Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s When We Were Fireflies is arguably the greatest novel to come out of Northern Nigeria so far, indeed a worthy addition to the pantheon of great Nigerian novels…

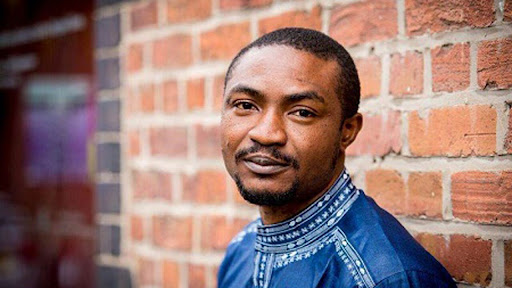

By Chimezie Chika

In his award-winning first novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim established himself as an important writer with the story of an unlikely love affair between a middle-aged woman and a well-known local rogue. His second novel, When We Were Fireflies, is also about love. But beyond that, it is the story of a man coming to terms with his multiple reappearances in different lifetimes.

In the story, Yarima Lalo, a quiet, self-absorbed artist, goes to witness the first train come into the Idu Station in Abuja. Upon seeing the train, a series of arcane memories he did not know he harboured comes back to him. Lalo remembers another lifetime, in which he is killed in a train. This singular memory becomes the catalyst for other memories and death from other lifetimes. In each of his deaths, he is killed for love. At the train station, he meets Aziza, who would, by her desire to understand Lalo’s mystique, force him to begin an investigation into his past, his old lovers, betrayers, and killers.

(Read also: The 2023 Caine Prize Shortlist Leaves Bright and Dull Lights)

This set piece which begins the novel is one of the most mysterious and gripping beginnings you will ever read in fiction. It is the premise that fuels Ibrahim’s accomplished tale of one man’s search for the meaning of life and death. Usually, we find that questions of life and death incur the most atavistic of all human emotions and actions: love, hate, and the violence that links them. Ibrahim’s Lalo is a fully realised character, stubborn in his repetition of love, empathetic in his dilemma, and conciliary in his own uncertainty.

There is of course a lot of mystery surrounding Lalo’s personality, for it is not normal that a man remembers memories beyond his present life. He etches these memories in his paintings. The details of his past come back to him in a systematic dream pattern. He wakes from his mnemonic dreams at exactly 2:14am each time. Each crucial event of his distant past, it is revealed, also happened at this time. In fact each of his deaths—or close encounters with death—occurs precisely at this time. His dreams reveal new details as he paints feverishly. Each colourful canvas becomes representative of the defining climaxes in his multiple lives.

Ibrahim’s use of magical realism is subtle. Each unusual occurrence seems normal. The ambiance that the writer creates around these events sanctions their rootedness in reality. Strange characters abound. There is Lalo’s mother, Kande, who sleeps for weeks on end. There is Libya, who sells fries on the street outside Lalo’s studio. Libya is a physically intimidating returnee from the ravaged North African country whose name he takes, but he also seems to be a counterpoint for lost things. The most recurrent of the novel’s set pieces is the ubiquitous presence of child fairies who collect fireflies in a cart. The curious story of these unworldly collectors are rooted in African mythology and the novel’s most dominant themes of life and death.

In its strange, encompassing way, the novel deals thoroughly with reincarnation. Abubakar seems to have asked himself the question: what if we are blessed (or perhaps cursed) to remember our past lives? What do we do with the overpowering onslaught of such new information? Will it make us better human beings or will it cheapen our vaunted existence on earth? What we learn in the novel is that, as human beings, there are many things we cannot control. But, of course, our vulnerability in the face of things we do not understand makes us human and strengthens our love and bond with one another.

Perhaps the biggest albatross man has encountered in his quest to create and innovate is death. It is the one thing we can neither understand nor change. In the novel, one of the child fairies that Lalo often encounters takes him to the roundabout where the fireflies that the child fairies collect are set free. Fireflies are the glowing souls of the departed who are no longer of this world, she explains to Lalo. Once a person dies, their souls turn into fireflies. The fairies collect them and congregate at the roundabout at night to set them free. The child informs Lalo that roundabouts are places where the fireflies make their final journey to the Afterlife. It is a startling imagery that explains our realisation that “of all the things in this world, the human soul is the most mesmerising of all.”

The image of roundabouts in the novel closely mirrors the belief in most African cultures that road junctions are liminal spaces or portals for the exchange of life and death. The Afterlife is itself part of the cyclical reincarnation of life. It never ends for human beings, Ibrahim seems to say, for we leave one life only to begin another. We were fireflies before we became humans and when we stop being humans, we become fireflies. We all have an unknown past lurking in the space between the living and the dead. Perhaps, with this knowledge, we become privy to a possibility that what we call death is just another lifetime. Lalo is a soul trapped in a loop of love, hate and death.

Ibrahim’s writing is observant, well-structured, and filled with glimpses of life in Nigeria’s north. A writer attentive to the spectacular and quotidian variations of life, Ibrahim has a deep understanding of the vagaries of the human condition. His clever plotting is evident everywhere in this complex narrative. His measured, lyrical style is replete with symbolism. Ibrahim knows his characters and treats them with consummate empathy. For the most part, the writing glitters with startling imagery: a series of roads in a roundabout are entwined “like a serpents’ mating ball”; a boy’s voice is “silken with innocence”; in former polo grounds which have been built up, Lalo sees “weeds of houses and people growing in the garden of his dreams.”

The reader will realise that the novel only gets better as it progresses. The early parts were leisurely and relaxed, but the novel picks up considerably when Lalo begins his quest into the cities and personages of his past. Thus the most enjoyable sequence in the novel begins with Lalo and Aziza’s visit to Kano to see Indo. Indo’s character is one of the most colourful, her words often punctuated with lurid curses.

(Read also: Emmanuel Iduma’s I am Still with You Contemplates War, Loss, and the Burden of Memory)

Lalo and his companions—Aziza and her daughter, Mina—encounter many things in the northern cities they traverse: Kano, Kafanchan, Kaduna, Jos. The histories of the volatile eruptions that have shaken Northern Nigeria through the decades—from the pogroms of 1966 to the contemporaneous Boko Haram insurgency—are intertwined with Lalo’s bloody past. There is something compelling about a young man, a young woman, and a little girl travelling in a car across Northern Nigeria’s sweeping vistas. In the travelling party, the young man is a man searching for vengeance across time, and finds only the crucibles of love that has endured for decades; the young woman is running away from the treachery of her in-laws while trying to feed her curiosity; the young child is playful and disinterested.

Lalo and Aziza’s love blossoms on this journey, a love often understated by the restraint and decorum of their culture. But it is evident where, in the absence of words, gestures and actions say more. The journey that these two embark upon is life-changing, no less for Aziza who will soon realise that it is difficult to return to the ordinary after an extraordinary experience.

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s When We Were Fireflies is arguably the greatest novel to come out of Northern Nigeria so far, indeed a worthy addition to the pantheon of great Nigerian novels. Its central concerns are searing and elemental, its characters are familiar, and the questions it raises are thought-provoking. This brilliant and rewarding novel is a humane story of one man’s search for meaning across time. Lalo would gradually realise that time is complex and ambivalent. “Time was a river, flowing, and lives were the water plants, flourishing and perishing with the tides.” In When We Were Fireflies, we see that the search for vengeance does not always end well; yet it is in the ability to forgive the failures of the past that we find redemption, such redemption as can be found in empathy and mutual understanding.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Republic, The Shallow Tales Review, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Efiko Magazine, Brittle Paper, and Afrocritik. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.