…much of the quarrel between African Americans and their brothers in Africa lies on the thin border of misunderstanding…

By Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera

Towards the end of January 2022, a section of Black Twitter caught fire when Tariq Nasheed, an African American, took to picking on African immigrants to America. It was nothing other than the familiar, “Fix your country and stop coming to our country and taking our jobs” rhetoric. Much of the discussion took place in a Twitter space, and the discussion was titled #SecureTheTribe.

Nasheed referred to African Americans as “foundational Americans” by virtue of being born in America. The Twitter space went viral and created a polarity between African Americans who were unsentimental towards Africans who sought to resist the discrimination, and argued their value as worthy immigrants who contribute to their host countries.

The argument included that they immigrated, not just as liabilities, but as doctors, nurses, teachers, tech professionals, etc., who contributed positively to the workforce.

The predominant sentiment of Africans to not being readily accepted by their “foundational American” kin is often one of shock. Africans in general, and Nigerians in particular, have always taken a holistic view of what it means to be “black” especially with regard to history, and for this reason, are single-minded in the lens with which they view colonialism and racism. But most African immigrants in their places of origin can only truly lay claim to the experience of colonialism before they immigrated.

Both experiences, racism in America, and apartheid in South Africa, have their own unique dynamics, which majorities of Africans only learn of from a few poems and maybe, novels, or in the news, themselves conspicuously distant from the remote reality. The Average African who migrates to America in search of better opportunities, often expects that by virtue of his skin colour, he should have no problems integrating with the other blacks who were born there. So, it is often a thing of rude shock, when the African immigrant to America experiences the hostilities by African Americans, or, still, other Africans in a place like South Africa.

In most cases, people can only be shocked by unexpected occurrences, or upon discovering their own ignorance. One of the biggest misconceptions among we Africans born in Africa is our belief that we are the same with African Americans because we share the same skin colour, and our oppressions are denominated by the same oppressors—the Caucasians who subjected us to colonialism and them to Jim Crow racist laws. What we Africans are yet to fully understand is our difference with African Americans, on account of our separate history and the resultant difference in our respective psychological baggage.

Skin colour, or even nationality by birth are not the only basis for kinship. Even more important is shared history and common experience, which we indigenous Africans do not share with African Americans who we parted ways with four hundred years ago. What we have not realised fully is that history is a party, and one in which you cannot join without a proper process of admission – in this case, either through lived experience or mutual understanding. An African who comes to America comes from a place where even under the whims of neocolonialism, he was able to afford the illusion that people of his kind are in charge of the affairs of his country.

For instance, the corruption, embezzlement, and ethnic bigotry which has borne down on the socioeconomic welfare of his country, is at least, a problem caused by people like him. So, he is able to at least, see himself as in charge of his own world. It is a different thing altogether from the dilemma of the African American who struggles, still even, with a system historically and racially rigged against him — and especially, the mental weight which such a system wroughts on him. Here lies the difference of a people from the same place, separated by the gulf of a 400-years history.

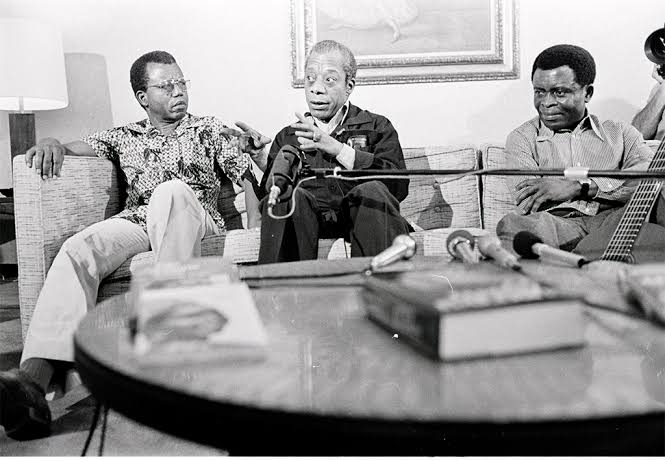

In 1980, at an annual conference of the then five-year-old African Literature Association, in Gainesville, Florida, the African American writer, James Baldwin, on seeing Chinua Achebe for the first time, lit up and called him, “My brother who I have not seen for four hundred years!” They then went ahead to have one of the most illuminating discussions by two intellectuals from the divide, although it was cut short by a disruption and verbal attack aimed at James Baldwin. Perhaps, the meeting of these two men, and the joy which presided over the moment of their meeting represents something for us.

First, being two of the most accomplished black writers intellectually, they had made great cases for their people, and were meeting, not to struggle in the system created by the white man, but to collectively push against it. They understood who they were, had read and were inspired by each other’s works and understood where they were both coming from. It was like that Igbo anecdote which Achebe had once written of, when men were called to a feast where a giant mound of fufu was placed on the table, a mound so tall that the people from one side could not see the people on the opposite side.

The two men sat opposite each other and ate, not knowing the other was there. It was when the food was half eaten that they saw each other, and shook hands over what was left of the food. Achebe and Baldwin were like these friends who had eaten enough to lower the veil which prevented them from seeing each other. Hence, the joy which greeted their meeting was the joy of the same food of history, of which they had eaten together.

This goes to show that much of the quarrel between African Americans and their brothers in Africa lies on the thin border of misunderstanding. South Africans, for instance, seem to understand racism more, and having been themselves victims of apartheid, they often share in the frustration resulting from lack of empathy from Africans, especially Nigerians.

The Zimbabwean writer, Panashe Chigumadzi, once wrote about the experience gap between Africans, and the resultant lack of empathy in her essay, “Why I am no longer talking to Nigerians about Race.” Chigumadzi, a Zimbabwean who grew up in South Africa, thought every black person was abreast with the experience until she attended the writivism festival in Uganda 2015. It was then she discovered, as she put it, “the experience gap.”

The problem with the quarrel as it is on social media is that, like most social media discussions, the aim is to stir emotions and prejudice, rather than to initiate mutual understanding capable of thinning the experience gap. African Americans try to portray Africans as people who cannot fix their countries and come over to America with a larger-than-life attitude, to take over their opportunities.

Africans, on their part, look at African Americans as embittered people who like to project their problems on the immigrants, are morally corrupt, statistically more prone to crime, and less likely to stay in school. All we see is bigotry when both parties discover they are not the same. We have not studied the sociological and psychological cause and effects resulting in these clashes.

On the flipside, there are African Americans who take deep pride in their African roots. Part of the people who bear the brunt of this quarrel are African Americans who are very keen on establishing their African ancestry through DNA tests, as to be able to be in touch with Africa. Isaiah Washington who starred as Dr. Burke in Grey’s Anatomy was so in love with Africa, that not only did he trace his roots to Sierra Leone, but also took a chieftaincy title there.

African immigrants have also experienced some cordiality in their relations with African Americans. The Nigerian critic, Ikhide Ikheloa, wrote glowingly of having had mostly good experiences with African Americans in his 40 years in America. According to him, “The tensions between indigenous African Americans and immigrant Africans have their roots in history and cultural differences.” There is distorted narrative which comes alongside these differences, which has led Africans to look on African Americans condescendingly, and the latter to look at the former suspiciously.

Ikheloa refers to a story told by Nnamdi Azikiwe in his memoir, My Oddyssey about his time as a student in America. Azikiwe, on a visit to the residence of the President of Lincoln University, found a black man gardening the lawn. Azikiwe addressed the man as “gardener” and asked him the direction of the President’s house. The gardener politely directed Azikiwe to the president’s house, and later joined Azikiwe.

It turned out that he was the President! Ikhide himself had a similar experience. While once being prepped for surgery in America, the playful man in the room whom he had mistaken for the cleaner introduced himself as the anaesthesiologist. Ikheloa emphasises how engineered narratives have led to this condescension. Narrating his story as a student in University of Oxford, Missisipi (Olemiss), in 1982, he wrote:

We [African immigrants] were given an orientation that unwittingly emphasised that we were special and different from other folks [African Americans] and we tended to walk into a room as such, as if we owned it. We were also from middle class backgrounds and had a lot more disposable dollars than indigenous African Americans. Many of us brandished our privilege like weapons and I can imagine that the resentment became a historical feud that was carried from generation to generation.

We would call them akata meaning “wild animal in the bush” and they would make fun of us coming from the jungle, etc. The disrespect was intense and mutual.

Most of our problems arise from ignorance. And the things we do not know are a result of the lack of curiosity in the average indigenous African, even among our writers and thinkers. African Americans have done more in this regard, especially in what Ikhide refers to as their relentless fight against institutionalised racism in America.

Africans, on the other hand, need to become relentless against neocolonialism which in itself is institutionalised colonialism in Africa. In relationships, true love is an offshoot of understanding. The brotherly love between African Americans and Africans could come naturally when the knowledge of our differences becomes commonplace, and is given the deserved attention instead of black discrimination. Then, we can become brothers who use their differences for common good. Most of the onus lies on Africa, the continent being the place of more suppressed curiosity. We need more people to ask these questions, to study the dynamism of this relationship and spark proper discussions which will educate us.

Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera is a writer and editor. He is the Assistant editor for Afrocritik. He contributes weekly pieces on Culture, literature and music to Afrocritik. Follow him on Twitter @ChukwuderaEdozi.