By Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera

I am seated at Chuckies Restaurant in Nnamdi Azikiwe University with writer Obumneme Osuchukwu, Afro-Soul singer Somtochukwu, and Daniella, a spoken word artist. It’s not long before Gerald Eze, a music lecturer, comes to join us. Eze is spotting a combed Afro and an untrimmed beard. He is holding a collection of the Ọja, the Igbo talking flute. Our sitting position is such that we are seated opposite each other, two on one side and three on the other, to ease our conversations. We are inside the university today to talk about a plan that I and Osuchukwu had conceived nearly two months ago: to begin a movement of young people who are enthusiastic about the use of art to spark a national renaissance.

Earlier that day, we had met at Eze’s office, located in the university’s Faculty of Arts. There, he regaled us with stories of his dissatisfaction with the way colonialism had led us to refer to western music composition from earlier centuries as “classical music”, while (dismissively) referring to Igbo music from previous generations as “traditional music”.

Eze joins our discussion at the restaurant, visibly excited, obviously having a lot to say. He begins by saying, “in our society, so many things have lost their relevance because people do not realize the powers that these things possess.”

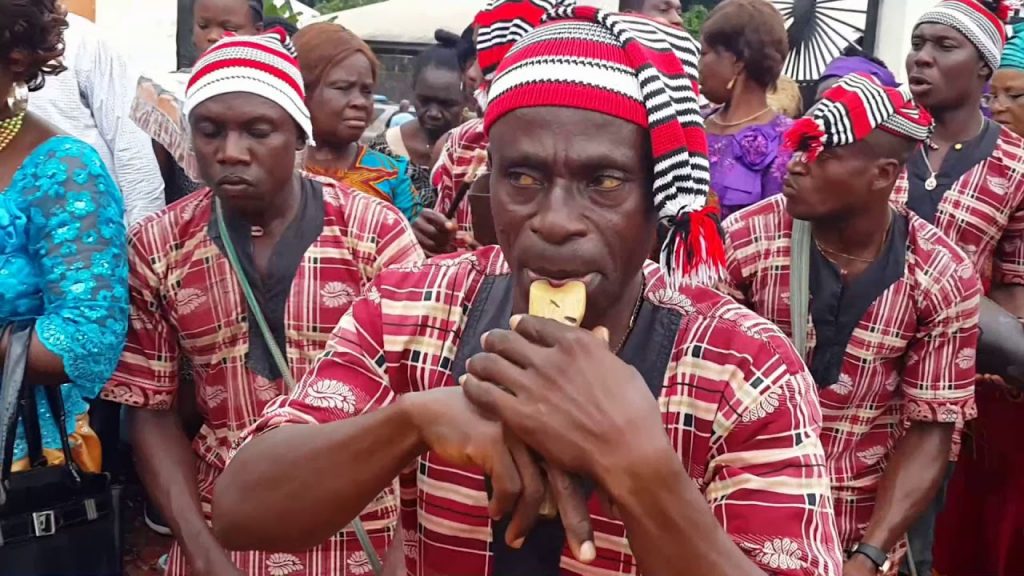

After listing a litany of things that bother him, he lifts the Ọja which he is holding and says, “even the Ọja these days is being used to beg for money…”

He pauses to allow the disappointment to settle on our faces and he continues, “because they do not know the spirituality of what they have in their hands.”

He talks extensively about how the Ọja speaks to everyone who listens deeply to it, and how a good player of the Ọja did not need to beg for money, but could move people to dip hands in their pockets with the quality of his playing. Then he picks the Ọja from the table, raises it to his lips, and begins to play it, immediately enchanting the restaurant. For a few minutes, everyone draws closer to where we are seated.

After playing for a while, he puts down the Ọja and says, “Do you know that the Ọja can call you by the name? If you listen well, you will hear it calling you.”

He picks it again and begins to play a different note. I close my eyes and I try to imagine it calling my name. Not having enough exposure to the music of the Ọja, I can’t say I succeed at this. But I have felt enough to know that I am almost always tempted to rise from my seat every time music flows from the Ọja.

According to Eze, the ability of the Ọja to communicate with a person is deeply tied to spirituality since the music does not involve the use of words, just the same way two people deeply connected can communicate through their silence. He would play the Ọja, pause, talk about its different virtues, and play some more.

On the individuality that the instrument exudes, he says, “no two people ever play the Ọja in the same way. Even if there are hundred people here playing the Ọja, each sound emitted will be unique in itself.”

From this perspective, the Ọja exemplifies the individuality which is espoused by Igbo philosophy.

After Eze plays for another 30 minutes, a young dark-complexioned man comes over to our table, visibly excited. He asks who the Ọja player is, and we point to Eze. The young man says, “Bros wetin you dey drink?! I want to buy you beer! How many you fit drink?!”

The young man buys three bottles of Heineken for Eze and buys food for me and Somto. We were in the pub getting goodwill from a man willing to buy us drinks and food, and asking us what he could do to see more of us and our music, without us having to solicit for any of that.

“I live in Lagos”, he tells us, “I for like make you come play this thing for us. Wetin you dey drink? I go ball you.”

The Igbos have this fable about a great wrestler called Ọja Adili, who after beating every wrestler known in the land, led by the music of the Ọja, headed into the land of the spirits and successfully wrestled with some of the finest wrestlers in the land of the spirits. He refused to go home and boasted that he wanted the best wrestler. The spirits came together, deliberated on how to stop Oja Adili, and sent him his chi, a wiry erratic spirit who lifted him up with one hand and flung him on stony earth.

The above fable is often deployed in instructing a man never to challenge his chi, but the ancestors also drew out a lesson about the Oja from the story: the Oja is so enchanting, and its spirit intoxicating, that it can lead men to perform great exploits, and at the same time it can lead a man to his destruction. This is what the Igbo mean when they say “Oja a dufuo dike” (the Oja leads a strong man astray).

This powerful instrument is so hypnotic that it leads men to part with their money. A good Oja player need not beg for money before he is serenaded with it. It is probably the reason why, in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Unoka, Okonkwo’s father, had more people loaning him money in spite of the fact that he was a chronic debtor.

There are not enough people learning to play the Oja these days. According to Eze, people who beg for money with it are amateurs who don’t know how to play more than two notes. This is why he goes around preaching the gospel of Oja, carrying a collection of the instrument wherever where he goes, selling it to those who want to either own it or learn how to play it.

The following day, we gather at his apartment. We are surrounded by different musical instruments in his sitting room. He tells us he is a good listener of music and listens to all forms of music, even rap. But he is not as drawn to lyrics as he is drawn to sound.

“It is sound that has taught me the art of listening. Since the colonial era, we Africans have been talking about how to stage a revolution. We talk about reading books and all that. It’s good, but we need to infuse theatre and music too. We need to amplify the sound which draws us back to our roots. Books and knowledge can start conversations, but it is sound that will bring about the revolution, and that is why we should take our indigenous sounds more seriously.”

Through Eze’s eyes – and lips, and hands – we come to see the virtues of the Oja from a philosophical standpoint. We learn of its spirituality and ability to communicate. As a teacher, he teaches of the importance of sound to the forthcoming renaissance. The kind of sound listened to by the previous generations of a lineage always has a spiritual connection with those who live in the present, because it comes like a melody travelling through a time machine. This is perhaps why the Oja is so enchanting.

I absolutely love this piece. Never thought of the Oja this way. Good job Michael. Thank you for this piece.

I’m glad to be able to recognise the oja, a very significant classical instrument of my igbo tribe

Even without having prior knowledge of the music instrument, the writer draws you in with his storytelling, and effortlessly explains why culture is important. This was an amazing piece, Michael. Good job.

Great piece, Michael. The Oja is indeed a powerful instrument.

I enjoy the piece to the point that Eze’s interest is very much pregnant of the oja.., and, I look forward to follow up on it. Nice job, Michael.

It is sometimes described as the Oil with which Igbo music is eaten. The sound energizes the weak and calls up the very aged to jump up in strength as they dance to its calls. Performers: Bartholomew Ogbu ike anyi ji eje mba , Charles Chukwudozie, Chinyelum Ewelum.