Mazariyya Teen Poetry Prize for a poetry book or manuscript by a teenage poet. Chinua’s mother sent off her son’s manuscript to the prize, and months later, Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto was announced as the winner of the maiden edition of the prize.

“It surprised me even then,” Chinua says now of winning his first prize. “I hadn’t considered what a boon poetry could be. It opened my eyes.”

In his university days, Chinua performed his poems at different events. He was well known as a poet among fellow students and faculty. He wrote more poetry during this period. It seemed to him that his senses had become more acute so that he saw things through a certain convex. His feelings flowed on the page with aplomb. He drew his imageries from emotions springing from life itself; cosmic imageries, architectural and anatomical; imageries of weather, flora and fauna — ecological images that loop around topics bordering on war, family, love and loneliness.

He begins the poem, “In a City of Smoke I Found a Piece of a Half-Burnt Love Note,” this way:

I love you in a certain way, like a boy mauling his heartbeats into a school of butterflies. I love you in that certain way a dog bolts forward like a tractor in a cotton field.

Chinua’s choice of words illustrates his feelings. His poetry is also signatory to the peculiar and sometimes, atonal rhythm of words. Consider the picture of a boy cleaving his heartbeats, his life, with an axe, into pieces as many as thousands of butterflies searching for nectar. Consider a strong dog grinding and running after something many kilometers away. The journey becomes laborious at a point. If one puts love in the midst of these pictures, the picture becomes clear. How searing, how heartbreaking, the kind of complex emotions Chinua explores in his poetry.

*

Chinua began submitting his poetry to magazines in his late teens, around the time he started performing poetry in school. He talks about first getting published in the departmental journal of the English faculty of the university. He followed that with an acceptance into the ANA Review, the nationally-circulated journal of the Association of Nigerian Authors. He followed by submitting to international journals and magazines. He received many rejections but he soon learned to handle them well. He describes the first time he got into a journal based in the United States. He was full of joy. He felt that his work was making headway at last. It seemed that his boyish dream of being an inventor was manifesting in another guise.

In 2018, Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto won the Castello di Duino International Prize for his unpublished poem, “My Home: May Dawn Bring a New Smile Upon It.” It was his first major international award. He recalls the weeks leading to the award ceremony in Italy’s northern city of Trieste, his frantic struggle to secure his visa and air ticket, the anxiety of leaving Nigeria for the first time as an adult, and missing his first flight in the frenzy.

“I am grateful for the benevolence of late Prof. Gabriella Valera Gruber, who was the chairman of the prize board,” Chinua says now, lowering his voice a little, as though in veneration. “She graciously paid for my flight ticket again after I missed the first one.” Then he breaks the news to me of her having died of COVID-19 in 2020. Weighed down by the news, we sit in silence for a while as if in commemoration of all that the world lost during the pandemic.

Chinua arrived in Venice late in the evening in mid-March. His flight had made a transit stopover in Istanbul before arriving in Venice. Chinua then took a train to Trieste. In his often comic narration, he recalls how he nearly entered a train going back to Venice without knowing. Luckily, he had the presence of mind to ask an English-speaking stranger for proper directions.

His train arrived Trieste after 7pm in the evening, and he took a taxi to the Hotel James Joyce on Via del Cavazzeni, where the great Modernist writer lived for the better part of a decade, writing some of his major works while teaching at the Berlitz School. For Chinua, his arrival in one of Italy’s most literary cities was heralded by a biting cold. He recalls the welcome reading that evening, the classical music, the food, the guided tours around the city, the Sicilian meal they ate one afternoon, and the beautiful award ceremony where he received his trophy and the prize money of five hundred euros. He narrates visiting the seafront on the Gulf of Trieste. Walking on the pier, he was told of strong Bora winds that usually blew over North-Eastern Italy. These winds were so strong that they could throw one into the sea. Without waiting to hear the rest of the story, he ran back to the promenade.

“It was a beautiful experience. Being my first time, it was very important in my development as a poet.”

The same year, he won the New Hampshire Institute of Art Writing Award and was also scheduled to attend the school’s MFA programme. He would not go, however, for mostly financial reasons. He talks about his master’s degree at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University, and the bottlenecks he met while trying to complete the programme. “There’s a lot that is not okay in the country, from violent insurgency to ivory towers.”

At the time I interviewed Chinua, he was preparing for his Ph.D. programme at the University of Nebraska, where he will be in the same faculty as the two-time Booker shortlisted Nigerian novelist, Chigozie Obioma. He plans to further work on his manuscripts and start new projects. Moving is a constant in man’s life, and so he acknowledges how travelling and seeing new places and cultures will always present yet another opportunity to see life from a different lens.

*

Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto situates, crucially, memory at the meeting point of experience. He excavates personal and collective memory. An instance of national memory in his poetry is the title poem of his chapbook, The Teenager Who Became My Mother, in which he excavates violence as the memory of a woman caught in the middle of hostilities who was ”a graveyard to them/who drowned inside of her.” The poem’s depiction of the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria takes the form of a traumatic memory. The same thing can be seen in the poem “Home” in which he defines home as a paradox “where mothers are scared to birth.”

To read Chinua’s poetry is to be acutely aware of the senses, to see the environment around you with critical eyes, at once colourful and emotive. His poetry explores memories, violence, abandonment, trauma and borders. Sometimes it appears that all these are represented in one poem. This is true of the poem, “My Hands, Slender as Prayers, Fondle the Soft Rustle of Hope.” There’s also the poem, “The Things We Are Not Allowed to Raise,” where he explores the trauma of adulthood: “When I stand by people’s shadow, I/only want to dissolve and be/embraced.”

When I point out that there seems to have been a complete paradigm shift in the way poetry is written among Nigerian and African poets beginning from the mid-2010s, Chinua readily agrees but he does not provide easy answers.. He believes this could have a lot to do with the Internet as well as a kind of twisted interpretation of TS Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Whatever it was, he regards the change positively, for that was when many Nigerian poets began to win international awards with greater frequency.

Amidst all the melancholy of observation which poetry breeds, especially in a country like Nigeria with its violent upheavals, does the memory of his dreams persist? The permutation is that the dream still lives. His idea of fame may have metamorphosed, but with his poetry, Chinua is charting new courses in the national memory of his troubled country. And, in his poetry, we find what has become of that boy who harboured the dream of an inventor, reinventing his world in language.

Chimezie Chika’s works have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Lagos Review, Praxis Magazine, Brittle Paper and Aerodrome. A finalist for the Africa Book Club Short Reads Competition (2013), he was 2021 Fellow of the Ebedi International Writers’ Residency. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment.