Ekwensi’s real forte is books for younger readers; the stark evidence of his works shows that his temperament and abilities were best suited to writing for that demographic…

By Chimezie Chika

In 2017, the year I left the university, my project supervisor, Professor Ernest Emenyonu, a preeminent literary scholar, took a liking to me, and, among other startling acts of benevolence, granted me access to his extensive private library. One of my first discoveries when I began to use the library was that the old professor had written extensively on the writer, Cyprian Ekwensi. He repeatedly emphasised that Jagua Nana, Ekwensi’s second adult novel, was a masterwork, the culmination of his storytelling genius. Curious about this luminescent praise from a scholar of his stature, I decided to take a little time off my project research to read Ekwensi’s Jagua Nana.

Like most bookish children growing up in Nigeria between the 1970s and 2000s, I had read many of Ekwensi’s books as a boy. It began when my mother narrated the fascinating story of An African Night’s Entertainment when I was nine. The book was not available in our house, but my mother’s narration of the story came from her own memory of reading it as a schoolgirl many years before. An African Night’s Entertainment, which was published in 1962, is an adventure story about Abu Bakr who goes on a journey to take vengeance on Mallam Shehu for poaching and marrying his beloved betrothed, Zainobe. He endures several dangers and hardships and hatches plan after plan to achieve his aim. His final plan was to make Kyauta, the child of Mallam Shehu and Zainobe worthless, which he achieves at a great expense. The foundation of the story comes from an old Hausa folktale which Ekwensi claimed was told to him by an old mallam when he was young. Ekwensi carries that strong ambience of folklore into the story. As the story progresses, one feels its mythic elements take centre-stage in a manner that is utterly riveting to any young reader.

Enthralled by my mother’s narration, I begged her to get me a copy of it, which she did. From that point, I became very interested in reading everything Ekwensi had written that I could lay my hands on. I would go on to read Drummer Boy (1960), The Passport of Mallam Illia (1960), Burning Grass (1962), Juju Rock (1966), Samankwe and the Highway Robbers (1972), and Trouble in Form Six (1966). I enjoyed these stories for the sheer paradoxical exoticity and familiarity they hold. I had never read anything like them before: they had Nigerian characters and settings — a first for me, since I had been reading foreign fiction with foreign characters and settings until that point — yet they captured experiences and events far removed from what I had known.

(Read also: Is Nigerian Literature Truly Dying?)

For many Nigerian readers, Ekwensi is perhaps the most accessible author from the first generation of Nigerian writers. Many praise his work as a strong influence on their childhood, youth, and early education. In his time, his books were extremely popular among African readers. Early reviewers of his novels in the 1950s and 1960s, while cautiously focusing on the subject matters, praised them as exemplars of life in colonial Africa. In the late 1970s and 1980s however, critics began to find his work inadequate in its application of literary elements. The likely reason for the more rigorous scholarly engagement with Ekwensi’s works in the 1980s would likely have been the change in the emphasis of African literature from quantity to quality. Ekwensi’s work represented a period when quantity proved important to fill the gap in the representation of Africa in literature.

This is perhaps why, even though he remains one of Nigeria’s notable writers, Ekwensi has always elicited conflicting opinions about the true significance of his works. In recent times, it has become an annual event in the Nigerian literary community on social media to debate whether or not his works have any literary merit. One school of readers see Ekwensi works as unarguably great in every respect; another school consider his work deeply flawed, citing the poor quality of his writing. To state it more squarely: Do Ekwensi’s works possess literary merit? As a person who has read a substantial amount of Ekwensi’s literary production, ascribing greatness or insignificance to Ekwensi’s entire oeuvre would show a lack of knowledge, since the writer himself produced a tremendous amount of work across genres during his career that spanned five decades.

Ekwensi’s first book, published in the UK in 1947 by Lutterworth Press, is the story collection, Ikolo the Wrestler and Other Ibo Tales. One of the earliest internationally published books by an African, the book is a collection of well-known Igbo folktales, albeit with little imaginative input from Ekwensi other than what he had recast from memory. The book’s unremarkable constitution marked the beginning of a prodigiously prolific career that produced more than forty books, including novels, plays, short stories, and children’s books. In the same year of his literary debut, Lutterworth Press, as part of its New African Writing imprint, published five other books by him. The next year, 1948, Ekwensi released a collection of light romance short stories through a publisher in Onitsha (He was one of the major drivers in the “Onitsha Market Literature” phenomenon, happening between the 1940s and 1960s, which saw the explosion of sensational and moralistic pamphlets and novelettes written by mostly semi-literate writers based in Onitsha and its surrounding areas).

His first novel, People of the City, was published in 1954 and, at the time, was only the second novel by an Anglophone West African to be published internationally, after compatriot Amos Tutuola’s The Palmwine Drinkard in 1952. People of the City follows the story of a young crime reporter who moonlights as a bandleader. While the novel’s narrative is loose and has little cohesion, resembling a story collection rather than a novel, it contains some of the most palatable descriptions of city life of the 1940s and 1950sWest Africa. As far as storytelling goes, Ekwensi would improve with age, especially with his plots. He had already published more than ten books by the time Chinua Achebe published his monumental novel, Things Fall Apart in 1958. None of what Ekwensi had produced prior came close to the formal accomplishment of Achebe’s book. Perhaps this very fact played a role in ushering in Ekwensi’s most productive period, the 1960s, the decade in which he produced all his best- known works, including his most famous Jagua Nana.

(Read also: Has the “Great Nigerian Novel” Been Written?)

Two of the novellas Ekwensi published in 1960, The Drummer Boy and The Passport of Mallam Illia, are now regarded as children’s literature classics. The Drummer Boy tells the story of Akin, a blind boy in Ibadan who has a remarkable musical talent. Ekwensi’s attempt at a künstlerroman of sorts, The Drummer Boy is his best book. Akin, his most fully realised character, is vulnerable and sensitive. Each errant encounter he has reveals an aspect of his sympathetic personality. The novel is also noticeably Dickensian in its use of the familiar trope of a poor boy, street urchins and pickpockets in a big city, exploitative adults, and a final act of rescue.

The Passport of Mallam Illia is another of Ekwensi’s novels that takes its inspiration from indigenous Hausa folklore and mythology. His knowledge of Northern Nigeria was vast; his writing brought some of that region’s most esoteric cultures into public consciousness. No other writer who writes in English has, arguably, been able to replicate what he did for Northern Nigeria. Like An African Night’s Entertainment, Passport is a vengeance quest narrative that follows Mallam Illia’s journey to avenge his wife, Zarah, who was killed by his nemesis, Mallam Usuman. The novel’s mythic elements add to this spellbinding narrative about a bygone era in Northern Nigeria, a time of chivalry and equestrian darlings. Of course, many of these romance elements are not rooted in the real world, they emerge from that folkloric magical universe that Ekwensi often inhabits in his tales. Burning Grass, another of Ekwensi’s notable novels set in Northern Nigeria, involves a Fulani family, several quests, chivalry, and a doomed love affair. From Juju Rock and Iska to Samankwe and the Highway Robbers, Ekwensi reuses the same tropes over and over again.

In his urban tales, the narrative moves away from the mystical into a world of secular experiences in the burgeoning African cityscapes of the colonial and post-colonial periods. Here we meet prostitutes, musicians, traders, politicians, and random urban dwellers caught in extraordinary experiences. Beautiful Feathers (1963) is Ekwensi’s portrayal of the vagaries of life on the cusp of independence in African countries. The novel follows Wilson Iyari, a successful man dealing with manifold marital problems while trying to stay relevant in the political arena. Carrying more thematic velocity than anything Ekwensi has written before, the novel has quite a lot going for it as far as relevance goes. There are socio-political and prescient feminist concerns here, which particularly highlight Ekwensi’s far-sighted vision. However, as we will soon find out, the problem with Ekwensi is never with his material or the heft of his thematic material.

Jagua Nana, seen by many as Ekwensi’s best novel, is one of such urban narratives. The narrative follows its titular character, an illiterate prostitute who rises to money and influence using her beauty and guile. She finally decides to settle down with a younger man who has other intentions. The novel is not lacking in provocative portrayals of the baser aspects of city life and the sensual allure of nightlife in 1950s Lagos. This last fact brought harsh criticisms of pornography and indecency on Ekwensi upon the novel’s publication in 1961, followed by bans by both the Anglican and the Catholic communities. These sorts of suppression are less frequent these days but were quite common up to the sexual revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s. Earlier writers like DH Lawrence and Vladimir Nabokov had to go through long legal battles over the subjects of their books.

(Read also – Ama Ata Aidoo: 10 Things You May Not Have Known About the Ghanaian Feminist Writer)

As I read Jagua Nana in the tranquil confines of Prof. Emenyonu’s library, I grew increasingly furious with Ekwensi’s anodyne insistence on stereotypes. Ekwensi’s Jagua Nana is the classic femme fatale; there is no depth to the character, her actions repeatedly fail to convince, and there is no intricate psychological structure to the relationships between the characters. Every single aspect of the novel falls flat in the face of Ekwensi’s desire to drive the plot. At best, the novel is little more than an incompetent thriller, which raised my curiosity about Emenyonu’s verdict about its greatness.

Writing in Studies on the African Novel, Emenyonu is at pains to show what makes Jagua Nana a great book. Much of his argument is based on Jagua Nana whom he claims is Ekwensi’s “most fully realised character”. All the evidence of that character however proves the contrary. Jagua is utterly predictable. She talks the same way every time, and despite Ekwensi’s attempts to portray her as a “strong” woman who has control over men, she appears weak and docile. That the novel won the Dag Hammarskjöld Prize in Literature in 1968 may say something about its satiation of popular reading tastes in its time, but there is no excuse for the manner in which Ekwensi overlooks the subtler elements of narrative with an obsessive fixation on the surface of the story.

Away from the vacuity of the characterisation, the novel teeters ever so much under Ekwensi’s poor grasp of craft. My keen interest in the plot was constantly broken by the quality of Ekwensi’s sentences. Is it too much to ask, I pondered, for this writer to maintain a decent level of sentence construction? The plot, too, is flawed, especially because of the stiff characters. But perhaps I am judging a popular writer rather harshly; Ekwensi was more or less Nigeria’s version of the mass-selling popular fiction writers who dominated bestseller lists in the West. But the worst features of popular fiction are exactly the opposite of great literature: poor characterisation, shallow adrenaline-filled plot, and lack of depth.

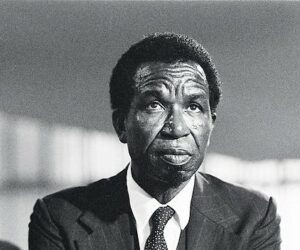

As a writer, Ekwensi’s adult novels bear no evidence of the artisanal mastery of the more technically adept writers of his age such as Achebe and Wole Soyinka, or even the now almost forgotten but accomplished short story writer, I.N.C. Aniebo. But where he lacked craftsmanship, he had an abundance of material and knowledge. Ekwensi seems typical of a man who had lived through multifarious experiences across all parts of Nigeria — he was born in Minna in Hausa/Fulani-dominated Northern Nigeria to Igbo parents, attended Government College Ibadan in the predominantly Yoruba Western Nigeria and worked as a forestry officer in many parts of Nigeria between 1945 and 1947 — and had accrued a lot of stories. From these experiences in his life, he had a lot of material to work with, perhaps too much, since he seemed interested in publishing as many books as possible rather than wasting precious time on crafting a perfect sentence.

(Read also – Flora Nwapa: The Lesson on Artistic Endurance)

Ekwensi’s real forte is books for younger readers; the stark evidence of his works shows that his temperament and abilities were best suited to writing for that demographic. He achieves incomparable brilliance in children’s classics like The Drummer Boy, The Passport of Mallam Illia and An African Night’s Entertainment. The singularity of his work in this genre is found in its evocation of nostalgia for bygone epochs of pre-colonial and colonial life, especially in Northern Nigeria. He was a master of the picaresque adventure novel for children driven by fascinating characters consumed by vengeance and wanderlust. The trope of peregrination in these tales is elevated to mythic tales of heroism. On this note Ekwensi’s crucial place as a pioneer in Nigerian literature is secure.

However, the moment Ekwensi pivots into adult fiction, the conscious reader finds endless problems with his writing. From Jagua Nana and its sequel, Jagua Nana’s Daughter, to People of the City, one encounters paper-thin characters rigid with stereotypes, narratives that lack nuance, and language that lack the rhythmic modulation of good writing. Ekwensi’s albatross in adult fiction is his fixation with a style that follows the structure of the morality tales of the Middle Ages in Europe, overlaid with a contemporary secular temperament and his recourse to simplistic resolutions as if his readers lack discernment. The movements of his narratives pursued this singular attribute with vigour and inattentiveness.

The great American essayist and critic, Susan Sontag, once said that “a novel worth reading is an education of the heart. It enlarges your sense of human possibility, of what human nature is, of what happens in the world. It’s a creator of inwardness.” I will go further to say that “inwardness”, as Sontag iterates so illuminatingly, is the true character of great literature. We understand literature through a perception of who the characters are in relation to the physical and psychological realities of their environment. You gradually come to “know” the characters from their inner lives which are shown to you through their actions, words, and thoughts. You recognise the imprints of their actions or pre-empt their future actions, the same way you do for people you’ve known all your life.

All these come from the subtle revelations of the interiority — the “inwardness”, so to speak — of the characters through the means of narrative. The painstaking portrayals of ambience, feeling, motivations and events; the capturing of the deep melancholy that undergirds human life and the emotional connections that keep us sane in an insane world — these are the primal qualities of great literature, the very elixir that we, as writers, seek; he who finds them has created something for all ages. So is there literary merit in Ekwensi’s works? Without a doubt, Ekwensi was a great storyteller, but this only completely applies to his children’s books. In the more technically demanding adult category, his storytelling talents fade through the poor grasp of other elements that make enduring literature. On that note, Ekwensi’s adult works are important in the catalogue of Nigerian fiction, but they are not great.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Republic, The Shallow Tales Review, Iskanchi Mag, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Efiko Magazine, Brittle Paper, and Afrocritik. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1