The Internet became very popular in Africa in the early 2000s. The coming of the Internet corresponded with an unprecedented explosion in the number of literary magazines in Africa…

By Chimezie Chika

The Great Beginnings

In the tail end of 1957, a group of ambitious students and staff of the University College Ibadan got together and began a students’ poetry magazine called The Horn. Ibadan, in the 1950s, was more or less the melting pot of budding artistic expressions in the colony of Nigeria, and the University College Ibadan, one of the few universities in Africa at the time, was incubating, within its walls, a group of young writers who would shape the future of Nigerian Literature. The four students who had gathered to form the magazine at the encouragement of one of their teachers, Martin Banham, were led by a young man called J.P. Clark. He was short-statured and had a quick gait that betrayed a forceful personality. The other three were Bridget Akwada, Aigboje Higo, and John Ekwere. The students were poor and inexperienced, but they had their heart set on what they wanted to do. Martin Banham provided financial support, and they borrowed the English Department’s typewriter. Together, in January 1958, they managed to put out the first issue of The Horn.

The Horn was little more than a ragtag publication. Robert Fraser wrote in West African Poetry that it was “skimpy in presentation.” It was a collection of typewritten foolscap sheets stapled together to form something that resembled a book. To raise funds, it was sold for two pence a copy, and later three pence after the third issue. This issue of funding would remain, till date, a common denominator in the running African literary magazines.

(Read also: How the Traditional Publishing Industry in Africa is Shaping the Emergence of New Voices in African Literature)

The Horn was not the first full-fledged African literary magazine published in English. That honour goes to Black Orpheus, which was founded in September 1957 by Ulli Beier, a German lecturer in the Department of Extra-Mural Studies at the University College Ibadan. The magazine borrowed its name from a 1948 introductory essay by Jean-Paul Satre, “Orphee Noir,” published as part of a poetry volume edited by Leopold Sedar Senghor. In the maiden issue of the magazine, Ulli Beier explained in the editorial statement that the magazine was motivated by a need to provide a platform to make the work of emerging African writers across all language barriers visible.

Until its final issue in 1975, Black Orpheus published poetry, fiction, art, literary criticism and commentary, and was edited, at various points in its existence, by notable African intellectuals such as Wole Soyinka, Es’kia Mphahlele, and Abiola Irele. It published the early to mid-career works of notable African writers and artists, including Wole Soyinka, J.P. Clark, Dennis Brutus, Ama Ata Aidoo, Alex La Guma, and Francophone writers such as Birago Diop, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Aime Cesaire, and others, who were published in translation. The literary critic, Irele, would write years later that the influence of Black Orpheus on African Literature was as groundbreaking as it was extensive; “if it did not directly inspire new writing in English-speaking Africa, at least [it] coincided with the first promptings of a new, modern, literary expression and reinforced it . . .”

The Horn and Black Orpheus were important for a number of reasons. Their goals were quite modest: to provide a stage for the blossoming of new writing. Notable in all such rhetoric is the identification that literary magazines are integral to the growth and sustenance of a robust literary culture. Many budding African writers in the late 1950s and 1960s owe their first publication to these magazines. For writers, first publication — no matter how small, despicable and unremarkable — are always important for the confidence they bestow.

Before all these efforts in the Anglophone world, French-speaking Africans had a significant head-start in magazine publishing with the founding of the highly influential Presence Africaine in 1947 by Alioune Diop, a Senegalese professor of philosophy, in what was most probably the first African literary magazine in any language. The magazine had a pan-Africanist outlook and was instrumental in the Negritude movement and in the anti-colonial movements of former French colonies. While the magazine was published predominantly in the French language, between 1955 and 1961, it also published an English-language edition that ran to 60 issues.

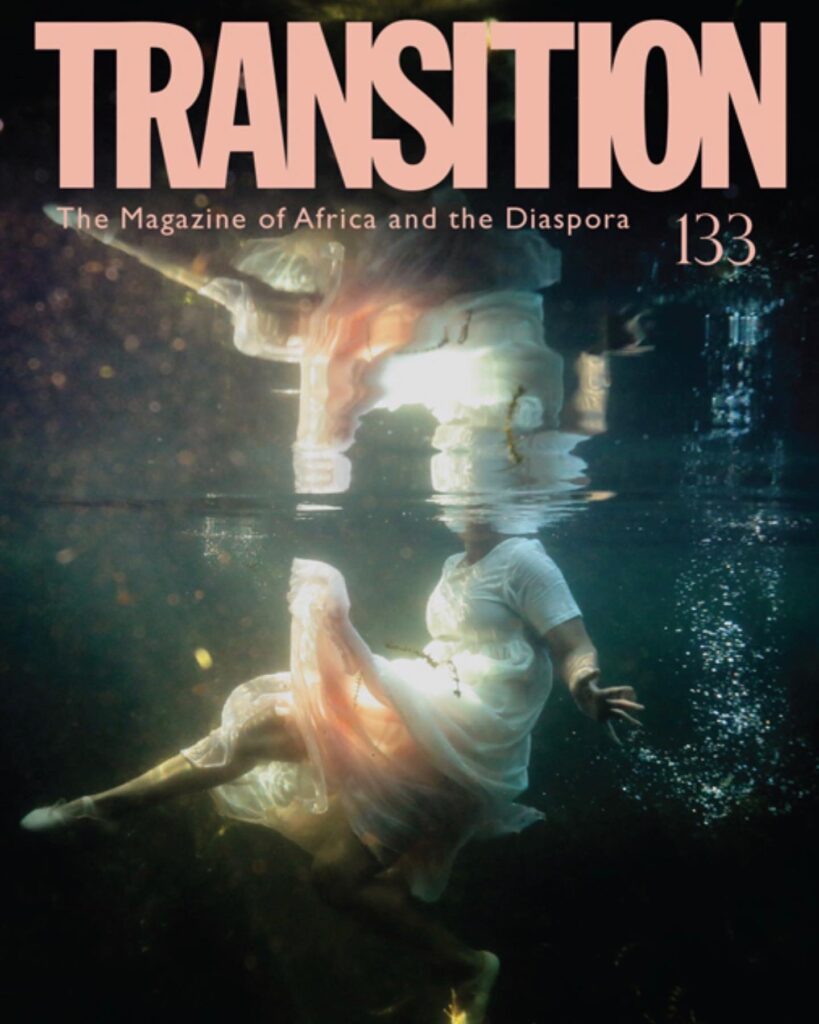

In Anglophone Africa, Black Orpheus opened the floodgates of literary magazines. Over the next few years, many were founded. There was Okyeame, a literary magazine based in Ghana, which appeared between 1960 and 1972, initially edited by the Ghanaian poet, Kofi Awoonor. There was Transition Magazine, which was established in 1961 in Kampala, Uganda by Rajat Neogy, who “wanted to provide a space where different ideas could meet.” Transition is often regarded as one of the most important literary and cultural magazines to come out of Africa. It not only published generational voices such as Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Wole Soyinka, Ali Mazrui, and others, but became an institution of cultural and literary transit, as its intriguing title suggests. Transition was published in many parts of Africa between 1961 and 1976, when it ceased publication for financial reasons. The magazine was revived in 1991 at Harvard University by Henry Louis Gates Jr., and has since joined the ranks of preeminent magazines in world literature.

There is also The Muse, the oldest surviving student literary magazine, founded at the University of Nigeria Nsukka in 1963 by Chinua Achebe, who was then a lecturer at the university. Achebe had also founded, in 1971, Okike: an African Journal of New Writing which housed the works of many notable writers across Africa. Achebe may have recognised that the university can be a nurturing environment for artistic growth. Much has been said and written about creative writing in universities. In Chad Harbach’s famous essay in n+1, he concludes that creative writing in universities advances literary culture in dynamic ways. Cheta Igbokwe, playwright and editor of The Muse no 48, told me that given a university English curriculum that favoured academic criticism at the expense of creative writing, the magazine has provided a much needed outlet for creatives. “Student magazines are important. Even as important as those in the mainstream. I think a magazine should be measured in how far it has kept to its founding goals, if that is the case, then The Muse has continued to succeed. Many of Nigeria’s wave-making writers in the present and in the past have had a connection with The Muse.”

The early years of magazine publishing in Africa was marked by an undercurrent of intellectual fervour to lay the groundwork for the emergence of distinct literary cultures and movements. There was an understanding that the literary culture of Africa was young and lacking, and prominent African writers and intellectuals seemed driven by such grand schemes to remedy it. There was also the need to create repositories where only emergent works and indigenous African thought were dissected. This was the motivation behind magazines like Transition. Each magazine created distinct styles, approaches and institutions around them.

Despite the noble origins of these literary magazines, little remains of most of them. Of all the magazines mentioned so far in this essay, only Transition and The Muse remain in print. The rest have fallen not so much into oblivion as into the static glory of history. While they impacted the African literary space in their time, they were driven to close shop by factors that were mainly financial and partly managerial. If there is anything to be learnt from the magazines that have survived, it is that they found permanence in institutional support: Transition is now firmly domiciled at Harvard, and The Muse is entrenched in the English Department at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

The Age of Digital Publishing

The Internet became very popular in Africa in the early 2000s. The coming of the Internet corresponded with an unprecedented explosion in the number of literary magazines in Africa. The ease with which websites are created in the post-millennial age also meant that anyone could easily start a magazine by designing onsite graphics. Some of the most influential African magazines of the 21st century began in the early years of the new millennium.

(Read also: The Architecture of Literary Prizes: What Does the Future Hold for the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature?)

Binyavanga Wainana’s Kwani? heralded a crucial period of change in Africa’s literary future, introducing many new African writers who would headline the new age. Kwani?’s emergence in 2003 was an event. Emerging from the stagnant literary culture of the 1990s, it created a bubble in sub-Saharan Africa — together with the Caine Prize, and The Chimurenga Chronic which was established in 2002 by Ntone Edjabe — and began a literary revival in Africa. Suddenly, there were an abundance of literary workshops, festivals and prizes. Kwani? had the Kwani? Manuscript Prize and other initiatives. Chimurenga projects a quasi-Jazz-Reggae aesthetic, cutting across literature, politics, and music. African Writer, the earliest African digital-only magazine, was started in 2004 by Sola Osofisan; having published many notable writers in its heyday, its unique status certainly cannot be ignored. The notable thing about these pacesetting African literary magazines of the 21st century is that they are still publishing.

In the years since, many magazines have come and gone. Between the late 2000s and early 2010s there was Sentinel Magazine Nigeria, Kikwetu Journal, and Saraba Magazine. Problems have been identified. Many of these magazines do not have a strong enough managerial team, permanent stream of finance, or a sustained ideological outlook. It could be argued that the failure of many digital magazines in the 21st century is a downside of poor values and finances. Saraba was magnificent while it lasted. Its managers approached its production with clear passion. “Our foray into digital publishing was motivated by personal gains,” wrote poet and co-founder of Saraba Magazine, Dami Ajayi, in “The Necessities and Exigencies of Digital Publishing,” a speech he presented at the Digital Africa Conference at Amherst College in 2017. He and Emmanuel Iduma had started the magazine after they met at a colloquium at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife in 2008. Motivated by the need to have their work in print, they quickly produced the first issue in 2009. What began as a personal venture gradually transcended them. Saraba would contribute immensely to the literary culture (its last great act being the Saraba Manuscript Prize) but, ultimately, it would close.

Why did Saraba, and many like it, close down, I asked Ajayi. “Literary magazines die. This is just the truth of it. If you look at magazines that survive and the ones that die, you’d realise that the models we are using are not sustainable. We need to figure out how the money comes out,” he says. “A lot of people start literary magazines as a response to the frustration of not being able to publish. And then you start the magazine, it picks, but then how do you sustain it?” He adds: “Magazines are victims of the failure of publishing houses. As these organisations begin to fail, the literary magazine is the first to be cut. This is what happened to Farafina Magazine, and many others around the world. Recently, it has happened to Catapult too. It is not just an African thing.”

As the story of literary magazine publishing comes closer to the present, it becomes more and more grim. But there are a number of literary magazines from the early 2010s that have braved the odds and created their own workable models of sustenance while still confronting the problems of their predecessors. Among these magazines are The Kalahari Review, Brittle Paper, Omenana Magazine, and Bakwa Magzine. Brittle Paper, which was started by Ainehi Edoro in 2010, while she was still a PhD student, became the go-to site for news on the African scene. Before Brittle Paper there was no attempt to document the contemporary African literary scene on such an extensive scale. Derek Workman, founder of The Kalahari Review, started the magazine in 2012 after he returned from the United States. “In the States I had read magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and others. When I returned to the continent, I started looking for magazines doing the same kind of work,” he tells me in an email. “I learnt that there were only a handful of print-based literary quarterlies being published in Africa at the time and they were challenging to get, if you weren’t in the country they were published in.”

Workman had no illusions about his model. He kept costs low and quickly decided that trying to pay writers from his own meagre purse was not sustainable. Nevertheless he kept on, and till date has published work of young African writers in 32 African countries. “I am very proud of the work I have done,” he says. Only a few can match the extensive reach of The Kalahari Review’s publishing history. Dzekashi MacViban’s Bakwa Magazine, which he founded in 2011 is notable for bringing many Cameroonian voices to limelight. Omenana Magazine, Africa’s first online speculative fiction magazine, was founded by Mazi Nwonwu and Chinelo Onwualu in 2014. “We wanted a magazine that would discover new voices in African speculative fiction,” Nwonwu tells me. “Omenana has endured because we treated it like a passion project from the get-go. Our passion endures, Omenana remains.” Like all other African literary magazine editors, Nwonwu also identifies the issue of finances as a major challenge. “Omenana is run largely out of personal pocket and it all depends on how much I could spare at any given period of time. There is also the problem of time. My day job as a journalist does not afford me enough time. There is a lot that doesn’t get done . . . there are many things I’d like to do . . . but it’s all a struggle as it is.”

Omenana has played a huge part in the acceptance of speculative fiction in Africa, discovering some of its best practitioners working today. Of these magazines, only Omenana pays its contributors, although it did not initially. The others still do not pay contributors. The Kalahari Review has a peculiarly accessible editorial model that has allowed it to endure; although one is not always sure of the value of the end result.

Perhaps if digital literary magazines such as Expound Magazine, Enkare Review, Praxis Magazine, others, which have closed shop since the 2010s have employed Kalahari’s model, the story might have been different. In July 2022, I made a Facebook post asking what happened to an important African literary magazine like Praxis, after I got blank results during a Google search (Praxis Magazine, a decade-old at that time, had gone beyond being a mere literary magazine; it was a library of contemporary African writing). I was genuinely distressed by Praxis Magazine’s sudden disappearance from the Internet space. The post generated irksome responses in some quarters, but ultimately it revealed what I had realised all along. The bottomline, then, is that African magazines are often faced with mountains of challenges with little or no support from anywhere. Most are passion projects sustained by sheer willpower.

There are some groups that have tried to mitigate these problems by forming collectives. Yet we have seen magazines such as Jalada and Enkare, which were run by collectives — and have made waves in their early days — quietly stop publishing. “The general observation in the African literary scene,” wrote Socrates Mbamalu in a profile of Troy Onyango on Open Country Magazine, “was that projects run by Collectives did not seem to last long.” I don’t know if this is the case truly, but my hope is that Agbowo, which is currently run by a collective of sorts, will not follow this tragic path.

Much further in the digital age, we are now inundated by so many more literary magazines, some catering to different literary genres and sensibilities, others with a more eclectic outlook. There is Afreada, Doek!, Isele Magazine, Afritondo, Agbowo, Olongo Africa, Lolwe, Ngiga Review, and The Shallow Tales Review, which are all making an impact in the African literary space. The Shallow Tales Review has also been organising well-regarded online literary readings since 2021. There are many others, too many to mention in one piece. What confronts these magazines are the challenges before them. In the world of literary magazines, the struggle for sustenance is an existential war of attrition, and only the most innovative and financially stable come out of it unscathed. Ukamaka Olisakwe who founded Isele Magazine in 2020 thinks that passion is both the biggest inspiration and the source of strength, but that it also acutely highlights the biggest problem facing the magazine. “We offer our contributors a very small honorarium which comes from personal funding, and this, along with the time our editors are putting in, is the reason we are here and why we will be here for a very long time. This is also frightening because the questions that pop up for me is, what happens when we are no longer able to personally fund the magazine? What changes are you ready to make? What other avenues aren’t you considering? We are, ultimately, taking this one step at a time and hope to find a permanent solution to our financial struggles.”

(Read also: Are Creative Writing MFAs the New Reality for Contemporary African Writing?)

What is the Future of African Literary Magazines?

The global problem confronting literary magazines today is the problem of funding. All other problems circle back to this. Literary magazines, it must be made clear, are not trying to follow impossible ideals of divine sustenance; they are in fact part of a brutal consumerist culture. The sooner we all realise this, the better for everyone. Magazines need to make money in order to exist. In the West, magazines are sustained by universities, art grants, subscriptions and private funding. Even with these support systems, we have seen great magazines like Glimmer Train and The Believer close down. In Africa, the problem is even more complex. Caught up in the tight financial fallout, African magazines such as The Republic are putting up paid firewalls. And one cannot blame them. African universities are not supporting literary journals. There are little or no vested institutions of state that endow the work of literary magazines. We have a rapidly disappearing middle class that is more concerned with fighting the possibility of a sudden descent into multidimensional poverty than indulging in magazine subscription. One more thing: we have an increasingly philistine culture averse to the arts.

Yet, one way of at least stretching the survival of African literary magazines is by striving towards a discreet financial economics. How this could be achieved in capital-intensive ventures like magazines remains a continuing problem. I asked Dami Ajayi this question and he replied: “If institutions like the universities do not see the need to keep a lively culture journal, or newspaper publications don’t value nurturing literary talents, or the government give folks the funding through their ministry of culture, what can we do?”

It seems that many African governments have not realised the need to fund the arts. Our ministries of cultures are mostly dormant sinecures for corrupt politicians. The death of literature and the arts is imminent if literary magazines do not devise ways to get funding. Why should we fund literary magazines though? If there is nothing else to say, much of this essay answers this question. “Literary journals are the rigorous proving grounds that early-career writers need; they are the venues that often propel us from early to mid-career,” wrote Denne Michelle Norris in an essay published in Electric Literature. “Literary journals are especially important for writers from marginalised backgrounds.”

If there is a way to convince universities and cultural ministries and intuitions in Africa to emulate their Western counterparts, then there might be hope. Some African literary magazines, like most other artistic ventures in the continent, have thrived and are still thriving on Western institutional support, which is ideal or not, depending who you ask. African literary magazines can shamelessly pursue capitalist options such as advertising and subscriptions. The irony of subscription and its elitist aspirations — especially in poor Africa — is not lost on me, but it is a price many great journals, including The New Yorker, have paid to keep existing.

Chimezie Chika’s short stories and essays have appeared in, amongst other places, The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Lagos Review, Isele Magazine, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik and Aerodrome. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture to history, art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.