Power Mike retired early as a professional wrestler in 1976 with a fight record of 125 without recording a single defeat. He entered wrestling promotion, helping to shape wrestling in Africa…

By Chimezie Chika

The Apprenticeship Years

Even in the most ordinary days of our lives, when we are only interested in grinding through our work for the day, it sometimes comes to us as a note of encouragement: “Power Mike, strong man, jisieike, keep on.” Energised, and wanting to prove that those words are no fluke, we continue with whatever menial or skilled work we are engaged in. Those words, “Power Mike,” used in everyday language to mean power and strength, once belonged to one of Nigeria’s most storied personages of the 20th century. “He brought wrestling to us,” Ben Udeogu, an Onitsha resident who lived in Lagos in the 1970s, said.

His story begins, as all such stories do, with his birth on August 8, 1939 to Echeobi and Janet Okpala at Neni in the state of Anambra. Christened Michael, his childhood was, by most extant accounts, unremarkable. Neni, in the 1940s, was hard and unyielding, sustained by the people’s resilient subsistence on farming. In the post-World War II urban boom that ensued in the 1940s and early 1950s, young men left the villages as they came of age. And so it was for the young Michael Okpala, who left Neni in 1952 after completing primary school at Anglican Primary School, Adazi-Enu, a neighbouring town.

(Read also: What is Humanity’s Fuss about Strongmen?)

The last years of his primary school education were marked by Michael’s spirited involvement in sports and athletic activities in which he excelled. These physical successes, though, did not encourage a further stay in school. The future — what his parents and his kinsmen saw — was in the booming market town of Onitsha where many a young country bumpkin, with heart and focus, could make his fortune. Michael Okpala left for Onitsha in 1952 at just thirteen to seek his fortune as an apprentice to a fabric dealer at the famous Onitsha Main Market.

The bristling energy in Onitsha suited him well. Activities never stopped; the city’s wheels churned with purpose within its agile limits. At the market, Michael lifted bales of clothes and other heavy items with such enthusiasm that it was soon clear to everyone that the young man had a more than average strength. Two years into his apprenticeship, a buddy introduced him to the Dick Tiger Boxing Club, where he began to train as a middleweight boxer. Dick Tiger, a professional boxer who would become very famous in the coming years, became his role model. Though he had not heard about Dick Tiger up until then, Michael was glad that there was a countryman already far ahead as a sportsman.

Michael Okpala spent his days at the club, training. It was such that reports came to his master of his apprentice’s activities. It was not clear, in individual accounts, whether there was an altercation, but the inference is that there was. “Intense training like that consumes a lot of time,” Gee Pee, a boxing enthusiast based in Enugu tells me. “You have to come every day and put in a strong shift. You must have a routine and not skip training. This is what I have learnt.” It is understandable then what Michael Okpala, in the years of training at the Dick Tiger Club in Onitsha, was compromising. It was always clear that in such situations, compromise is inevitable.

He left Onitsha for Kano to start learning a trade in tire dealership from a kinsman in the trade, residing in SabonGari. He soon got himself apprenticed to a motor mechanic, perhaps unconvinced about his prospects in the tire business. Most likely, he was in some sort of existential crisis, involved in a never-ending search for his true purpose, a place where he could fit perfectly without forcible exertions that are disagreeable to his person.

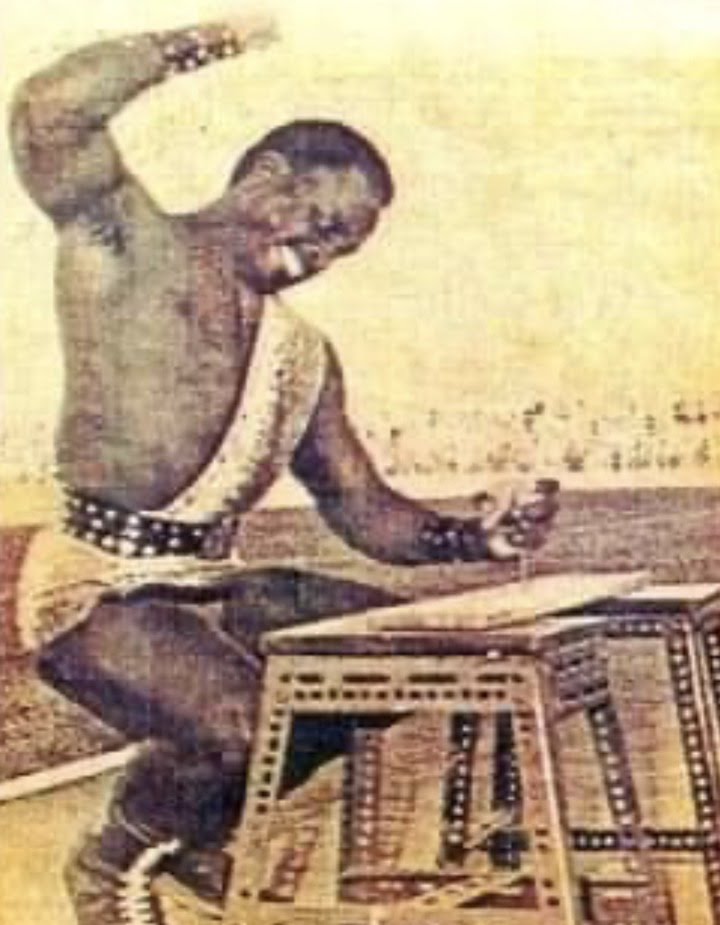

As the story went, at the mechanic workshop, he would lift engines and heavy motor parts with relative ease. His fellow mechanics and the people around his neighbourhood began to call him Power Mike as his popularity as a strong man grew. The way in which these feats came to him made him realise that he might fare better pursuing a career that utilised his physical strength. From there, he moved throughout Nigeria performing feats of strength in public road shows, which were popular in those days. In some accounts, these feats were sometimes covered in mythic terms; in one he was said to have halted the movement of two Volkswagen 1300 by means of a rope tied to their bumpers. In another, he drove a six-inch nail into a piece of wood with his bare hands

The Heydays

A national tour in 1961 took him to Port Harcourt, Enugu, Onitsha, Aba, Jos, Kaduna, and Lagos. By 1964, collaborating with local wrestling promoters, he began to tour internationally within Africa, visiting Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal, defeating all his opponents. The activities at these tours were rather eclectic, involving amateur wrestling, power shows, and weightlifting.

From this point, Power Mike’s story begins to read like a fast-paced riveting thriller with a larger-than-life protagonist. A one year contract that came from Sweden, secured by one of his promoters (Power Mike was the toast of sports promoters at this point), saw him move to Europe where he became widely successful, with European scouts urging him to leave vaudeville performance and train professionally as a wrestler, a career which, in their view, he was naturally endowed for.

With that in mind, he moved to Greece. Greece then had a reputation for producing world famous wrestlers. There, where he was sometimes called the African Hercules (Αfrikanikos Iraklis), Power Mike began to train professionally. In the ensuing years he would win bouts against some of the most famous wrestlers of the late 1960s and 1970s. His first famous professional win was against the Greek Heavyweight champion, Paparazallo. Most older men in Anambra that I talked to remember the news of this fight very well; perhaps it is the only thing they remember, for further prodding usually yields nothing more substantial than the ecstasy of eulogies. “He defeated the huge Greek,” they said each time.

Those defeated in Power Mike’s long line of triumphs include the then Commonwealth champion, Joseph “Kingpin” Kovacs, Jude Harris, Lee Sharon, and Johnny Kwango, who was famous for his deadly signature head-butt. Media coverage of Power Mike’s fights in Europe and America (where he fought at the Madison Square Garden in New York) in the 1970s Nigeria and Africa were so sensational that, even though the knowledge of modern pro-wrestling was then almost nonexistent in the Nigeria, it did not deter people from rallying around their famous countryman. There were widespread calls for Power Mike’s triumphant return, to be occasioned appropriately with a wrestling match.

By far, Power Mike’s most famous match-ups were against the over six-foot and 266 pound Lebanese wrestling champion, Ali Baba, whose story has even entered Nigerian lore, so that there are people who go by the name these days. Their first fight was at the Nakivubo Stadium in Kampala, Uganda in 1973, where Power Mike won the World Heavyweight title after inflicting a straight defeat on his opponent. The first match in Lagos in 1975 was Power Mike’s first title defence as World Heavyweight Champion. Crowds thronged at the National Stadium in Lagos. The arena was so packed that some people hung on the fences. It was an intense, keen fight of equals, but Power Mike soon got his opponent into an impossible position, finally ending in a double knockout. The stadium erupted in a loud joyful clamour. (It is possible that they did not understand what the final score meant.) All ambiguity will be put to rest when later that year, in a rematch at the Sports Hall of the National Stadium, again in Lagos, Power Mike finally defeated Ali Baba in a clean knockout. Okwudili Olisakwe, a young man from Adazi-Enu, tells me that his father witnessed some of Power Mike’s fights in Lagos: “My father said that those matches were an obsession for them at the time. All I know is that I grew up hearing stories that Power Mike had so much physical strength.”

(Read also: The Legend of Ogbanje: Superhuman Abilities, Wanderlust between Life and Death)

Street Legends

Power Mike retired early as a professional wrestler in 1976 with a fight record of 125 without recording a single defeat. He entered wrestling promotion, helping to shape wrestling in Africa. The tournaments he organised drew wrestlers from Africa, Europe and America. The prevalence of European and American wrestlers in these tournaments sometimes drew criticisms from some Africans who felt he was privileging the west. He defended these charges by saying that foreign wrestlers drew large crowds, which helped to cover overhead costs. In his heyday, Power Mike was the toast of many African governments. He met with, amongst other leaders, Milton Obote of Uganda, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and Kenneth Kagunda of Zambia, who called him “a great ambassador of the black race.” In Power Mike’s hometown, he was bestowed with a chieftaincy title: “Ide,” meaning “pillar” in Igbo.

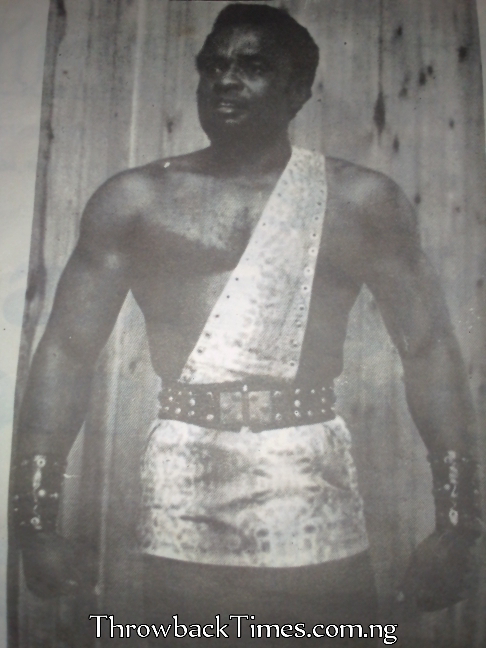

In Neni, standing at the traffic centre of the town, at Ọkacha junction, on the road to Awka, is a huge concrete statue of Power Mike, standing tall and muscular like a Greek marble titan on a citadel of some ancient Ionian island. Power Mike’s statue in his hometown, obviously of no Hellenic origin, had been sculpted from one of his more famous photos, after a famous victory, holding his right hand aloft in acknowledgement of the ecstatic crowd around the ring, one leg slightly forward, showing that he was clearly in motion, perhaps walking about the ring in the adrenaline flush of victory. “They made it after his death in March 2004,” a Neni indigene tells me.

On a mildly sunny morning that promises to be hot, I set off for Neni via the Nkpor route through Obeledu and Nimo. My first trip to the town had yielded little fruit. On enquiry I was told, in a decidedly obscure language, that the Okpala family was not around. Any member of the extended family I could talk to? I asked. None, my respondents said. I went home that day knowing that I had been probably blocked by the people I talked to for security reasons. It was not surprising, given how much insecurity has risen in the state. It was there in the blank faces, in the darting glances, in the increased guardedness.

On this second visit I went to a bar and sat down with a warm bottle of beer (They had no cold ones. NEPA, they complained). There were three other men in the bar who were talking politics over bottles of beer. Uncertain at first, I tentatively joined in. Through the heated arguments around the recent 2023 national elections, I wallowed in the dilemma of quest. How do I introduce my topic without sounding suspicious? Time passed, I ordered a round. The bar echoed with appreciation. “Iyoo, Daalụ!” I was now the object of interest.

You are not a familiar face here. Who are you? They asked. More people had entered the bar. I hesitated a moment and introduced myself truthfully. “Ah! Power Mike is a legend,” the first man with white streaks in his beard said. He seemed to drag his voice, possible signs of inebriation, but he told good stories. One by one they began to say what they knew of the most famous person from their town. This was no formal interview anymore, more like a town hall meeting with voices echoing matter-of-fact opinions, sometimes repeating the same things over and over: “great,” “strong,” “legend.” “I didn’t know Power Mike was a real person until I came here,” Sunday, an Okada cyclist originally from Ezzamgbo in Ebonyi State said. The uniformity of information overwhelmed me. What had I expected? “Write about him well oo,” White-Streaked Beard said as I left and walked into the scorching sun of an ordinary day.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik, and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.