One would think that with all the progress that has been made culturally, the femme fatale would have become confined to the history books. But with movies like La Femme Anjola (2021) and Ayinla (2021), it appears that she is not going anywhere…

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

Hinged on the knowledge that films reflect societal realities, films are very much shaping our understanding of reality. Films, like written or oral literature, are a reflection of the society that produces or influences. The most fictional of movies portray reality on some level. Science fiction and fantasy movies draw from and often channel very real experiences. Consciously or otherwise, movies influence our perceptions, thought processes and belief systems.

For this reason, movies have served, at various times in world history, as a tool for spreading propaganda. Before and during the Second World War, Hitler’s government used films to boost Nazi ideas among the people of Germany, manipulating viewers and instilling in them Nazi ideologies. Films were used to further communist propaganda in Stalin’s Soviet Union. And in Colonial Africa, British colonialists used film to sell images of Africans as backward and cannibalistic to its British audiences, and to convince Africans that their own oppression was justified. Till date, Hollywood films are still informing prejudicial stereotypes about Africa and Africans. And across the globe, films have and are still being used to reinforce dangerous gender stereotypes.

Contemporary Nigeria is no different. Nigeria’s film industry, Nollywood, is famous for many things, one of which is its very problematic portrayal of women. For decades, Nigerian filmmakers have utilised various sexist tropes in telling stories, from love stories to cautionary tales. One too many films have relied on the wicked stepmother, or the wicked mother-in-law, or the career woman who can never be happy without a man, or the virgin who changes the playboy, or the femme fatale, or the home wrecker. Nollywood has perpetuated these stereotypes with reckless abandon, with little to no consideration of the threat that they present to all the progress that women have made in real life.

What the Femme Fatale Trope Really Portrays

An interesting trope is the femme fatale, French for “fatal woman.” She is as old as the biblical Eve, tempting men to do the unbelievable things that they would “otherwise not do.” She is so famous that she has appeared in uncountable films noirs across space and time. Even Socrates warned men to avoid her. More often than not, she uses her sexuality to trap men. Without her, men would be wiser and unlikely to make many of the bad decisions that they unfortunately make. Or at least, that is what films will have us believe.

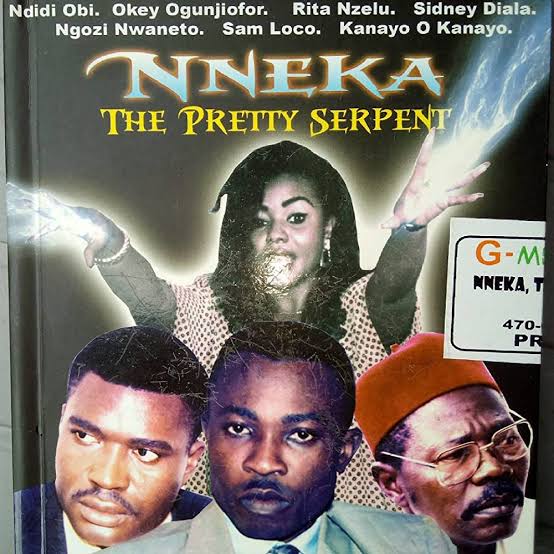

Nollywood has enough femme fatales to tell a million stories. A very memorable one is Nneka, the pretty serpent. She first appears in the 1994 horror film, Nneka the Pretty Serpent, where she uses supernatural powers (conferred on her by a marine spirit) to seduce married men so that she can take their money and souls, consequently destroying families and, in one instance, causing an entire household to be killed.

She appears again in the 2020 Play Network remake of the same title, where she goes about seducing and killing men, this time, as revenge for her mother’s death.

But Nneka is not even as famous as the legendary Karishika, the titular character sent by Lucifer himself in the 1996 horror film. Karishika’s purpose in life is to use sex to lure men, including pastors, into Lucifer’s kingdom. She takes her evil skills even further by leading women to hell with the promise of children. Her name is now the Nigerian synonym for Jezebel, and even Falz has a song titled “Karishika” in which he prays against the evil temptress. Another memorable name is Sakobi of Sakobi the Snake Girl (1998). These women were created at a time when women had just begun to own their sexuality in ways that were generally unacceptable in Nigeria’s patriarchal society. And so Nollywood, in its correctional function which it often takes very seriously, started to use its home videos to show how “destructive” it could be when women find or use their sexuality.

One would think that with all the progress that has been made culturally, the femme fatale would have become confined to the history books. But with movies like La Femme Anjola (2021) and Ayinla (2021), it appears that she is not going anywhere. Both movies are indisputably good movies, arguably two of the best Nigerian films of recent memory. But they rely on the femme fatale trope, and an argument can be made that such reliance is unnecessary. Ayinla, in particular, is a fictional portrayal of the rise to fame and the death of Ayinla Omowura, the real life Apala music legend. There are different accounts as to the cause of Ayinla’s death. Some say it had to do with a motorcycle. Others say it had to do with fraudulent accounting. But the movie inspired by Ayinla’s life goes down the femme fatale path, positioning a woman at the centre of all the bad decisions made by the man who kills and the man who is killed.

The good thing about the femme fatale trope is that the women are usually portrayed as having agency and control over their own sexuality — a portrayal that is otherwise rare, especially in Nigeria. But these films often present feminine agency and sexuality as a bad thing that never ends well for men and the society generally. What the femme fatale trope does, deliberately or not, is to blame women for their indiscretions as well as men’s. Even worse, when filmmakers attach supernatural powers to these women, the effect is to portray men as helpless people unable to exercise control or good judgment, even if they are willing. It places sole responsibility on women for actions that are taken by both women and men, or only men. And we see this blame game play out in several scenarios in real life, including situations where rapists hide under claims of indecency and seduction.

How the Home Wrecker Forgives Male Transgressions

A close relative of the femme fatale is the home wrecker. She is the woman who wrecks a marriage by, more often than not, seducing another woman’s husband. Everything goes wrong because she cheated with a married man, not because a married man cheated. Again, responsibility lies almost solely on the home wrecker for snatching a full human man, and the hurt wife of the cheating husband places the bulkiest portion of the blame on said home wrecker. Nollywood’s history is littered with films that rely on this trope, but recent examples include Chief Daddy (2018) and Tanwa Savage (2021).

In Chief Daddy, after the death of a family’s patriarch, Chief Beecroft, secret wives, mistresses and children show up at the reading of Chief’s will. In fact, one of the mistresses was known to the wife when Chief was still alive. Yet, although Chief’s wife remarks that her late husband humiliated her, she merely regards her husband’s transgressions as mistakes. The people she really takes issue with are the other mistresses. Of course, her pain is understood, but throughout the course of the movie, she does not ever truly deal with the betrayal of her husband. Instead, the movie’s script makes her focus only on the women who, in her words, “almost destroyed my home.”

Similarly, in Tanwa Savage, the betrayed wife continues to live with the husband who continues to betray her by having his pregnant mistresses live in their matrimonial home. She even fights with the other women for his attention. Her biggest quarrel is with the mistresses, and when her cheating husband realises that she also cheated and might be committing paternity fraud against him, he sends her packing without giving any consideration to his own offences. Because in the grand scheme of Nollywood things, his cheating matters less than hers and less than that of the women he cheated with. And at the end of the day, the only cheating woman of Tanwa Savage who gets a happy ending is the one who eventually births a son for the cheating man and, consequently, shares in his happy ending.

Considering this uneven sharing of responsibility, it is no surprise that in real life, many female actors have come under public backlash for being husband snatchers, with the willingly-“snatched” husbands not suffering the same level of backlash. In the same vein, male actors who cheat on their wives have been treated with a leniency that is not afforded female actors who cheat on their husbands.

The Virgin, the Playboy, and Nollywood’s Sexist Purity Culture

Nollywood’s double standard does not end with infidelity. It applies, in like manner, to purity culture. Nollywood loves its virgin-playboy pairings in romantic comedies. It is supposed to always be cute for a Casanova man to fall in love with a woman who is a virgin or who is celibate or who, at least, is “decent enough to not be easily had.”

This woman is the good woman who will reform him. It’s not that his promiscuity made him a bad person in the first place, but now, he will never look at another woman in his lifetime, because of his newly-discovered decent woman. He suddenly learns self-control and how to wait for marriage. The movie that relies on this trope will go to great lengths to show that the woman who will change the playboy is “not like other women.” As an added bonus, the movie will throw one sexually active woman into the mix and judge her for her “indecency.”

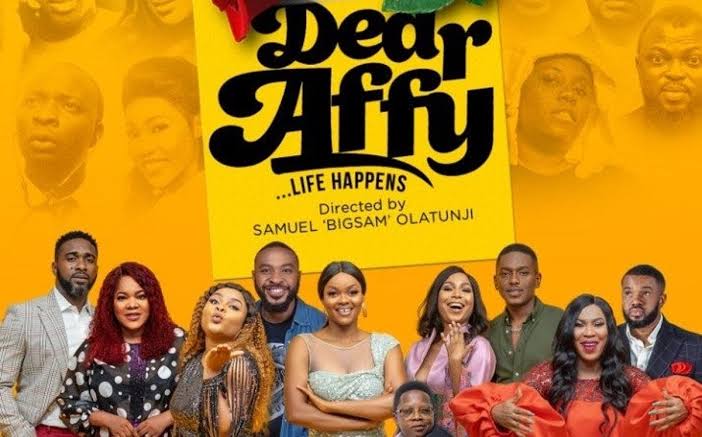

There is a long list of rom-coms that have chosen this hill to die on. To mention just a few, there is Dear Affy, which got four nominations at the recently announced 2022 Africa Magic Viewers Choice Awards (AMVCA). Dear Affy (2020) is a romantic comedy about a celibate woman who makes her Casanova boyfriend become celibate, and then suffers sexual harm in abundance, for the sake of comedy.

There is also A Naija Christmas (2021) which blesses a playboy with a Christmas gift in the form of a virgin woman who sings in the church choir and also happens to have virgin natural hair. Before these two movies, there was Gidi Blues (2016) which returned to screens in 2022 via Netflix.

Stylised as a Lagos love story, Gidi Blues pairs a playboy with a woman who won’t let him have her easily and spices it all up with a second woman who is no more promiscuous than its leading man but who gets unapologetically called a porn star by said leading man. Effectively, the promiscuous man gets rewarded with a “decent” woman while the promiscuous woman gets bashed.

Not even The Wedding Party (2016), which was released a few months after Gidi Blues and which went on to become one of Nigeria’s highest grossing movies of all time, could jump this pit. The famous couple from the blockbuster are a similar virgin-playboy pairing, and a sexually active woman is thrown into the mix and made the villain. One can only wonder why it is so important to “bless” promiscuous men with celibate women, and not vice versa. The message that this trope passes is clear: a woman is not allowed to be promiscuous, but a man can be as promiscuous as he wants without consequence, and he might even get “rewarded” with a virgin.

Nollywood Should Be Part of the Solution, Not the Problem

There are other sexist tropes that enjoy the favour of Nollywood’s filmmakers. Some of them contradict one another. For example, it is difficult to reconcile Nollywood’s perpetuation of the false stereotype that all women have natural maternal instincts with its one-dimensional portrayal of stepmothers and mothers-in-law as wicked or non-maternal. Thankfully, For Maria Ebun Pataki (2020) tramples on both stereotypes with admirable ease, and a few other films have represented women with the deserved nuances and complexities.

The truth is that because some of these stereotypes actually play out in real life, no thanks to the very sexist world in which we live, it makes sense that our movies will reflect this reality. But films, like literature, can also reshape mindsets. In a previous article, this writer noted that people who have internalised stereotypical images as portrayed in films, especially from their youth, have to interact with women as a part of daily life. These stereotypes ultimately expose women to discriminatory practices, loss of opportunities, emotional abuse and even physical violence. Nollywood is shaping the mindsets of generations and, consequently, shaping the future.

Therefore, filmmakers must develop a consciousness with respect to the portrayal of women in films, so that Nigeria’s film industry does not contribute to the marginalisation of African women, especially with the world’s growing interest in Nollywood’s content.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku, a film critic, writer and lawyer, currently writes from Uyo. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv and Instagram @_vivian.nneka