Daring, ambitious, visually stunning and appropriately heart-wrenching, The Milkmaid is a cautious exposé on the experiences of women in the midst of violent conflicts, and the effects of extremism on women and girls…

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

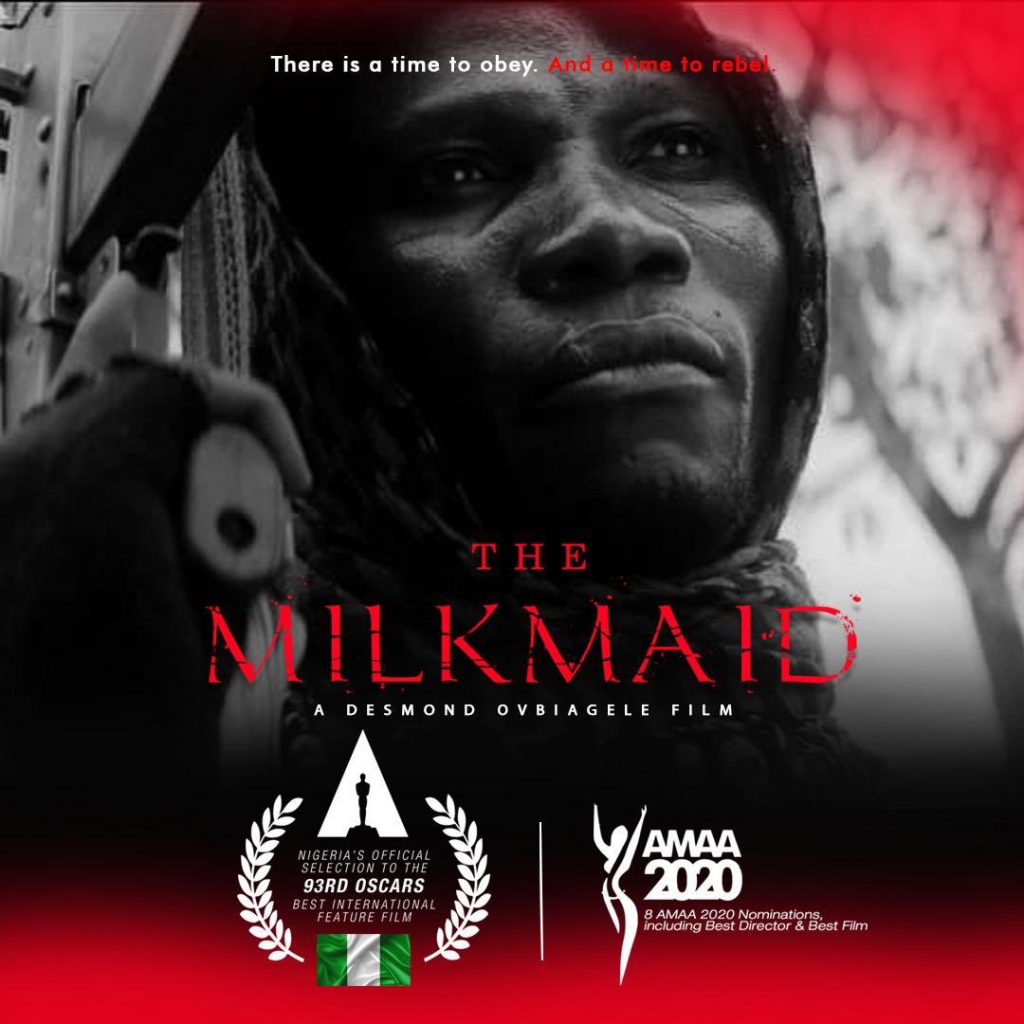

Nigeria’s first submission for the international film category at the Oscars — after Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart was rejected the previous year for being ineligible — Desmond Ovbiagele’s The Milkmaid was the remarkable terrorism-themed feature that made waves at the AMAAs in 2020. Unfortunately, the film was heavily censored by the Nigerian Film and Video Censor Board, and got its theatrical release in Cameroon and Zimbabwe instead. It only played in select Nigerian cinemas after a chunk of footage had been cut, leaving Nigerians at home with both a limited and incomplete viewing experience. Well, thank goodness for streaming platforms! We can all now experience the fine piece of cinema that The Milkmaid is, albeit on the small screen.

The Milkmaid is set in an unspecified rural part of Sub-Saharan Africa where a violent conflict rages, helmed by an unnamed Islamist extremist sect. It follows Aisha (Anthonieta Kalunta), a young Fulani milkmaid, as she and a younger girl, Hauwa (Patience Okpala), struggle to survive the harsh world all on their own, and as Aisha risks everything in search of her younger sister, Zainab (Maryam Booth).The three of them are abducted by the insurgents, alongside other girls and women, during an attack on their village on the day of Zainab’s wedding. They are taken to the insurgents’ camp where they are mistreated and forced to do hard labour and observe compulsory fasts. Before long, the sisters are forced into marriage with insurgents, Aisha to Dangana (Gambo Usman Kona who doubles as the film’s location manager), and Zainab to Shehu (Alex Pwatildi). A fighter, even as a victim, Aisha takes the first chance she gets to escape. But she gets separated from her sister, leaving only with Hauwa. She then decides to go back for Zainab, returning to the oppressors she escaped from and discovering allies and traitors in the people she least expects.

Inspired both by the two Fulani milkmaids pictured at the back of the ten naira note, and by the present-day reign of terror being perpetrated by the Boko Haram terrorist group, particularly the Chibok school girls kidnapping, The Milkmaid confidently delves into the horrors faced by female victims of violent extremism. As much as possible, Ovbiagele avoids showing the violence in graphic detail, but it’s still a harrowing exposition as we watch the insurgents upturn the girls’ simple but happy lives as milkmaids. The film explores the many facets of pain that they go through, from not knowing whether their loved ones are alive, to being forced to marry their oppressors, and being rejected by their families because of the uninvited changes to their lives, even when they somehow make it back home. In The Milkmaid, women remain at the forefront of the story as they work through their undeserved shame and suffering, and even when they find ways to take back the power over their own lives.

However, Ovbiagele goes even further, attempting to dissect the mindsets of the violent extremists themselves. The film humanises them, but it doesn’t justify their actions in any way. In fact, it points out hypocrisies in their methods. It’s interesting to see how the insurgents justify their choices, even when it comes to matters of their own faith. When they force a husband on an already-married Aisha, they absolve themselves of any sin on the ground that she cannot bring proof of her marriage, even though they are the ones keeping her captive. When Hauwa complains that she’s not old enough to be married, one of the insurgents makes the point that his own 5-year-old daughter is married. And in one striking monologue rendered offscreen, a woman pitches suicide-bombing to another, using feminist ideologies. “The men rule everything,” she says, “although we are not less intelligent than they… Does that seem fair to you? It is not. And we know that God is just, so it stands to reason that our roles as women cannot be only to cry and keep the household in the absence of men. No, we are to be full participants in the fight. We are just as capable as they, if not more.”

Daring, ambitious, visually stunning and appropriately heart-wrenching, The Milkmaid is a cautious exposé on the experiences of women in the midst of violent conflicts, and the effects of extremism on women and girls. It is very specific about its Sub-Saharan setting, even though Boko Haram is never expressly mentioned in the film, and just before the credits, the film makes sure to honour the memory of real-life victims of the Boko Haram insurgency. Yet, there’s a global appeal to it, since millions of women and girls in conflict-ridden areas across the world share similar agonising experiences. Plus, although no explicit political connections are made, the film makes accusations that are simultaneously bold and subtle — from hinting that the insurgents have informants within the country’s security forces, to making a case that the hideouts of the insurgents are not really hidden.

Eventually, although The Milkmaid won Best Film at the AMAAs, and had a good run at the festival circuit, it did not get nominated for the Oscars. Still, it’s an impressive feat for Ovbiagele whose second time it is directing a feature film. Ovbiagele’s debut was 2014’s Render to Caesar which premiered to mixed reviews. He wears both the writing and directing hats, even though he doesn’t speak Hausa, Fulfulde or Arabic, the predominant languages of dialogue in The Milkmaid. His screenplay in the film isn’t the smoothest it could have been, and the way it moves back and forth between the past and present makes the timeline difficult to follow. But his approach also keeps the otherwise slow plot eventful for most of its running time of two hours and sixteen minutes.

Good for him, his crew includes very skilled Nollywood hands. Yinka Edward’s (Lionheart, October 1) cinematography brilliantly situates the characters in the film’s various imposing environments without ever losing focus on the people. The score, composed by Michael “Truth” Ogunlade (The Wedding Party, Sylvia) is effective in stirring up emotions. The costumes by Obijie Oru (October 1, Coming from Insanity), the makeup by Rahila Manga, and the production design handled by Pat Nebo (‘76, October 1) are all just stunning. The film does not always have the best acting, but it’s not particularly weak, either. Kalunta and Booth render convincing performances, the former with an almost laidback but fierce portrayal of Aisha, and the latter with a solid transformation from the formerly helpless Zainab to the ruthless Fathiyya. Kona more or less steals the show, with a nuanced depiction of a truly complicated man — one who can love his wife but can also commit violence on her, and a religious person torn between moderation and extremism.

Altogether, this is some good filmmaking. There’s more work to be done, but this is a wonderful addition to Nollywood’s terrorism-themed cinema and, frankly, the entire industry. A new bar has been set, and it’s high.

Rating: 4/5

(The Milkmaid premiered in 2020 and is now streaming on Prime Video here).

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku, a film critic, writer and lawyer, writes from Lagos. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv and Instagram @_vivian.nneka