… for all the dire consequences that result from the choices the brothers make in the course of the film, Amandla is not so much of a statement on consequences of one’s action as it is a statement on who actually suffers consequences…

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

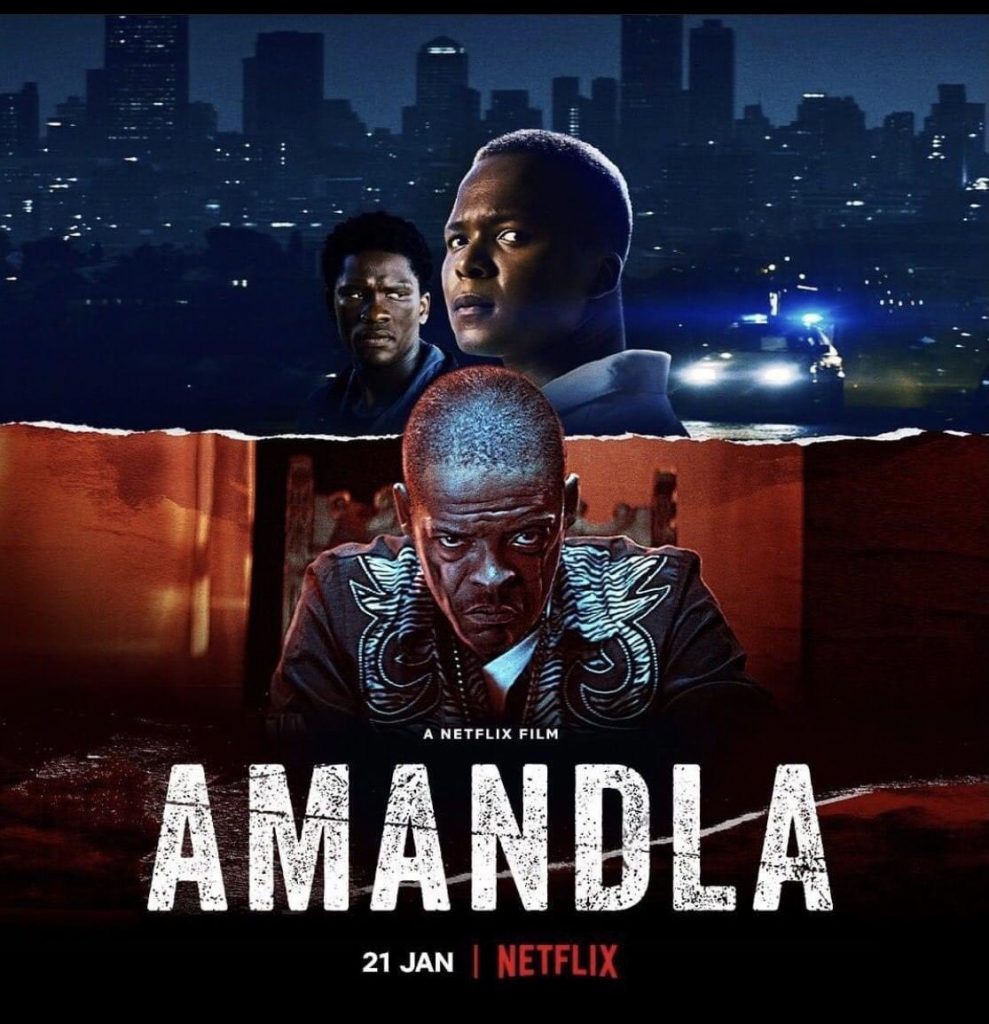

Two black South African brothers, Impi Khumalo (played by Thabiso Masote as a child and by Lemogang Tsipa as an adult) and Nkosana Khumalo (Bahle Mashinini as a child and Thabo Rametsi as an adult) are growing up on the Muller farm owned by a white family in apartheid South Africa. Nelson Mandela is still in prison, so we know that it is far from a joyful period for the segregated South Africans.

And with a statement here and a warning there from the Khumalo parents (Nqobile Sipamla and Ncibijana Madlala) to their sons, we don’t ever doubt that it isn’t a peaceful period, either. Yet, when the young brothers bond over bird hunting in those beautiful and serene fields captured so elegantly, and when they joke with “Miesies,” the madam of the Muller household (Natania Van Heerden) and her daughter, Elizabeth (Jeanique Fourie as a child and Liza Van Deventer as an adult), before going home to their happy, loving parents, it feels like pure, undiluted bliss.

But it doesn’t take long to sour, expectedly. The Khumalo family soon find themselves struck by a terrible tragedy that forces the brothers into a life of struggles and suffering. Then, we travel in time to follow the brothers as adults. Impi has had to become a criminal to give his brother whatever semblance of a good life the latter can get. And Nkosana, harbouring a guilt from their past, has decided to train to be a police officer as his way of helping restore justice to the country they both love. Expectedly, again, they “fall on opposing sides of the law,” as the Netflix description put it, “as a gang-linked crime tests their loyalty to one another.”

That is the story of Amandla, the South African crime drama film from Netflix’s stables, written by Nerina De Jager in her directorial debut.

By the time we transition to the brothers’ grown-up years in post-apartheid South Africa, Mandela has been president for more than three years — information that is very consciously passed to serve as confirmation that it is indeed post-apartheid era, but also to set the stage for the contrast between the past and the present. Too many years have gone by since their father tried to tell Impi that things had not changed. Since then, Impi and Nkosana have moved from one part of South Africa to another, with stark differences between the clean, serene wide spaces and the jam-packed bustling areas.

They have seen humanity at its worst, fueled by racism. Still, their faith in change remains unchanged. Nkosana is choosing the path of law enforcement because he still believes that he can make a difference. And Impi, with his many problems, believes that change has already come. Subtly but surely, the film mirrors that hope in a post-racism future that black people continue to nurse.

The word “amandla” means power, but De Jager’s film is less about power than it is about the lack of power. It is more about the circumstances that often serve as the backdrop for the “amandla” chant: the struggle for freedom. In this film, “amandla” is about the struggle of losing what is yours — your dignity, your home, the people and things that you love — and of being victimised in your own country because of the colour of your skin.

And for all the dire consequences that result from the choices the brothers make in the course of the film, Amandla is not so much of a statement on consequences of one’s action as it is a statement on who actually suffers consequences. And so, it is telling that throughout the film’s one hour and forty-six minutes running time, we watch multiple crimes unfold, most too heinous to go unpunished, but who actually pays for their own crimes or the crimes of others or both is often determined by skin colour.

Yet, there is something problematic about the fact that the one time a white person suffers the consequences of the actions of others, or of any action at all, it just has to be rape. For the longest time, western literature and television have employed rape as a readily available plot device in stories that centre men as heroes or villains. While the act of rape itself strips a female character of her agency, the film or literary work often strips her of the pain or trauma and, instead, doubles down on how it propels, affects or influences the men.

African cinema seems to be buying into this rape trope. In Amandla, it is wielded once again, this time, to establish a man as an unfortunate victim of circumstances.

Granted, this is a film about two brothers with a shared painful past. Even if it initially seemed to imply that it cared about little Elizabeth, it was never about any of the film’s women. And it didn’t have to be. So, it was never going to prioritise a woman over the men. But it definitely did not need to have any of its women characters raped, either. Without adding rape, there was already enough to justify how the film plays out and more than enough to situate the leading men as victims of terrible circumstances. A woman’s trauma does not need to be collateral damage in establishing a man’s victimhood.

Its reliance on the rape trope is one thing that speaks to its excessive eagerness to be tragic to a point of overkill. Another is its “What the f**k just happened?” conclusion. The overthinker in me could not help but think that maybe the film’s shocking ending was reasonable in a metaphorical sense. But to establish a metaphor using an illogical situation is still overkill. To avoid spoilers, it suffices to say that the film’s most shocking moments would be so impressive for unpredictability if they were not so unreasonable and unnecessary.

However, there was a lot of effort put into making this film. And a lot of heart put into the acting, too, especially on the part of both versions of the Khumalo brothers. The child actors, Masote and Mashinini, are their best when they’re just being brothers basking in youthful exuberance, and though they are not always able to carry the weight of the more serious bits, they are always interesting to watch. As for the older versions, Tsipa and Rametsi, they carry their weight with stronger shoulders and make it difficult to decide if you like them better when they’re just being brothers or when they’re dealing with the heavy stuff.

Undeniably, the screenplay could have been tighter. It’s surprising how people seem, too often, to know other people’s business and history, even though the film travels across very different parts of South Africa. The motives of the gang lord, Shaka (Israel Makoe), in compulsorily recruiting Impi are confusing, if not unclear. And the dialogue could have been better written to flow more naturally.

Still, Amandla is a sometimes compelling and mostly interesting crime drama that moves so fast that it never overstays its welcome. Maybe it would have been more effective if instead of wasting time on an unnecessary rape trope, it dug a little deeper into the life of crime Impi is said to have led and into the brothers’ relationship as adults. Unfortunately, that opportunity has been missed.

(Amandla is streaming on Netflix where it automatically plays the version of the film dubbed into English. Unless you want a frustrating experience listening to the English audio, switch to the original version before you watch this film.)

Rating: 5.7/10

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku, a film critic, writer and lawyer, currently writes from Uyo. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv and Instagram @_vivian.nneka

I was left thinking, what was the point of that film? Jampacked with cliches, unrealistic (is a white policeman really going to use the k-word in conversation with his black colleague in late 90s Joburg?) – I think the film’s only redeeming feature is that it clearly created employment for local people. South Africa is so full of incredible true stories, why make a fictional film this predictable? I knew what was going to happen in the final scene as soon as we’re told that the little brother is becoming a policeman.