By Nzube Nlebedim

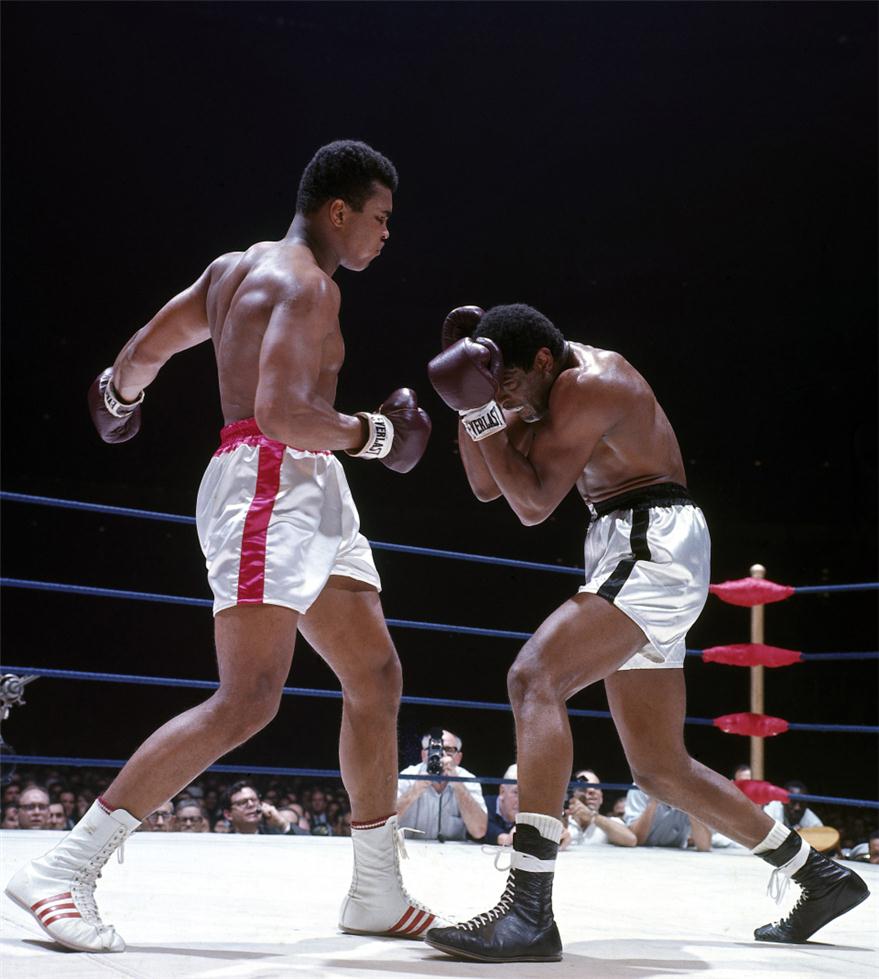

February 6, 1967, is a date in history that is most memorable for the boxing match between Ernie Terrell and Muhammad Ali. There had been a lot of buzz prior to the bout, mainly because of Ali – formerly known as Cassius Clay – who had done a rechristening three years earlier, shortly after joining the Nation of Islam.

The fight wasn’t necessarily historic because of the two fighters who were great in their own regard, but because of the public rage Terrell had stirred when he called Ali by his “slave name,” Cassius Clay. In an interview with the two fighters some days before the historic fight, Terrell (he would later admit this was an error) called Ali by his former name. Ali took this up and asked Terrell why he would call him that. Terrell, obviously not willing to apologise quickly to his large-mouthed opponent on live TV, maintained his stand and refused to call Ali by his new name. A lot of pushing and shoving ensued with Ali calling Terrell “Uncle Tom.” It was interesting to see how the bout played out: as Ali threw his punches, he would alternate his jabs with asking Terrell, “what’s my name?”

After taking interest and watching the fight over fifty years after, I knew that Ali’s inquisition wasn’t a business of celebrity, vanity nor was it an effort to show off as the World Heavyweight Champion. In her essay, “Who am I?” Hazel Rose Markus intones her argument about the inquisition into identity by writing thus:

“This deceptively simple question opens a window into how people think about themselves — the stories they tell about themselves, who they would like to be, and who they are afraid of becoming.”

It is very easy to attribute Ali’s action to mere revelry in his new status as champion of the world. On closer investigation, anyone invested in the concept of culture and identity would spot what exactly Ali’s grouse was at the time: he was a black man who needed to be addressed by his own name, on his own terms.

A black kid born in the United States of America — or anywhere else in the world divided along racial lines — is only too aware of systemic racism. Flowing from this context, the average black child knows that nothing he has belongs to him, really, and that if anything he has belongs to him in a final analysis, those things could be snatched from him by his white oppressors. The black kid who has studied history and seen how schools were segregated, or how black men were lynched for daring to be intimate with white women, knows only too well that he is not welcome in his own home.

Like Kunta Kinte who refused to accept the name “Toby”, choosing not to go by appellations assigned by oppressors is an act of revolution in itself. Ali knew the danger that accepting the name given by his oppressors would pose to his identity. Beyond the fact that he was influenced by Malcolm X, he knew that black people (at the time) were treated as slaves in their own backyard, and the least that an assertive “slave” could do was to hold on to his name, and ultimately, his identity.

What’s in a name?

It goes beyond mere identification. A name makes the man, influences his worldview, and to a great extent, his perception of himself. A name is, or at least it should be, as sacred to the man as the god he serves. What greater stamp on a man than his own identity, his own humanity?

My revolutionary soul, much like Ali’s and Malcolm’s, reverberated with passion after I read NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names. I reacted to the novel with great enthusiasm. I believe this was because days earlier, I had read Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, a novel that proved to be a radical treat. The latter tells a transgenerational and cross-geographical tale of the slave trade in Africa, with Ghana as a reference point and through the eyes of two sisters, Effia and Esi. From the sisters, we encounter a somewhat convoluted yet well-crafted narrative that crisscrosses centuries, from the bucolic Fante and Asante villages in pre-independence Ghana to the plantations in the south of America. Going through those pages, I encountered a kind of violence so raw and biting, a violence expressed in prose that functions to communicate the eternity of its buildup. Even when the young lovers in the book confront their elemental fears at the end – one dreaded fire and the other, water – the language cuts deep, and readers cannot confront a satisfactory internal denouement that they have reached the end of the story, of the suffering, racism, and hate.

Racial and ethnic divisions are two-pronged roads; each part affects the other and is affected by the other. Markus notes that “as with all identities, racial and ethnic identities are a blend of self-regard and how one perceives the regard of others“. She terms identities as “individual but also collective projects“.

I agree with these assertions. The slaves did not belong to themselves — if they did, they wouldn’t be slaves – but to their masters who owned their clothes, their bodies, their time, their minds, and the identity that came with their names. A Ness, a Sam, an Esther, a Marjorie: blacks bearing the identities of their masters. One identity is hinged to another, and none can do without the workings of the other.

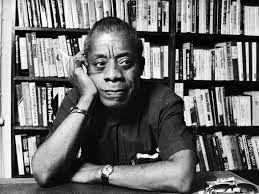

It is not very wise to assert that identity loss and cultural estrangement have nothing to do with racism. James Baldwin tells an interesting story at the end of his essay, “Dark Days.” He explains how a white student of his, at the Bowling Green State University where he lectured, asked him, “why does the white hate the nigger?” Baldwin’s shock upon hearing the question reminds me of how bitter I felt the day I discussed with a poet friend in America about the power problems in Nigeria. It was amazing to me, and I told my friend, that before we had that conversation, I had never been compelled to explain to anyone outside Nigeria how bad the power situation was. Thus, speaking about it was a cathartic experience.

When we live so long in the mud, we tend to lose a sense of our filth. Such is the experience of racism. Baldwin notes in his essay that “what my students made me realize (and I consider myself eternally in their debt) was that the notion of interracial tension hides a multitude of delusions and is, in sum, a cowardly academic formulation”.

Racism is now viewed as a worm that can’t be wholly eradicated. We have not confronted and condemned it as much as we have accepted that it is “one of those things” that make up human existence. We feel it today in the hostile stares from Caucasian attendants in cafes and shops when we move away from home. We feel it in the rejections during job applications, and sadly, we feel it at home, in our own brother’s decision to choose the least qualified “expatriate” over us.

I forgave myself of the burning anger I felt reading Gyasi’s Homegoing. Wouldn’t it have made my hurt better knowing I, an educated black man, would be treated in America and the UK with the same honour that a white, uneducated man is treated in my own homeland? Elnathan John reminds me of his statement in his satirical book Be(com)ing Nigerian, where in direct, unflinching words, he tells the expatriate working in Nigeria: “there is hardly any door you cannot walk right through and be greeted with a smile”. He continued – and this touched the very sensitive fibres of my being – “if you cannot enter, then rest assured that no one can”. How gruesome!

To understand the psychology of inequality is to understand that it is a problem of threats, a threat so subtle and sure from the oppressed to the oppressor. When I then read Bulawayo’s We Need New Names, I couldn’t have been surer I was on safe, although unsettling grounds. On these grounds, right from the start, “Hitting Budapest”, I was presented with a more metaphorical rendering of names, Bastard, Godknows and Budapest. Why the biological alienation of Bastard? Why the personal ignorance in Godknows? Why the misplaced geographic rendering of Budapest? From the get-go, we are accosted with a tongue-in-cheek displacement of identity that is too staggering and shocking to be real. For Bulawayo, identity is a crucial matter. The problem with the names is not that they are largely incorrect, but that they are culturally inaccurate. A name takes the bearer away from a circle and places them in a box. It is the same thing with class, the same with religion, the same with colour.

On my return to Lagos after my national service year, I worked at a PR firm in Lagos as an intern. For the first few days I worked there, I could never tell where the strange desire of my supervisors to put me in a box came from. The two executives who I reported to wanted me to kiss their feet so badly. I would soon understand that I had obviously been tagged, and my tag bore heavy consequences. I was never to speak against anything, I was never to contribute an opinion, I could never say no, otherwise I would be deemed “proud and overconfident”.

Oppressors and bullies of every kind act the way they do because they feel threatened. In order to win, and working on the ignorance of the oppressed, they hit first and they keep hitting until they beat down the perceived threat in the oppressed, even if the oppressed do not know why they are being treated that way.

Identity is a delicate thing, quick to slip from firm grasp. With the movement to the West, the African has lost his identity. Slowly he is becoming another man, morphing into the semblance of his massa and mistresses. Emigration is no fault of the African: we only go into the bush to hunt for deer because they cannot be found strutting on the streets. We go to seek what we cannot find at home, and in our search, we form new roots so far away from home that we cannot return whence we came. We then assume new names and take up pseudonyms to align ourselves with our new realities. When days ago, my Mauritanian boss asked that I pronounce my name, Nzube, I paused for a moment before insisting that was the name I wanted to be called. Harry would have done the trick, but Nzube meant for me something deeper than a name. Identity is indeed a delicate and fragile thing to assume, and much more deadly to lose. The extent to which Darling loses her identity is then truncated by her recourse to home in the end.

Memory, like the identity it carries, is a fragile, delicate thing. Unfortunately, memory becomes one of the ready victims when identity erodes. The characters in Bulawayo’s novel have a substantial part of their past cautered by the time that passes, the same passage of time that witnesses their loss of self. Darling realises she can no longer form any true, empathetic link with home in Paradise. Chipo, at the end of the book, senses this estrangement in Darling, even though we know Darling doesn’t know she has become somewhat distant to her own people, much like the white aid workers who came to Paradise to give them gifts as children. Paradise itself makes a blatant mockery of its inhabitants, who live in conditions that are antithetical to the name of the place. The result of this loss of identity for the black characters in the work is an ultimate and tragic inability to take hold of any culture; they are neither African nor completely American, since they can neither be absorbed into the country where they have run to seek exile nor can they show enough empathy to their own roots to be re-accepted.

Like Baldwin’s multiracial students, most of the adolescents I taught in all the colleges and private tutorials where I once worked were young children unaware of who they really are. Many, if not all, were yet to enter into that place where they denounced the burden of their colonial vestiges. But unlike Baldwin’s, my case was not racial, but linguistic in nature. The symptom of being “woke” is the ability to sound American or British. A parallel line was drawn: those who could speak English better, in an unbelievable, deliberate and bitter show of disavowal, drew the line against those who could not. Those who could not “speak so well” formed their own clique to rebel, in innocent demonstration of animosity, against their “opponents”. And so, you find that in a small classroom, there exists a clear divide that can be described as symptomatic of what exists everywhere in the world where different races meet and mix. It is not too long before the picture of the calendar and the clock surfaces: two equal objects with the same functions, but one with a much greater scope than the other; two cultures, same values, one motivated to rising, by personal and cultural factors, above the other. In the end, the seeming limitations of each of them cannot constitute the superiority of one to the other. Both are coordinated in one connecting gyre, and it takes only the humane to reconcile with.

It is admirable, then, that NoViolet Bulawayo beats the cliche scarecrow of Western and internalised African racism with a modern cane. In We Need New Names, NoViolet Bulawayo Bulawayo told us stories of forgotten identities with a biting simplicity that was too sublime, undeserving of her prose. In her novel, the sojourner is compelled to return home, the calendar stands in line with the clock. In the end, we discover the truth that the calendar is only a clock that chose ambition.

This is unquestionably the greatest essay of this year!