The work bears the twin markers of excellent prose and an intuitive sense of direction. Onyemelukwe-Onuobia leaves you with a satisfied, unsatisfied sigh…

By Joshua Chizoma

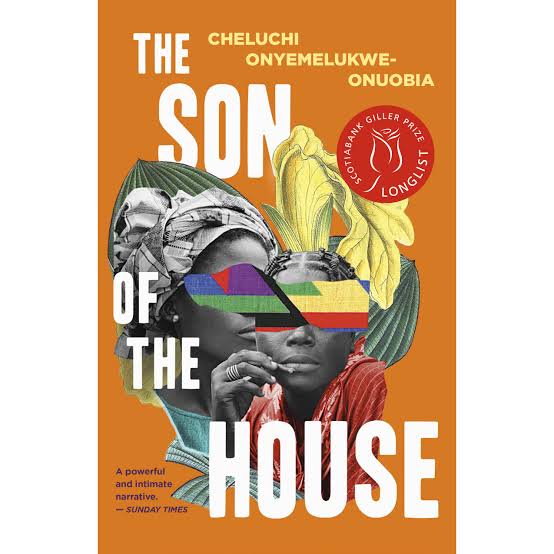

On the 31st of October, 2021, Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s debut novel, “The Son of the House,” won the Nigeria Liquified Natural Gas (NLNG)-sponsored Nigeria Prize for Literature 2021. The novel was published by Penguin Random House in 2019. The NLNG prize, which rotates between prose fiction, poetry, drama, and children’s literature, has been previously won by writers such as Jude Idada for “Boom Boom,” Soji Cole for “Embers,” Ikeogu Oke for “The Heresiad,” and Abubakar Adam Ibrahim for “Seasons of Crimson Blossoms.” The award, which paid homage to the novel genre this year, carries a monetary prize of $100,000, and is one of the richest literary prizes in the world. Joining “The Son of the House” on the shortlist were Obinna Udenwe’s “Colours of Hatred” and Abi Dare’s “The Girl with the Louding Voice.”

“The Son of the House” is a celebration of powerful storytelling. It tells of two women, Nwabulu and Julie who have varying lots in life but are bound inexplicably by fate. Nwabulu, on the one hand, is an orphan who is sent to Enugu to serve as a housemaid to a wealthy family. There, just when it seems her lot was looking up, she gets pregnant for a neighbour’s son. She is returned to her wicked stepmother, married off in bizarre circumstances, and then loses her child eventually. Back to square one, she runs off to the city where luck shines on her.

Julie, on the other hand, is the first daughter of a catechist and teacher. In her young adulthood, she gets her fair share of suitors, but keeps turning them away till she finds herself in her early thirties with no suitor in sight. She enters an affair with a married man, and eventually marries him. In a whirlwind of deceit, she connives with her friend to steal a baby to allay the problems in her marriage, buying herself three decades of bliss before she crosses paths with Nwabulu.

The novel is divided into three parts, with the two women taking one part each, and their voices merging in the last part, perhaps symbolic of the way their lives get entwined. Beginning in media res, Onyemelukwe-Onuobia sets the reader, blindfolded, into a quagmire. You stumble upon two women held in captivity, with no information yet about how they got into the situation. The author walks you through the process of untangling the knots, tracing a line to the beginning of the women’s stories and circling back to the scene in the kidnapper’s den before finishing up. This is a tricky technique that could leave the reader befuddled at the journey, but the book makes this transition elegantly and holds your gaze the entire time.

The story spans four decades, beginning from the late 1960s. Julie’s story, especially, begins soon after the Nigerian Civil war. Thus, “The Son of the House” joins such novels as “Under the Udala Trees” by Chinelo Okparanta, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun,” Festus Iyayi’s “The Last Duty,” and Chinua Achebe’s “There was a Country,” which are situated in the war period. The war and the political events act as a scaffolding, not the substance of the work. Stories about the war are usually about loss, about what the war took and is still taking, especially from the point of view of the Igbos who succumbed greater to the violence of the war. While many of such narratives explore the loss of possessions, “The Son of the House” tackles the loss of self. Onyemelukwe-Onuobia engages the psychological trauma Julie’s brother, Afam suffers as a veteran of the war. A light gets extinguished inside him, and he, who used to be a vibrant young man with scholarly ambitions, succumbs to drinking, eventually dying from a bar room brawl. The centering of the psychological effects of the war on the victims, as opposed to the questions of the loss of physical possessions. This is fairly uncharted territory as far as discourse about the war is concerned and is hence refreshing.

One other remarkable feature of the novel is its authenticity. The novel is set in the Igbo state of Enugu and refers to several other parts of ala Igbo, notably Aba and Owerri. Its cultural richness is also conveyed through evocative language. The novel is peppered with Igbo expressions, idioms, proverbs, and fables, which show that Onyemelukwe-Onuobia takes the Igbo storytelling tradition very seriously. Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s writing is sure and does not pander to Western idiosyncracies. The novel is obviously written for Nigerians, with Nigerian sentimentalities and sensibilities carried in language. Mrs. Obidiegwu, Nwabulu’s mistress, in chiding her, says, “None of these things walked in here by themselves. They were bought with money obtained with sweat.” You could almost imagine your “African mother” saying those exact words.

The novel takes on, amongst several others, the weighty subject of sexual abuse. Nwabulu is repeatedly raped in the first home she works as a housemaid in. Also, Ugonma, Urenna’s sister, is assaulted by her lesson teacher. Onyemelukwe-Onuobia, through Nwabulu, asks, “Did children ever get justice for such awfulness?” That is an interesting question that explores the state of the fight against sexual abuse in the country. And it is perhaps a subject the author, a professor of Law, is familiar with. Nwabulu is beaten by her aunt and accused of seducing the older man who raped her. Thankfully, with Urenna’s help, justice is gotten for Ugonma. This turn of events is wonderful because in most real-life cases, victims rarely get justice.

But the novel suffers from the problem of clinging to clichés. Nwabulu’s story is not exactly peculiar. In fact, it is not peculiar at all. The trope of the young orphan girl besieged by misfortune, who serves as a maid and eventually stumbles upon fortune, is replete in literature. Admittedly, the author tries to temper its “clicheness.” Thus, for instance, Nwabulu is not a sweet innocent girl. She carries on a sexual affair with Urenna. Her benefactors are likewise imperfect. Mr. Obidiegwu is fastidious to the point of being exasperating, and his wife, spineless, panders to him, lashing out at Nwabulu all the time.

True, the novel tries, but it isn’t very successful, especially as it drops the ball again in its resolution. Nwabulu eventually dusts herself up, gets very successful in life to the point of making clothes for celebrities, and even eventually meets her son taken from her years before. This story begs the question: aren’t grass-to-grace stories outdated? Are we not done with them now? There is the allure of creating an imaginary world where good triumphs, but it hampers believability. This was the chief complaint against Hanya Yanagihara’s Booker Prize-nominated book, “A Little Life”: the portrayal of a utopian world where everything is bright and sunny, a kind of world no realistic novel should be set in.

Then there was the danger of explaining too much, of moving backward. This is especially the problem with the third part of the novel. It lags in some places, going in circles when it should be shooting off. For instance, in chapter fifteen, when the reader ought to be introduced to Julie’s deceit, the reader deals with a seemingly needless commentary about Obiageli, Julie’s friend’s, marriage. Then in chapter nineteen, Julie goes through another needless bout of introspection, and we learn about Mmaku, Eugene’s mistress.

That sub-plot literally had zero impact on the novel. Because if it sought to establish that Julie was ruthless, the reader already knows that at that point in the book.

Again, there is the question of the plot of the story. It is exaggerated in some places and implausible in others. So, Julie deceives everyone that she is pregnant, up till the fifth month, and also claims to have lost the baby, yet no one notices or suspects the deceit. Even more fantastically, she steals a baby with the connivance of her friend, goes to the UK, comes back, and claims it to be hers. Twice deceitful, still no alarm bells ring. Understandably, the deceit was easy to perpetrate because of Eugene’s desperation for a child. He saw what he wanted to see, believed what he wanted to believe, and made everyone shut up. Still, still.

There is the obvious question of Obiageli’s husband, who must have known about the child since the child was in his house for months. He surely could have recognised the boy when Julie brought him back from the UK. There’s nothing about how he handled this.

In all, the story is brilliant because of its themes and the power of its prose. The language is dreamy and reads like a tale from the mouth of a powerful storyteller.

“The Son of the House” is about Julie and Nwabulu, and at the same time isn’t. It is about the men in their lives, whose accident of birth made them sons of the house, placing them strategically above the women. The shadow of the men falls over the novel’s women, is the unseen hand that steers their boats, dictating where their lives went. This is why, even though Julie has sisters and another brother, it is forgivable that the story focuses just on her relationship with her brother, Afam. It is the death of Afam that pushes her to marry a man in search of a child, a man she ensnares with a pregnancy, the promise of a male child. It is in her search of a son for the house that she steals a boy and foists on her husband. The primacy given to male children is also the reason Nwabulu marries “a dead man” so she could birth a son of the house for his mother. Today, several years away from the 1970s, it is remarkable that things aren’t so changed. Because without the stamped timeline, the story may well have happened in today’s Nigeria.

Their story, as we see, is not unfamiliar. It is an excellent treatise on the prejudices and the weight of societal expectations on women. It shows that a woman, whether wealthy, affluent, or not, gets the short end of the stick, always. However, the women survive, nay flourish, in spite of the men. So, Obiageli, Julie’s friend, survives despite her husband’s miserliness. Julie survives her husband’s extramarital affairs. Mrs. Obidiegwu eventually separates from her husband, and Nwabulu survives Urenna’s betrayal.

The novel’s ending is fascinating. Once you deal with the women’s individual stories and get back to the kidnapper’s den, you are almost forced to ask: now what? Onyemelukwe-Onuobia does not leave you hanging. When the author sets the reader down from the peak of the novel, everything makes sense, even the shackles Julie and Nwabulu are bound with in the den, because are they not both joined in the hip, the mothers of the same son? The resolution is beautiful to watch and raises several questions in your mind. Nwabulu forgave too easily. How did they become friends after such a revelation? Why is Nwabulu sad when Julie falls into a coma? However, this is a satisfactory kind of pondering. The author leaves you on a path where you can navigate your own ending, find your way to the end of the story you want.

The work bears the twin markers of excellent prose and an intuitive sense of direction. Onyemelukwe-Onuobia leaves you with a satisfied, unsatisfied sigh, a longing for a little more, just like all good stories do.

Joshua Chizoma is the winner of the 2020 Awele Creative Trust Short Story Prize and a finalist for the 2021 Afritondo Short Story Prize. He writes from Enugu, Nigeria.