Although the films screened at IIFF are of varying degrees of success and failure, each film will eventually find its audience.

By Seyi Lasisi

While in transit to Ibadan, the haven of the two-year running Ibadan International Film Festival (IIFF), there were three thoughts that flashed through my mind. The first was writing this festival dispatch – a condensed review of films I will see at the festival. There is an inexplicable dread to expressing coherently, words to describe my thoughts in such a succinct manner. Second is the need to identify an overlapping theme amongst the films scheduled for screening. Pinpointing motifs has been the emblem of a festival dispatch but what critics have over time conceded is that this passionate investigation is often a futile endeavour. Lastly, as I moved toward the film festival venue, I realised how privileged I was to be a part of the screening audience. The lucky ones, one might say. Film festivals have always been a sanctuary of discovery. Whether aware or not, the audience enjoys a rare privilege. Beyond the filmmakers’ circle, they are often the first batch of people to see a film. So, while I subtly dreaded writing about the films I would see, I was comforted with the realisation that, in attending IIFF, I might be amongst the first audience watching a filmmaker’s production.

(Read more: Highlights from the Second Edition of the Ibadan International Film Festival(IIFF))

A total of 26 films were screened, including documentaries, animations, feature-lengths, and short films from Europe (Spain, Russia, Germany, United Kingdom) and African countries, such as Ugandan, Cameroon, and Ethiopia. The IIFF curated a list of films far removed from the Nigerian reality, however, as the screening which spanned three days, continued, the films indicated the depth and span of filmmakers’ efforts in the world. Amongst the 26 films, there are some that the audience could walk out of the screening room in protest and there are those that even one’s bladder was on the verge of explosion, you passionately sit through to the end. Although the films screened at IIFF are of varying degrees of success and failure, each film will eventually find its audience.

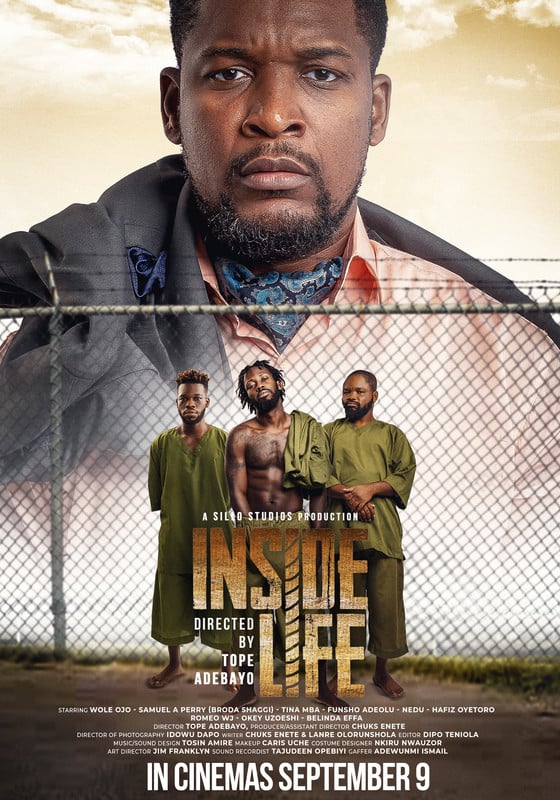

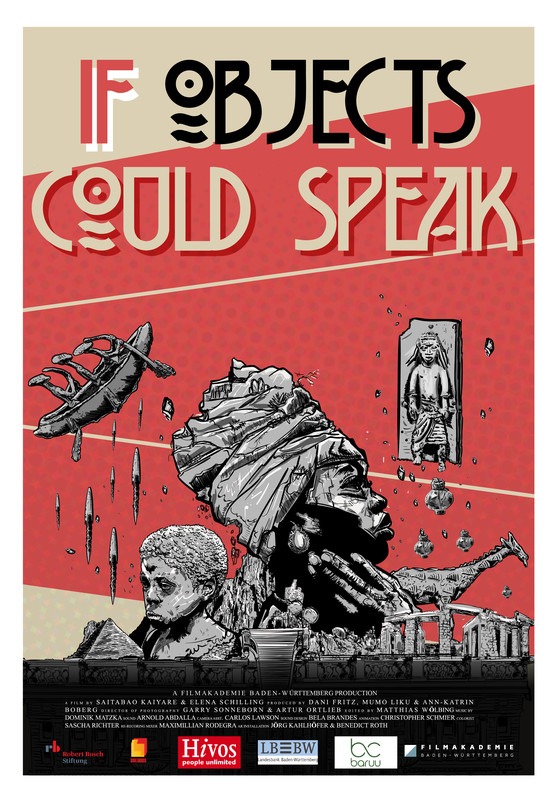

The majority of the selected films are social critiques of diverse issues. Saitbabo Kaiyare and Elena Schilling’s documentary, If Objects Could Speak recounts a prevailing conversation about restoring African artefacts back to their home countries. Dr. Odessa’s Baghdad Graphic, from Iraq, found itself walking through the aftermath of war and the trauma that follows. The Tope Adebayo-directed Inside Life is a cinematic exposition on police brutality and the dissipation of justice in the Nigerian legal system, and there is the Ukrainian Why am I Alive, which casually details, amongst other political and historical affairs, the conflicts between the Jews and Christians. This dispatch is an ode to the 11 films I was able to see at IIFF.

Feature Films

Inside Life – Directed by Tope Adebayo (Nigeria)

The Tope Adebayo-directed film is a parody of the Nigerian justice system. The film, which tells the unfortunate tale of a middle-class man, suggests to viewers how fragile or non-existent the Nigerian justice system is. Although the film, through dull comic scenes, occasionally loses grasp of the theme it chooses to address, it could pass as a critique of the justice system in Nigeria. It was also soothing to witness how Adebayo tamed Samuel “Broda Shaggi” Perry’s frenzied acting in one of the film’s scenes.

L’axe Lourd (The Highway) – Directed by Nkeng Stephens (Cameroon)

L’axe Lourd is hard to place. The story follows three – or perhaps one — criminals. It is difficult to say as the story gets convoluted as each scene unfolds. There is a national treasure (a precious stone ) touted as having supernatural powers, and one of the criminals becomes saddled with the responsibility of stealing the precious gem. The film juxtaposes modern times with an African mythological story. On the list of commendable aspects of the fast-paced film is its cinematography and editing. As the credit list starts rolling, I wish the filmmakers had paid genuine attention to the story’s development as they did to the cinematography and editing.

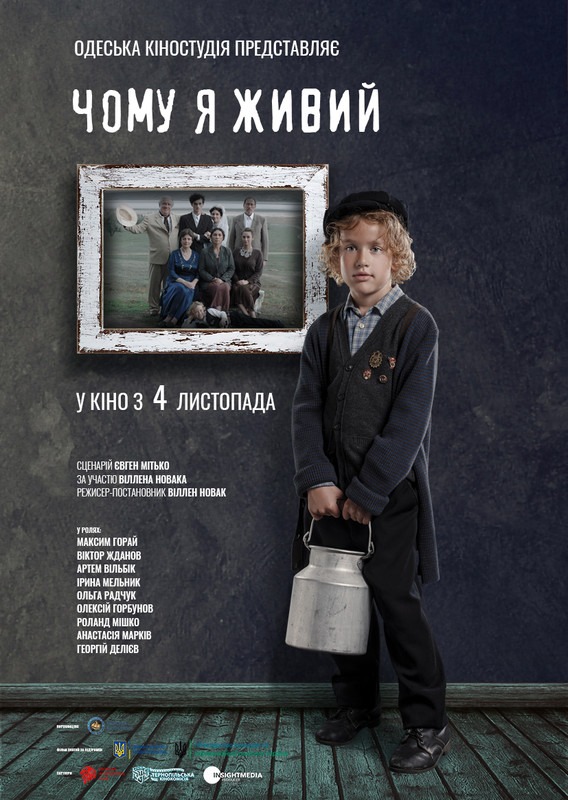

Why Am I Alive (Ukraine)

Oleska, the film’s lead character, is a troubled old man. And contrary to what the film might suggest, Why Am I Alive is not just a mundane story about an angry man burdened by his daughter, Zhenka, who won’t listen to his advice. The story, reflective through the man, is a walking totem of a dying but strongly held tradition steeped in stereotypes and hatred towards the Jews. As narrated from the naive point of view of Zhenka, a child actor worth seeing on screen constantly, the film engages this decade-long hostility towards Jews.

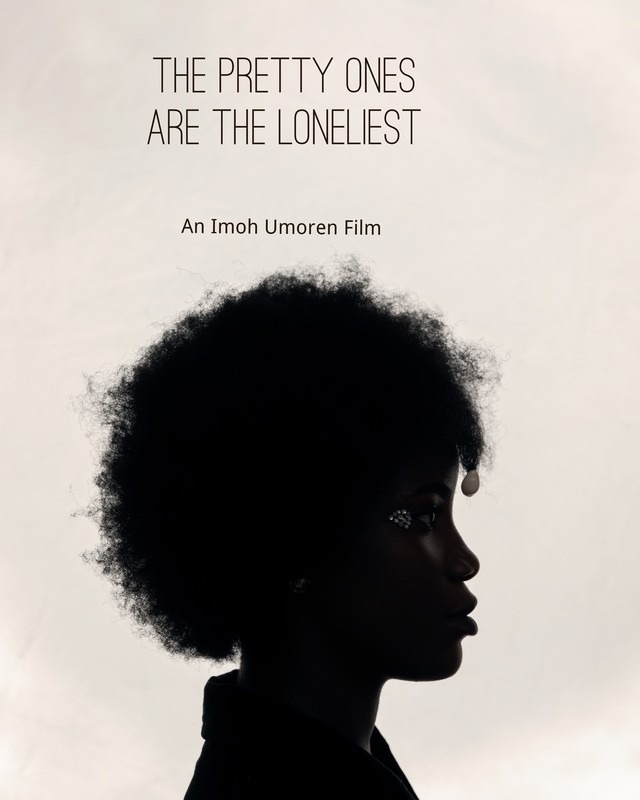

The Pretty Ones Are the Loneliest – Directed by Imoh Umoreh (Nigeria)

The title is quite literal enough, but when the film starts screening what is unfolding occasionally slopes away from the suggested title. But that is not a problem. The problem is how the film explores a range of themes but fails to coherently address any. When the film starts, a scene portrays the hostility between Bassey and his stepfather, Tamino. Following this closely is the theme of domestic violence. Tamino is growing distant from his wife, Bibi, hence her loneliness. While all issues compound, the film manages to smuggle in another subplot: Bassey is attempting to woo, for his grandfather, a lady he loves. Having multiple subplots is an offence in itself, but The Pretty Ones Are the Loneliest transgresses in its inability to handle any particular one.

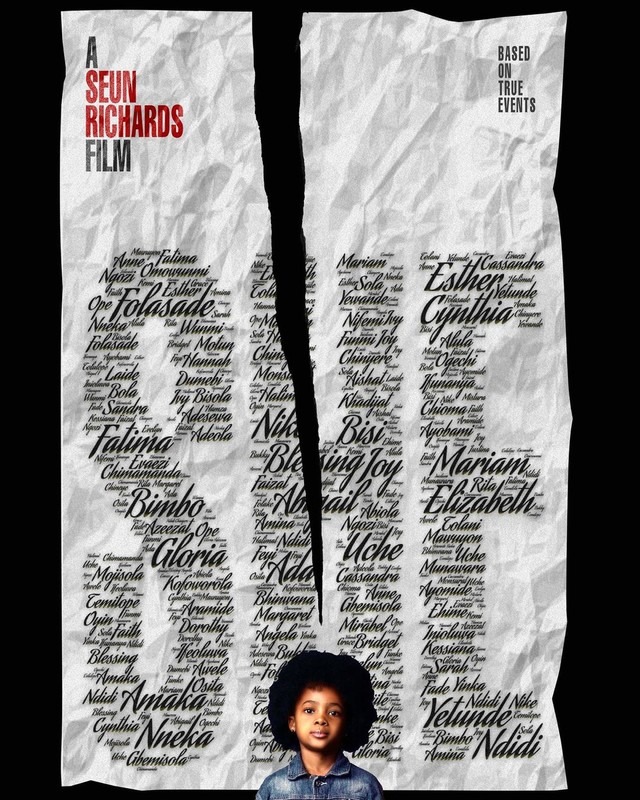

She – Directed by Seun Richards (Nigeria)

Child abuse and gender-based violence, as horrific and traumatic as it is, is prevalent. Rarely does a day go by without a report of child abuse or gender-based violence. Treading the sensitive topic of violence targeted at the female child is the emotionally demanding She. The film shows how prevalent child abuse is in society and how its perpetrators are often family relations, friends, and neighbours who want to integrate themselves into the lives of their victims. The film did a decent job of handling the sensitised theme with depth.

(Read more: “The Wildflower” Review: Biodun Stephen’s Winning Stream Continues in New Film about Gender-Based Violence )

Documentaries

If Objects Could Talk – Saitbabo Kaiyare and Elena Schilling (Germany)

Saitbabo Kaiyare and Elena Schilling’s documentary revolves around an important issue. It is no news that African artefacts are locked away in European museums, and there are ongoing talks and protests calling for their return to their land of origin. Kaiyare and Schilling’s If Objects Could Talk concern itself with this and more. The documentary, despite its subtle concern for returning African artefacts to Africa, is more invested in exploring whether Africans can recognise the long-lost artefacts and the cultural significance these objects hold.

Baghdad Graphics – Directed by Dr. Odessa (Iraq)

Dr. Odessa’s documentary is one about a national and universal tragedy. War has often been known to court horror and what this heart-wrenching documentary does is revisit such horror. This documentary retraces the protracted armed conflict that took place in Iraq from 2003 to 2011 with the invasion of Iraq by the U.S.-led coalition. What is however striking is how the filmmaker decides to present horrific scenes. The documentary uses graphics to dramatise the narrative of Dr. Odessa.

The Light in My Eyes – Mohanad Diab (The Netherlands)

Mohanad Diab’s The Light in My Eyes can best be described as a collection of stories about people living with varying degrees of visual impairments from around the world. The documentary features subjects from Ghana, Botswana, Uganda, Palestine, Egypt, South Africa, and The Netherlands. Although of different ages, the subjects of the documentary are connected in their optimism and zest towards life.

Short Films

It Happened Again – Directed by Ibidunni Oladayo (Nigeria)

Since the death of Nigerian production designer, Pat Nebo, I have developed a fascination for understanding how a set design of a film aligns with the story. And in one of the scenes in It Happened Again a disarrayed room captures beautifully, the sense of abandonment. The film is yet another portrayal of police brutality. But the traumatic moments aside, Nigerian actor Chimezie Imo’s commendable acting and the film’s sound design are the gems of the short film.

What Muffles Between Our Walls (United States)

The film is told through the point of view of a boy growing up in a family prone to domestic violence. We follow through with his emotional response to the violence in his family. The film allows the audience to witness the violence through the boy. There are no visible punches or blood. But, through the disturbed countenance of the boy, we bear witness to the violence.

In the Stillness – Directed by Naira Adedeji (Nigeria)

Judging from the multiple roles Naira Adedeji occupies in In the Stillness – as writer, director, and actor – one can opine that the film is partly autobiographical. Wura, the character played by Adedeji, encounters violence from her boyfriend, Jubril (Ibukun Omotowa). The plot of this short film is hazy. However, what becomes subtly clear is this: Chaos lies in the stillness of lovers’ embrace.

Seyi Lasisi is a Nigerian student with an obsessive interest in Nigerian and African films as an art form. His film criticism aspires to engage the subtle and obvious politics, sentiments, and opinions of the filmmaker to see how it aligns with reality. He tweets @SeyiVortex.